If you have kids (or know anyone who does), you’ve undoubtedly borne witness to the compulsion to be the perfect parent — whatever that is. Once you become a mother, the pressure to do the job without fail comes at you from all angles: ourselves, others, social media, TV, film, medical experts, the list goes on ad infinitum. But ultimately, the joke is on us. As much as we love our children, perfect parenting is a ruse; we’re all human, and there is no such thing as perfection. Yet the aspirational messaging involved in this facade is woven deeply into the fabric of American society while our policies — or glaring lack thereof in too many cases — systemically set us up to struggle throughout the experience.

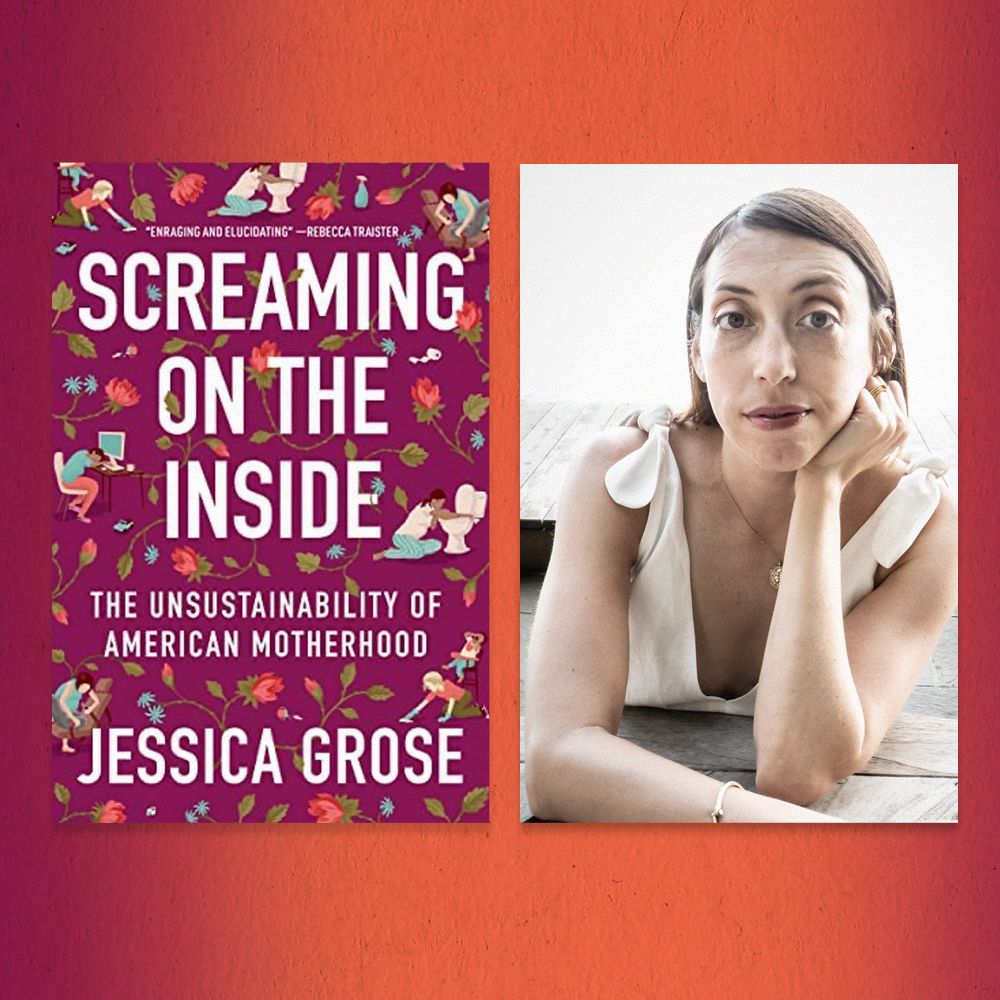

For the past decade, New York Times opinion writer Jessica Grose has devoted her career to exposing the trials and tribulations involved in parenting as an American, and the myriad systemic failures that begin with inequities in women’s health care during pregnancy and birth, a lack of paid parental leave, a lack of available subsidized child care, and all the way to the insanely exorbitant costs involved in sending a kid to college. These issues have always made child-rearing difficult, but the pandemic did a spectacular job of making even the privileged aware of how many ways mothers are forced to choose between earning a living and caring for their children.

Grose’s new book, Screaming on the Inside: The Unsustainability of American Motherhood, is a deep dive into these issues and many more, following the trajectory of American motherhood from the ridiculous approach to prenatal care in the 17th, 18th, 19th, and, frankly, 20th centuries to how her own prenatal health issues forced her to choose between work and her baby. She goes further into the pandemic and all of its glorious horrors while also highlighting the activists who are working to improve our experience every day.

Grose — who has also authored two novels, 2012's Sad Desk Salad and 2016's Soulmates —recently spoke with Shondaland about what went into writing the book, the most surprising things she learned in her research, and what she learned in speaking to so many women about their experiences with motherhood.

VIVIAN MANNING-SCHAFFEL: Screaming on the Inside is such a great title. As the mother of two older teenagers who has been financially forced into freelancing for almost 20 years, I can relate. Was the title an intuitive choice for you?

JESSICA GROSE: We went through a number of titles, and my agent, Elisabeth Weed, who was amazing, that was her idea. When she said it, it just felt immediately right because it wasn’t just talking about moms during the pandemic. It was also this idea that mothers have forever been talking about how difficult it is to be a mother, if only with other mothers, their friends, their sisters, and their mothers. They just weren’t listened to — because nobody listens to women — so I wanted to sort of wink at that, reaching back forever at this line of mothers who were probably speaking honestly about their difficulties, but it wasn’t acceptable to tell the truth about the good and the bad of motherhood. So, the title is sort of referencing that as well. There has been, and even remains, a lot of pushback when you try to express anything about motherhood that isn’t all sunshine and puppies.

VMS: I was fascinated with the early chapter where you set up the premise and do all this hardcore reporting about the perceptions and realities of motherhood in the past. What was the most surprising thing that you learned in doing all that research?

JG: How long it took people to really understand how babies are made, and how that was used against women for eons. The modern notion of how babies are made is basically 100 or 150 years old. I had done some reporting for a special fertility issue of the Times the year before I started the book, so I kind of knew a little bit about it, but it wasn’t until I deeply reported that I was like, “Wow, nobody knew anything about women’s bodies, and what they did know was hilariously incorrect.” It always makes me laugh to think about maternal impressions, which is this idea that if you were pregnant and you looked at something, it could have an effect on the baby. If you looked at a frog at the wrong time in the wrong mood, your baby would look like a frog. That’s ridiculous, but people really thought that for like 1,000 years.

VMS: I couldn’t even believe it! You cover parenting for The New York Times — is that what led to you turning all this research into a book?

JG: I mean, I’ve been thinking about these ideas, I’ve maybe even had inklings of them, before I even got pregnant for the first time and certainly since I had a really difficult pregnancy with my older daughter, which I talk about in the book. I had hyperemesis gravidarum, which is extreme vomiting. I got really depressed, and I had to quit a job that I was really excited about because I was so sick. I knew intellectually, even before I became a mother, that the systems around parenting in the United States were terrible. Then, having experienced all of the holes in the safety net for myself — and having it be so dramatic despite having basically every privilege you could possibly have in the United States — I just really made all of these issues part of my work life forever. Since I went through them, I was just like, “People need to know, they need to be aware, they need to know what they’re getting into.” Really, the pandemic crystallized it because it became more clear to the rest of American society who probably wasn’t paying attention how much more difficult we were making parenting than it had to be.

VMS: You pull in your own experience, your own thoughts, and your own comments as the book progresses. It’s kind of like your friend is sharing information with you. Was it at all challenging or cathartic in any way to reveal bits of your own life, especially such vulnerable bits of your own life?

JG: Writing about my first pregnancy, which was so painful and scary, and having to put myself back in the mindset of that time, was tough. I wanted it to feel really visceral for the reader. I wanted it to feel like you were slightly living through it too, almost like I wanted it to sound like a horror movie.

VMS: It kind of did!

JG: [Laughs] I wanted the reader to be there with me, and so I had to put myself back there to an extent, and that was hard. It was hard and un-fun. Writing the chapter about the sort of the three to six months of the pandemic … I wrote so much of this book with children screaming downstairs. It’s actually remarkable. Don’t ask me how I did that — dissociation, I guess.

VMS: Like we all do — you just hide in a closet, right?

JG: Exactly! Writing about those first couple months of the pandemic, especially when my parents had Covid in March 2020, and I was like, “Oh, are you going to die? Everyone seems to be dying! This is bad!” Reliving that was also not great. For the kind of book I wanted it to be, I wanted to make clear I had experienced at least some portions of what the other moms that I talked to for the book were experiencing so I could sort of empathize and relate and act almost as the reader’s guide as they hopefully empathize and relate to the 100 moms I spoke to. I don’t know if it was cathartic. I can’t tell yet. We’ll see. I’m definitely nervous about it, only because every time I write about prenatal depression, people will say people with mental illness should not be allowed to be parents. That’s just an ignorant and dumb thing to say, especially because 20 percent of moms have either prenatal or postpartum depression. So, you’re saying a fifth of the population should not parent? You don’t know before you’re pregnant if you are going to be someone who has a mood disorder. So, I’m bracing myself for that sort of feedback, but it’s what it is. I have feelings, but I think it’s worthwhile because I want to normalize these experiences and destigmatize them.

VMS: As someone who just reports about other people’s lives, it can be terrifying when you put out an essay, which is a piece of yourself in your work, because typically you’re the observer. In your book, I think you’re conscious about taking a fair and equitable approach by talking to women from all kinds of different backgrounds about their parenting experiences. What was the most surprising thing you took with you about someone else’s parenting experience?

JG: Thank you for noticing that. I definitely did my best to talk to as many different kinds of moms as possible, but I also want to make clear there are as many different stories as there are moms. There are 100 million moms in the United States alone. There are so many stories that I couldn’t get to, and so many stories I couldn’t include — not because they weren’t important and special, and I’m so grateful that they would talk to me — they just didn’t fit into the construction of the book. One thing that was surprising was how uniform the pressure was that people felt in terms of which ideals they weren’t living up to. That was surprising. Obviously, I traced the history of them, but most everybody I talked to was savvy and understood that these were mostly BS ideals, and yet they were completely seduced by them anyway. The uniformity of these ideals — we all agree on what they are, and most of us think they’re dumb, yet we still feel guilty for not reaching them. They felt this sort of Donna Reed pressure to be a perfect mom, to never act like motherhood was unpleasant for them, and to do all the domestic tasks expected of women for eons — those things die really hard. Even when women were the primary breadwinners for their families, I think they felt very obligated to do these things, even if no one in their life expected them to do all these things. They still understood that the pressures out there existed, and they were defining themselves against those pressures. Does that make sense?

VMS: Absolutely. It’s interesting that it’s so deeply woven into our culture.

JG: Exactly, and what the ideals were — there was sort of a shared idea of that. I don’t even know if they could articulate exactly what they were; let’s just call it a vibe.

VMS: I appreciated it when you got into blogger culture, which was the precursor of influencer culture, then talked about the uniformity of the people who tend to do these things and how much of the social media portrayal of parenting can be bulls--t. Yet, this compare-and-despair tendency has a profound impact on people. Is it possible that this Donna Reed mentality you speak of will ever dissipate from our culture? Can’t we just see ourselves as people who happen to be parents? Are we ever gonna stop trying to be the perfect parent?

JG: I sure hope so! I think it will always be around in some form. It’s too powerful to die, and there’s too many people invested in it. I can only speak for myself, but my children are the most important thing in my life. I love them to the end of the Earth. If you mess with them, RIP you. I will fight for them. I think that’s primal — a lot of people feel that. Wanting to do the best by your kids will never go away. But having a more realistic idea of what that means, and learning to apply your own values and not someone else’s values, that’s sort of like the whole project of parenting. Does that make sense?

VMS: Totally. What was the most challenging chapter for you to write in terms of your own emotional investment in the topic?

JG: Obviously, the pregnancy chapter was really hard to write as it was sad. It was wrenching.

VMS: The pandemic chapter really exposed the realities of parenting during the pandemic, which was basically a nightmare for every single one of us — whatever age your kids were, we were all hosed. Do you hope that exposing the inequities might somehow lead to positive change? Now that the book is coming out [on December 6], what is your biggest hope for it?

JG: I mean, the biggest thing that needs to happen is political change. Parents just need money. They can’t afford childcare. People are not having their ideal number of children because they can’t afford to. Whether it’s money sent directly to them, the way it was last year with the increased child tax credit; whether it is a policy that makes payment to childcare workers greater; whether it is finally getting paid leave … I will say that there were two states that passed paid leave as I was editing the book. So, it went from like 12 states to 14 states, and that’s just in a year. Even though there is sclerosis on the federal level — I’m not very optimistic on anything happening at the federal level for the next two years. But you just never know. Sometimes, good policy comes from unexpected places. Policy-wise, any incremental move forward is a small win. There’s so much need to get us up to where every other country that is as wealthy as the United States is.

I am most optimistic about paid leave because it’s something that everyone wants. I just ran a piece this weekend where I talked to a pollster who mostly polled Republicans, and she said men who live in rural communities are really adamant about wanting paid leave. Let’s say their wife had a C-section. They need extra help, but they work an hourly job and have zero paid leave. They are trapped, and they’re far from any services. There is a complete shortage of caregivers in rural America, so they really want paid leave. The idea that this is just a mom thing or a liberal thing is, frankly, not correct. Anyone who says they are interested in American families and “family values,” how can you not be moved by that? It’s very straightforward and very logical.

VMS: My last question is a two-parter: You’ve previously written two novels. Do you think you’ll go back to fiction at some point? And what do you think you’ll work on next?

JG: I don’t know that I will ever write another novel. I have no ideas! If I ever have another idea for a novel, I would be interested in doing it, but my brain doesn’t seem to work in that way. I really want to concentrate on my day job for now. Promoting this book will be great, then maybe doing some more speaking to talk about all these issues. But mostly, I’m looking forward to going back to having one job instead of six!

Vivian Manning-Schaffel is a multifaceted storyteller whose work has been featured in The Cut, NBC News Better, Time Out New York, Medium, and The Week. Follow her on Twitter @soapboxdirty.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY