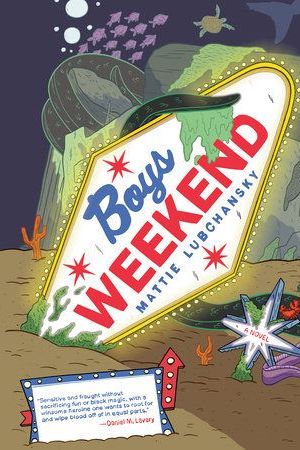

Mattie Lubchansky’s newest graphic novel, Boys Weekend, is a mix of satirical humor, poignant reflection, horror tropes, and an anti-capitalist spirit that graces most of their work. Lubchansky is the author and co-author of multiple books, including 2016’s Dad Magazine with Jaya Saxena. They are also an associate editor and contributor to The Nib, a soon-to-be-shuttered beacon for all sorts of writing and comics, both online and in print.

The premise of Boys Weekend is loosely autobiographical: Nonbinary protagonist Sammie agrees to be the “best man” at their college friend’s wedding and is invited to the preceding bachelor party-esque weekend in a fictional Vegas-like city built on an island of trash in the ocean, which evokes a Westworld playground where people can indulge in their worst and strangest hedonistic fantasies, including partying in a submarine on the ocean floor and hunting AI versions of their own clones. The book follows Sammie as they navigate their loyalty to this friend, the ways that their life has changed, and their relationship with self, all against a backdrop of cultish MLMs, literal and figurative monsters, toxicity of all kinds, and some scary sea creatures. It’s a romp of a book that is also tender in all the right places.

Shondaland spoke with Lubchansky about the unique friendships amongst the queer community, letting go of your past life, and more.

SARAH NEILSON: Was there any initial seed or spark that led to this story?

MATTIE LUBCHANSKY: I was at a friend’s bachelor party in Las Vegas, maybe three months after I came out. And I was already going to the bachelor party when I came out; I had already agreed to be the best man for this wedding when I had come out. ... My situation is a lot different from Sammie’s — I like these friends; I’m still friends with them. It was like a very muted and pleasant version of the book happened to me. While I was there, I was having an idea about how I went through the process of being my friend’s best man while I was in the middle of coming out to my family and all this other stuff. And to my friend’s credit, he asked me, “We can think of a new name for the program?” It was a much more supportive experience environment with a good friend of mine, but I was thinking about the nightmare version of what happened to me and then just kept making it more of a nightmare the more I thought about it.

SN: Can you elaborate on the setting and the world-building of the book? How did you come up with the idea to make it like this garbage patch-style destination island? And how did you go about playing into or playing up the absurdity of capitalism and toxic masculinity and bro culture with the setting and the world-building?

ML: The setting of the book is called El Campo, which is a sort of libertarian Las Vegas in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean that’s sort of like an “anything goes paradise” for mostly the rich, but also your aspirational, not-yet-rich kinds of people. Las Vegas to me is … I don’t like it there. I have a bad time when I’m there. There’s something about the idea of an “anything goes” environment that’s very prescriptive in terms of what “anything” means. It’s anything goes as long as it is cis het in a way — which is not to say there is not queer life in Las Vegas; I’m sure there is for locals. And I’m sure even for tourists there’s the odd Pride thing or whatever, but it is an environment in which you’re expected to be a certain way. So, the idea of a place that is for people to enact their wildest fantasies, but not those [people], was interesting to me. And then in terms of fitting in with the culture … capitalism’s the same kind of prison that masculinity is, it is something we’re all doing to ourselves, it doesn’t have to be this way, society doesn’t have to work this way, a lot of men aren’t like this. It’s all like self-oppression on some level. To me, it’s all very intertwined — capitalism, gender, and societal expectations for how we’re supposed to interact with each other [are] often enforced punitively and often violently. It’s all one big morass of the s--t we do to ourselves. It was interesting to me.

SN: Can you talk about the contrast between the old friend group and Sammie’s new friend group and their new life, and what was important for you to convey about that difference?

ML: That was something that came later to me when I was working on the book, this idea that their life back home was good. Again, this is something that Sammie did not have to be doing. It was something they chose to do out of some bizarre sense of loyalty. And I think it was important to me to have that baseline of this good queer life with people that understood them and respected them and supported them. Not blindly, but just people that were broadening their community, their real community that they had found. And off-screen, all this work had been done. Sammie had done the work to build a life for themselves. Clearly, something happened. There was a whole other thing we didn’t see, and I feel like so much of storytelling about the trans experience or queer stuff is all very built around coming out, and what I wanted to shoot for here was like, “All right, but what about afterwards, when you keep having to come out, and come out, and come out, and come out to people all the time?”

SN: How did you approach rendering how Sammie makes peace with that old friend and that past and embraces who they’ve become and where they’re going?

ML: Friendship is a very sticky, thorny, weird thing, and it means a lot of different things to different people. I didn’t want to get too Men Are From Mars about it, but different types of people tend to have different kinds of friendships, and straight men have very different friendships than straight women, than queer women, than nonbinary people. It’s all about what you put into it, and friendship is a relationship that has to be maintained, and work has to be put into it. The way that queer people are friends is different. It’s not special or magic or anything, but it is the material condition to necessitate different types of relationships for queer people. It’s not controversial to say it, I think. There’s this friction between that [queer friendship] and an old college male friendship, and I think a lot of the journey of the book is Sammie trying to jam a square peg into a round hole and figuring out that’s not really a thing that you can do.

SN: How did you come up with the idea of the characters hunting their own clones? It seems like a perfect way, at least in the world of this book, for Sammie to confront and reckon with themself.

ML: We’re talking about letting go of your past life. I think every trans person has that fantasy of going back in time and talking to their younger selves. Everyone does, right? I think with queer stuff generally, and transition specifically, a lot of us would have liked to know earlier, right? For a lot of reasons, both socially and medically and whatever else. So, I think if we’re talking about making peace with our past, the idea of having to interact with the actual literal yourself from the past, or a sliding-doors version of you, or the way that the capitalists see you as just a warm body made of your genetics that has no autonomy in any serious sense of the word … there’s a couple of different contradictions I was trying to draw out where Sammie was going and where the rest of the world that they were dropped into was going.

SN: Was there any part of this story or a scene that was particularly fun to draw or write?

ML: I had a lot of fun with the big sequences underwater just because I’ve always liked drawing sea creatures and submarines. I had a lot of fun with drawing a party inside of a submarine, which was like a weird little challenge. That was a lot of fun because when I was coloring it, I was trying to time the lighting in the panels to match up with flashing music. So, I was spending a lot of time just singing techno music to myself. And the other thing, eternally, is that background gags are fun for me to think of. I love thinking of fake advertisements, which there are a lot of in the book.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sarah Neilson is a freelance culture writer and interviewer whose work regularly appears in The Seattle Times, Them, and Shondaland, among other outlets. They are an alum of the Tin House craft intensive, and their memoir writing has been published in Catapult and Ligeia.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY