After making the hour-long drive from Los Angeles to Irvine, California, I don’t even have to ring the bell. I slip open the door, take off my shoes, and climb the carpeted stairs. At the top, I’m greeted by an assortment of small dogs seeking attention. In the kitchen, the island is already overflowing with homemade staples like mac and cheese, dinner rolls, and sweet potato casserole. There are also unique dishes like a pot roast glistening with soy and sake, Vietnamese egg rolls, and a basket of fried chicken.

In the living room, a Clippers game is playing on the TV next to a Christmas tree decked out with ornaments added by the guests, such as a Steph Curry bobblehead from a Bay Area pal and one that resembles a fish stick. (It’s a joke directed at the host, who doesn’t eat fish.) A glass of Scotch is thrust into my hand. I ease onto the wraparound couch, and there’s immediately a dog on my lap. I exhale. I’m at Friendsgiving — and it means everything.

I’m a transplant to Los Angeles, a place notorious in its sprawl and challenge in finding a sense of community. I’m single. Despite my adventurous, independent streak, somewhere inside me is a deep-seated neurosis about feeling like I’m on the outside with a longing to feel included. I think it goes back to childhood growing up in Cleveland. I love my parents, but they could hardly be described as the warm type. And one of my earliest memories is of my brother and elementary school classmates taking my coat, pushing me in a snowbank, then locking me out of the house.

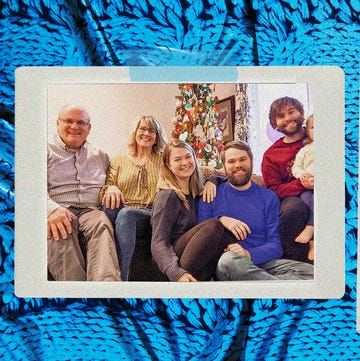

There’s no snow here, only powdered sugar dusted over letter-shaped brownies that spell out F-R-I-E-N-D-S. Richard is the host, but Patty is the organizer and ringleader. She’s the one who, weeks in advance, is sending out the Doodle to pick a date. She coordinates the expansive menu. And she’s the one collecting the friends.

I first met Patty more than a decade ago in my first year of teaching. We shared an adjoining door and students. When they were with her for math and science classes, they sat down and learned. With me for their English and history lessons, they wandered around and threw crumpled-up paper at one another.

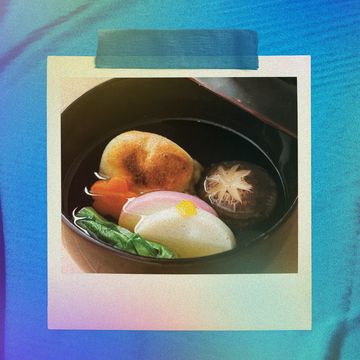

Patty tried to help me during one-on-one mentoring sessions, but she broke out in hives because my classroom was so dusty. We moved our planning sessions off campus. Over a bowl of ramen or mango sticky rice that she introduced to me, we found a shared set of values and gradually became a professional team. Two years later, when a new school opened down the street, we transferred together. And five years after that, once Patty had become a district administrator, she introduced me to the principal of the school where I still teach today.

What began as a professional relationship grew into the most meaningful friendship of my life. Ever the coach, Patty taught me how to wrap bulgogi in a lettuce leaf and crack the egg over a hot pot. She supported my crazy ideas, like when I promised the kids on the running team I coach that we’d go run a race in San Francisco. She encouraged me to write even though she originally said she didn’t understand the impulse. After I went through a bad breakup, she let me live for a month in a spare bedroom at her and her husband’s house in Long Beach, reminding me of a valuable lesson: I was enough.

I’m far from the only stray whom Patty brought into her clan. Over the years, her guest list for weeknight dinners, Scotch nights, Vegas trips, and eventually Friendsgivings grew to include chums from across her life. All were welcomed as equals around the table as long as they were kind, funny, and shared her passion for tasting all the desserts.

Patty continued to grow her friend circle while living with breast cancer. She was first diagnosed in 2011. It returned in 2014. She passed away in 2019, just before the start of the pandemic. For those eight years, she kept planning food tours and organizing trips for us to Chicago and New Orleans. She continued to give me good advice even when I didn’t want to hear it. She went ice climbing and became an advocate for metastatic cancer research, and she took on new roles at work.

The pandemic and Patty’s death scattered the friend circle she built. We worked from home in bedrooms and on kitchen tables. Some of us stayed close by in L.A. Others worked remotely from distant parts of the country. We kept to the tight bubbles of housemates or immediate family. When we began to emerge from them, haltingly trying to reconnect with others, I thought of Patty. We all did.

Slowly, guided by Patty’s example, we’re beginning to come together again, learning to take the initiative, send that email or text, schedule those dates on the calendar. This summer, Jason, Patty’s husband, organized a backyard potluck. He plucked figs from the trees he tends to and grilled fish that he caught. Richard, his best friend from college, organized a day trip to Catalina Island. We went parasailing, a first for me. Alongside Jason, I shared a perch in the sky.

This year, we’re planning to gather again for Friendsgiving. We’ll likely go visit Patty in the morning at Rose Hills Memorial Park. Later, a turkey will be deep fried on the driveway. Someone will bring eggnog from Broguiere’s Dairy, which we’ll drink crowded around the kitchen island as dishes come out of the oven. Then, we’ll serve ourselves buffet style. Instead of baking, we’ll pick up the pies. There will be wine and interactive party games on the TV, where we’ll try to stump one another with deliberately false answers to trivia questions, seeing how well we still know one another after all the time apart.

And we’ll fill up a plate for Patty and place it in front of an empty seat saved for her. We’ll tell her we love her and thank her for bringing us all together that first time — and for bringing us together once again.

Carl Finer is a Los Angeles-based teacher and writer who has contributed to Runner’s World, Zócalo Public Square, Chalkbeat, The Imprint, Belt Magazine, and Education Week.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY