In the ongoing Shondaland series Head Turners, we meet interesting women from every facet of life who are crushing it in their careers. From artists and tech mavens to titans of the boardroom, these women are breaking barriers, and they’ll share how you can too.

In 2012, Briana Scurry sat in her car, tears flowing down her face, after she pawned off her first Olympic gold medal in order to make rent. The two-time Olympic gold-medalist goalkeeper for the U.S. women’s soccer team in 1996 and 2004 suffered a concussion in 2010 that brought on debilitating headaches, poor memory, and an inability to think clearly — symptoms that demanded medication and led to a deep depression. At one point, Scurry contemplated suicide.

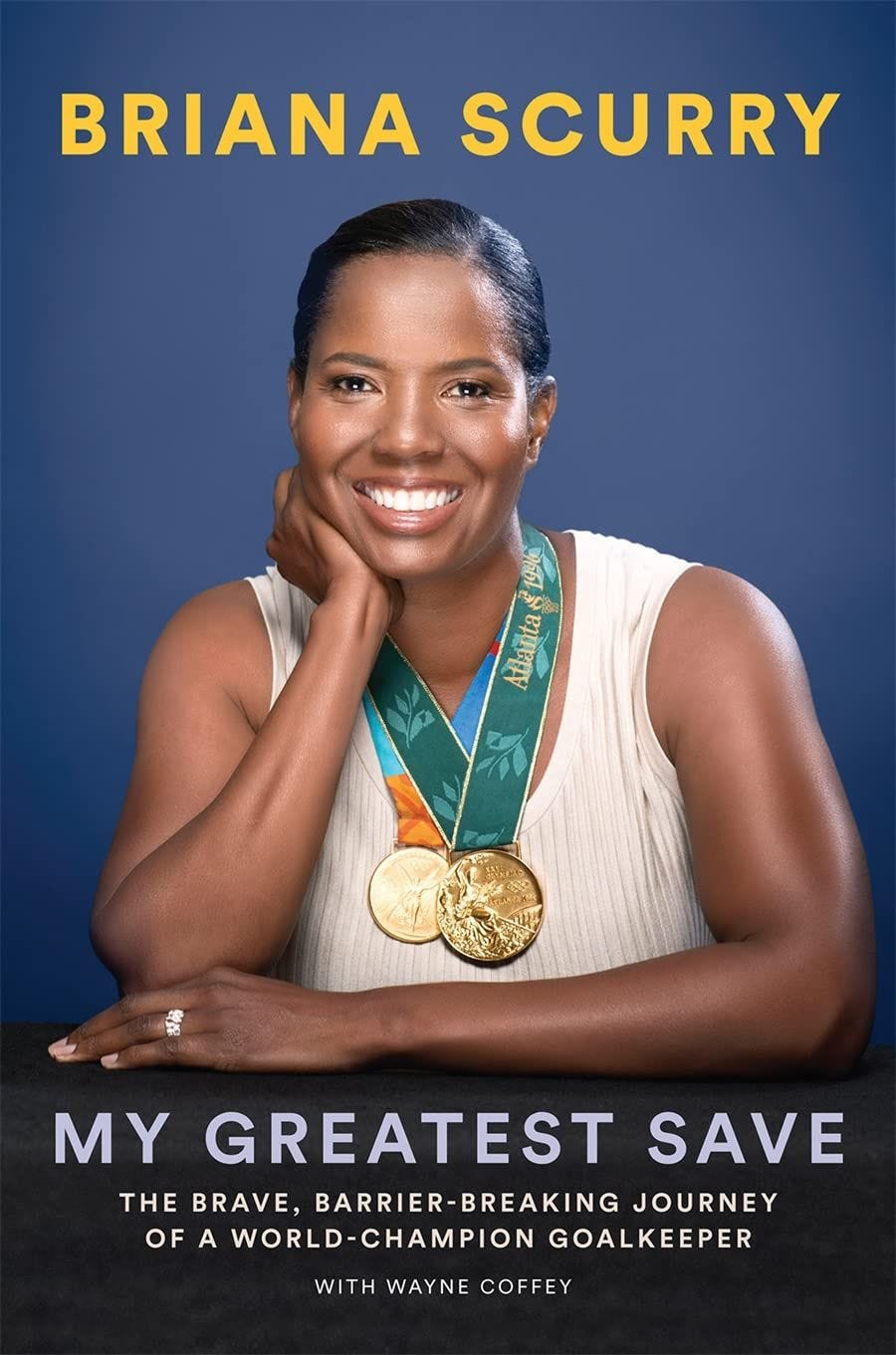

In her new memoir, My Greatest Save: The Brave, Barrier-Breaking Journey of a World Champion Goalkeeper, Scurry writes that she “felt as if I were a different person, walking around in somebody else’s body, unplugged from the rest of humanity.” Yet Scurry was able to survive and thrive. After a bilateral occipital nerve release surgery, which removed damaged tissue, she felt relief after three and a half years of constant pain.

Scurry had already made a name for herself by breaking barriers. She was the first girl on her soccer team at school, the first Black woman on the U.S. team in a starting role, and the first openly gay player on her team. In 2017, Scurry was elected to the National Soccer Hall of Fame, becoming the first woman goalkeeper and first Black woman to join the ranks.

Shondaland recently spoke with Scurry about what it was like to be openly gay on the field, the medical struggles she endured post-concussion, and how she turned herself around after the darkest moment in her life.

HOPE REESE: What do you consider your greatest save?

BRIANA SCURRY: I’m a goalkeeper, so I had a lot of them — great saves. Everybody would think that the greatest save was the ’99 World Cup. The interesting thing is, I don’t actually consider that my greatest save on the field. I consider my 2004 Olympic final as my greatest game ever. But the greatest save was, essentially, myself.

HR: You have been the first in several respects. What’s that like for you?

BS: I’ve always been the only Black kid when I played all these sports. I knew I was the only Black player on the national team that had a core role, who was a starter, basically. And I also knew I was the only out player on my team for a very, very, very long time.

I feel like I’ve noticed the only part now, more than I did at the time. I was just expressing myself, living my life in an authentic manner. It just so happened that I was the only one blazing trails for those who were like me to come behind. And making an example, especially for little Black girls, playing soccer. I did an event at a Boys & Girls Club, and one of the little girls said, “I didn’t know Black people played soccer.”

When I went home to bury my mother in 2015, I found this chest of keepsakes — a literal stack of all my pictures from when I was little into my teenage years. In every single picture, I’m the only Black girl on the team.

HR: In the book, you say that being the first in all these ways wasn’t really something you thought about at the time. Your parents and community and coaches were always supportive. Do you think it still had an impact?

BS: I think that being the only inspired me on a subconscious level. It’s hard to split the way that I just [assumed it] all the time versus the fact that I was the only — if my thought process was any different because of that. It was more about being different.

After the ’99 World Cup, I got a lot of media and press for making the save, but I didn’t feel like I got the sponsorships and the endorsements. Many people told me that they felt I got shortchanged in all of that. It wasn’t until I looked back on that. I don’t think the world was ready for a Black gay female goalkeeper in soccer, and I think that’s why I didn’t get the opportunities that I would have, considering what I did. I mean, I made a save on the greatest of stages. I just don’t think the world was ready for that in ’99. Now, it’s definitely ready for it.

HR: What about being the first openly gay player?

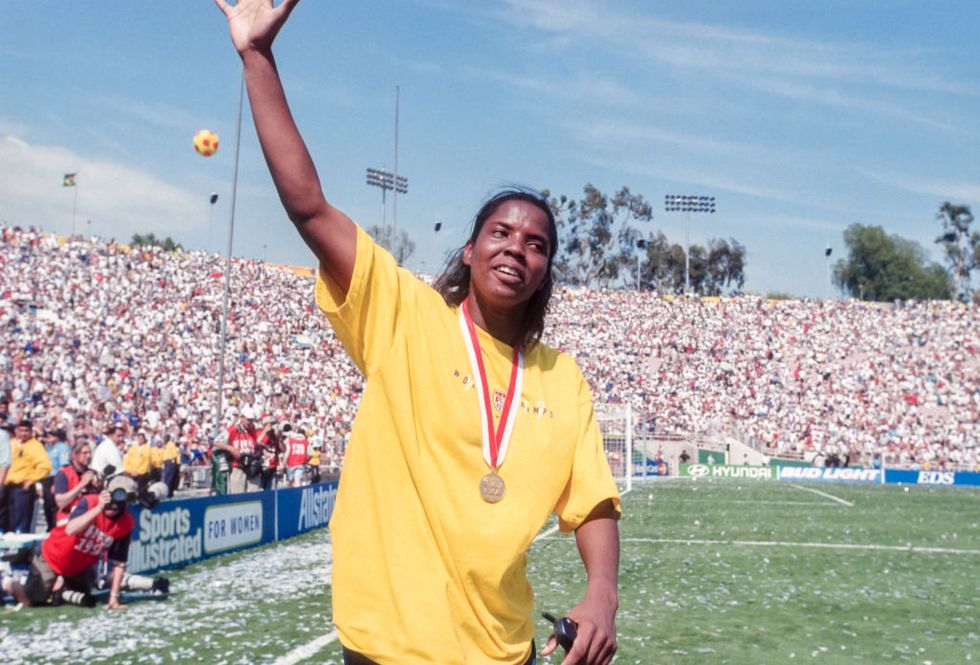

BS: In 1999, I was dating my girlfriend at the time, Brandi, and she was in residency with me. My teammates were absolutely amazing about it. At the end of the World Cup, if you go back and watch the footage, you see me run into the stands, and the camera follows me up. Then, once they realize I’m kissing a girl, the camera pans away. Later, [the camera shows] me hugging Brandi because I basically brought her down on the field, so they couldn’t get away from her then.

In 2015, there’s a great image of Abby Wambach and her partner, Sarah Huffman, kissing. It’s one of the enduring and amazing images of that 2015 World Cup. I was so proud to see how far we’ve come, where society saw her and her partner in the way that they should.

Now, with the diversity on the team and all the amazing things that advocates like Abby and myself and Megan Rapinoe are doing for people of color or for women or for gay people in the world is truly awesome. My life journey is so many different facets of the evolution of diversity in this country.

HR: You write in your book that you were bothered when questioned by a journalist about what you wanted to do after soccer. Why was that difficult?

BS: There is a bit of a taboo for an athlete to think about life after their sport. It’s almost like athletes feel they’re jinxing themselves by thinking about that. “Don’t think about that. Let’s just focus on now.” But you have to because the window is limited. No matter how good you are, you are going to retire at some point. You’re not going to play a sport until you’re 80, unless you’re playing golf, you know what I mean? There has to be an after.

I had a loose outline of a plan of what I wanted to do, but obviously, a lot more is required — study, thought process, investigating, research — because the athlete in all of us at that high level is our identity, and so you’re basically turning the page on who you are, to a degree. And that is sometimes scary.

HR: What kind of loose plan did you have?

BS: I really felt like I was an entrepreneur at heart, and so I wanted to go into some sort of business for myself, whether it was [becoming] a real estate agent and joining an agency and then maybe becoming a broker and creating my own agency. I also thought about going into finance. I thought about starting my own goalkeeping soccer training, like Tony DiCicco at SoccerPlus. Something along those lines.

The problem was that the way my career ended with my concussion, it essentially derailed all of that because I just couldn’t really think or learn. It was really hard for me [with my] comprehension and cognitive abilities. Because of the abruptness of the ending, and the fact that I had a concussion for literally three years, it really derailed everything.

I became the general manager of magicJack after that. But talk about trying to climb a mountain. Trying to understand how to construct literally every aspect of a team to put together for Dan Borislow at magicJack took everything out of me. I cried every night when I went home from work. It was horrible. I was still in soccer at least, and that’s not what I wanted. I didn’t want to stay in soccer. I had that in my mind, that I wanted to do something else unless I was doing camps, where I could build this thing. Being a GM in the front office wasn’t my idea of what I was going to do for the rest of my life at all.

HR: What happened to your health? How were you treated?

BS: The biggest challenges I was having during that time were the symptoms, the physical symptoms, like sensitivity to light. I had this headache that always emanated from behind my left ear and essentially just grew throughout the day and literally debilitated me. I was often having to take a nap just to keep the sensory overload down and to get through the day.

I was also struggling with cognitive stuff — balance — just trying to remember where things were. The sensitivity thing was really a problem because your eyes are open all day, and all the information that was coming through my eyes. It was overwhelming. Those are the physical symptoms. You add insomnia and difficulty sleeping on top of everything else — it’s a nightmare, no pun intended.

Then there’s the emotional side of it. That’s the part that a lot of people don’t talk about with a concussion. I’ve had panic attacks, anxiety, and depression. I essentially became suicidal. It was a cascading effect. It was almost like a slow train wreck of symptoms that would layer and layer on. I felt like I was sinking, and I didn’t recognize myself. It’s literally like you’re in a cave, and you’re detached from what makes you human.

HR: Why did it take so long to have your surgery?

BS: The doctors didn’t know. Part of the problem was that they wouldn’t necessarily admit that they didn’t know and say, “Hey, maybe you should go see this person.” The doctors were more like, “Okay, well, you’re fine.” And I’m like, “No, I’m not fine. I’m clearly not fine.” Or they would say, “Well, this is as good as it’s going to get.” And that’s not a diagnosis.

I instinctively knew that there was something out there that could help me, but every turn I took, these doctors were telling me, “This is it for you.” Thank goodness I had a lawyer who heard about my situation from one of my doctors. He said, “This is going to take a long time. We have to find the right doctor for you, and somebody has to pay for this because this is not your fault.”

That’s why it was so long: the court entanglement and the workers’ comp part of it because their philosophy is deny, deny, deny when it comes to insurance companies and workers’ comp. We had to go to the courts six times. I probably could have gotten help in maybe two years as opposed to three if they had just allowed me to seek the care I needed and stopped trying to put up obstacles everywhere I went.

HR: There was a time when you were struggling to make rent. You even pawned off your first medal. Looking back, is there any advice you would have given yourself about finances?

BS: I knew if I pawned my medal, and that was the only thing I had of value, that I could at least have some breathing room. And that’s what I did. If I were a male that had won an Olympic gold medal twice and a World Cup in soccer once, I would never have been in the financial situation I was in. It just wouldn’t have happened because I would’ve been a multimillionaire many times over. And that’s the truth. But I didn’t think of it that way at the time. I have wanted to be an Olympian since I was 8 years old. I always looked at it with the eyes of an 8-year-old. The glory and the joy and the spectacle of it and the amazing experience of it.

HR: How did you turn your life around?

BS: The first element was the visual of my mom being told that I had killed myself. I couldn’t bear the thought of it, so that initially turned me away. Shortly after that, my angel Naomi Gonzalez and her partner, Fran, started a Kickstarter campaign, which was a great success. My future wife, Chryssa, saw it. She invested, and then they met, and Naomi told her about me.

Once that happened, that was my lifeline right there. I had hope again. Here’s the interesting thing about depression and being suicidal. I was close to getting out of the hole at that time, but I couldn’t see it. A day was so long. I mean, if my mom had not been alive at the time, you and I wouldn’t be talking.

My amazing wife, Chryssa, came into my life at a time when my mom was exiting it in late 2013. My mom passed in early 2015, so roughly a little over a year. And she got me out of the hole enough that I never went back into that space again. Love was the answer. Love was what got me turned around.

Hope Reese is a freelance journalist who has contributed to The New York Times, Vox, and The Atlantic. Follow her on Twitter @hope_reese.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY