We need beauty — it lifts our spirits, revitalizes our imaginations, and soothes us. Beauty, both internal and external, can be a healing force in our lives, so we’re bringing you a series of stories that examine the ever-changing role of beauty — in our personal lives and in society, and how this impacts us individually and collectively.

Sithy Bin was a 24-year-old member of the Crips With Attitude gang on September 2, 2005 — the day he drove to the home of a rival gang member, pulled out a 9mm gun, and fired at people in the front yard. Growing up in Modesto, California, a farming-rich city of about 200,000 about 90 minutes east of San Francisco, Bin, the son of Cambodian immigrants, was indoctrinated into gang culture as a youth, but when he showed up to fire at a rival’s house, he hadn’t intended to kill anyone. “I didn’t want to hit them. I wanted to put holes in their car, the house.”

That, unfortunately, isn’t what happened. He didn’t know it then, but Bin’s shots critically wounded a 39-year-old mom who was in the wrong place at the wrong time. She wasn’t in a gang or affiliated with one; she was just hanging out at a barbeque. Thankfully, she survived, but the following day Bin was arrested. He was sentenced to 40 years to life.

More on Beauty

“I was devastated,” he tells Shondaland. “It was heartbreaking. It was an ‘aha’ moment. That could’ve been my mom, my auntie. It could have been you. Thank God nobody died. I had been so self-centered. It made me change my life.”

In prison, Bin participated in several programs and workshops — anything he could do to improve himself — even becoming part of a church-ministry program. Officials were so impressed with his reformation, they took 25 years off his sentence. He was released in 2018, 15 years after he was first incarcerated. Part of his release, however, included a stay in transitional housing, and it was there that he participated in one more program — the program that he credits with bringing some beauty to an otherwise dark period of his life. Called “Give a Beat,” the six-week course taught him the basics of deejaying and music production, giving him and his classmates a chance to use creativity that had been stifled or nonexistent in those bleak days behind bars.

“It was gloomy,” says Bin. “There was no hope. The only time there’s light or a ray of hope is when [we get to participate] in these programs or workshops. The volunteers are amazing. It’s the only time we are treated as human beings.”

Beauty, of course, can come in various forms — in things people throw away, things others see as grotesque, and sometimes the unlikeliest places. You don’t have to have been locked up to surmise just how unbeautiful prison can be — you’ve seen enough on TV to have an inkling — which is why programs like Give a Beat, part of a wider initiative to bring art into prisons, is nothing short of revolutionary. Transformative Arts, part of the California Arts Council’s state-funded initiative to enrich the lives of citizens through the arts, works in partnership with the California Department of Corrections to offer theater, dance, journalism, Native American beadwork, and, yes, music to people experiencing incarceration. (Administrators prefer “people experiencing incarceration” over the less humanistic term “inmates.”) Give a Beat is one of Transformative Arts’ most popular programs.

“It is always incredible to meet participants and hear their stories, to see the impact the arts have,” says Mariana Moscoso, program manager for Transformative Arts. “The most beautiful thing I see is the enthusiasm of participants, how proud they are of their work. It shows how art is a tool for liberation.”

Transformative Arts started in 1977 as the Prison Arts Project, signed into law by then-Governor Jerry Brown. Funding came from a variety of sources including the National Endowment for the Arts, California Arts Council, and the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, but by 2003 a state budget crisis reduced the program’s size, and by 2010 the program had ended entirely. Efforts to revive it began around 2013, and by 2017 arts programming was back in all 35 of California’s state prisons. The exact number of participants fluctuates, and facility visits have obviously been impacted by Covid. But, through its work, Transformative Arts has enlisted lots of groups to bring their workshops and courses to people who desperately need to have their humanity recognized, for someone to see them as a person with a voice, a story, and talents. Give a Beat offers a prison electronic-music program, as well as a reentry-and-mentoring program (among others), with a multi-week curriculum that teaches hands-on learning of software and equipment, business development for careers in music, and a breakdown of how music can be a tool to shift energy and resolve conflict. Part of the course Bin took included breathing exercises and other tools to actually feel like an artist.

“The talent [among the] incarcerated is unbelievable,” says Todd Strong, the program director and a teaching artist at Give a Beat. Founded in 2014 by Lauren Segal, Give a Beat was created specifically to help mitigate what the group calls the “enormous domestic injustice of incarceration,” and now selects 12 to 16 students for six-week, four-hour classes. They provide them with everything the beginners need — laptops, software, headphones, the whole nine yards. “After an hour or two, they’re like, ‘I’m not in prison anymore.’ They’re like, ‘Wow, this is beautiful.’ You see smiles. They change from having to deal with all the drama of prison life. It reduces violence, gives hope. It just fills people’s hearts,” Strong says. He recalls one 66 year old who’d been part of a breakdancing crew in the ’80s. In one session, he started popping and locking, feeling free for the first time in decades. “He might as well have been 24. Just getting down — he was so vulnerable. And, on the last day, he was just crying these tears of joy, saying how much love he felt. It goes on and on like that.”

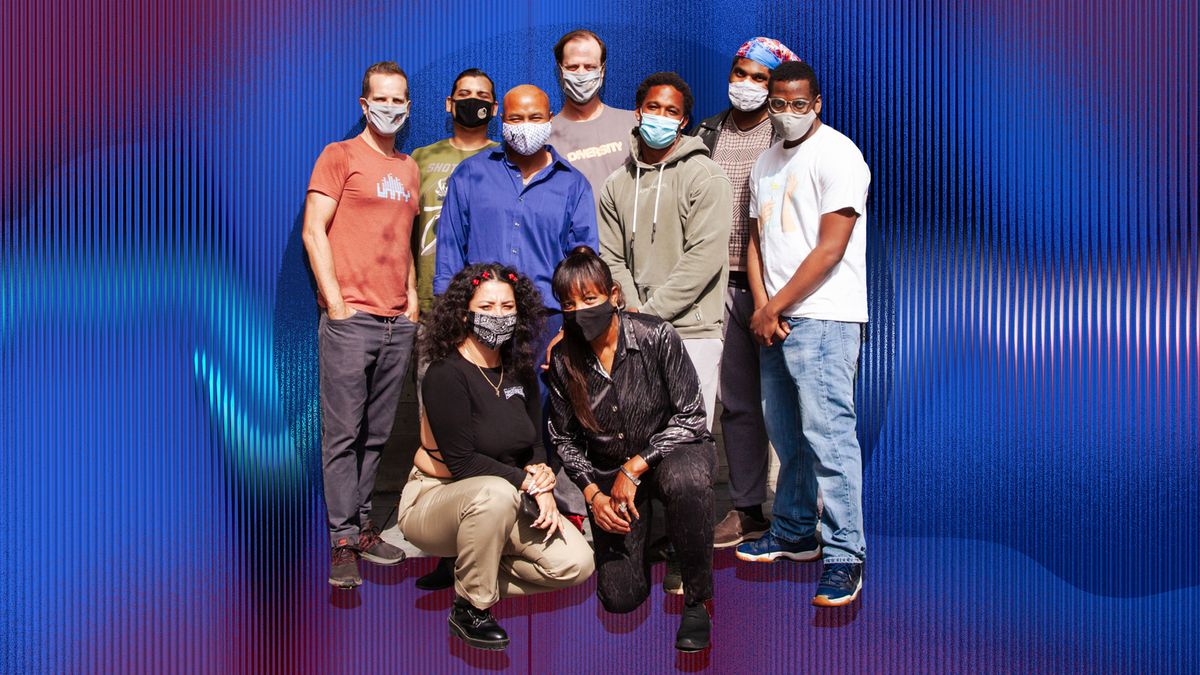

Upon completion, participants get a certificate and even a graduation ceremony where they get to perform for loved ones. Give a Beat just graduated a new class in early May — a cadre of inductees who’d been newly released and participated in the course under strict Covid protocols.

Geri Meyers, 60, is one of the folks who performed a set alongside her classmates at the ceremony in downtown L.A. As it happens, she’d long dreamed of making music; as a full-time aerobics instructor before her arrest, she always envisioned herself making beats to accompany her high-energy routines. “My whole set, people were dancing, moving,” she says. “I was told people didn’t want to go after me because my set was too high energy! Give a Beat let me know I can accomplish anything I set my mind to as long as I’m focused and determined, whether I know how to do it or not.”

She killed her boyfriend when she was 45. “That was my only crime. I didn’t even have a traffic ticket.”

He’d pushed her to the ground, choked her, and spit on her for years. It came to a head one last time. “When I asked him why he treated me so bad, he said, ‘I’ll show you what being treated bad looks like.’”

Meyers knew what was about to happen next. He did not. “I [decided] that day I wasn’t going to run, to be afraid anymore. I shot him.”

He died instantly, and Meyers spent the next 15 years in prison. She studied domestic violence to understand why she stayed in the relationship, and worked to counsel other women about domestic abuse. She taught fitness and wellness too. Governor Jerry Brown cut her sentence to 15 years, citing her “significant transformation,” and she got out in 2018. She’s now in transitional housing as she rebuilds her life and career; in mid-May, she got her Give a Beat certificate and is now slowly building a library of mixes designed to complement fitness routines.

“Give a Beat gave me an opportunity to pursue a dream. In spite of me being a felon, in spite of my age, they opened that door and believed in me. There’s so much beauty in that.”

Malcolm Venable is a staff writer at Shondaland.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY