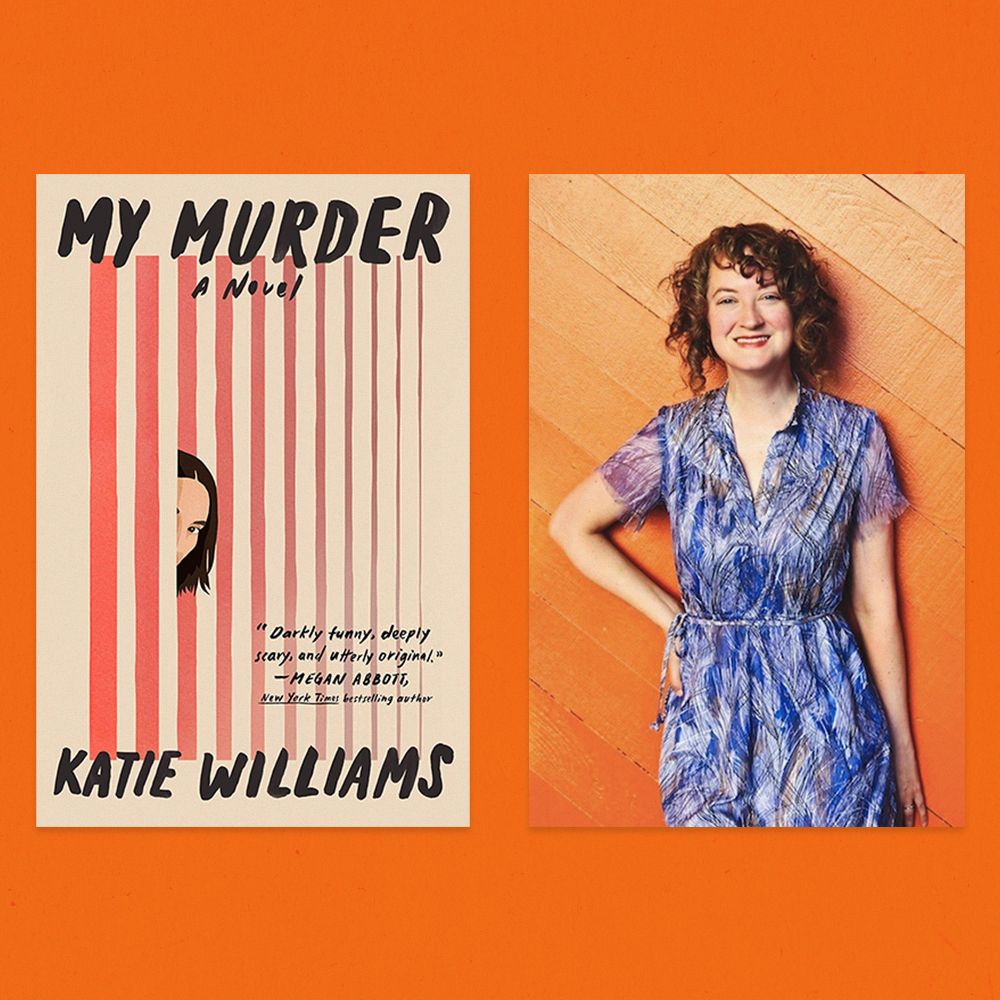

My Murder by Katie Williams is part murder mystery, part speculative fiction, and part meditation on identity. The protagonist, Lou, was murdered before the novel started. Or well, not Lou exactly. The Lou we meet in the beginning of the novel is a clone to a Lou who was murdered by now-imprisoned serial killer Edward Early. She has all the same memories, minus the last day of her previous life, and she loves her daughter and husband dearly. Even if technically the body that held her daughter wasn’t hers.

The first half of the novel is given over to reconciling a person’s ever-changing identity. Lou, who’s dealing with the same memories and expectations of the first Lou, is a fascinating look at how a person interacts with the expectations of those around them. But then, Edward Early insists to Lou that he didn’t kill her, and the fragile balance of her existence is upended right as she’s starting to get fully settled into her life.

Williams, who teaches creative writing at Emerson College, published three novels before My Murder. Her previous novel, Tell the Machine Goodnight, was also a lightly speculative story about a woman who created personalized happiness plans for wealthy clients while struggling to keep her own child content. An earlier YA novel called Absent interrogated a similar question as My Murder: It follows the ghost of a teenage girl who’s trapped haunting her own school until she can figure out who murdered her.

Shondaland chatted with Williams about the ethics of murder-mystery stories, the infinite possibilities of asking relevant questions through near-future speculative fiction, and the pressures women face to perform in so many aspects of their lives.

SHELBI POLK: So, my first question is almost always as broad as possible: Where did this story come from?

KATIE WILLIAMS: So, I love reading murder mysteries. I love reading lots of genres, but murder mysteries are one of my favorite genres. And it came from an uncomfortable feeling I had about being a murder-mystery fan, which is that it’s so often around a woman’s death or violence against women. There’s a dead woman’s body in the center of the story, and she’s just this kind of object in the story. Everyone else is working to figure out how this violence was done to her. So, my question as a writer was like, “Is there a way I can bring this woman back into the story so she can have voice and agency?” And that’s where my main character, Lou, came from.

SP: I feel the exact same way. I used to love murder podcasts. And I think there are ways to do it right. But then so much of it is so exploitative.

KW: When it becomes used for entertainment or romanticized, it can become uncomfortable. At the same time, again I’m a big fan of these stories, and I’m really curious still about why I am so drawn to them and sometimes raising an eyebrow at them.

SP: I think it’s so healthy to be critical of the things we love, to a degree. I loved how much time you spent on Lou as the “perfect victim” and how much that mattered to the events of the story. Could you dig into that a little bit and why that matters so much in telling these stories?

KW: I guess the idea of the perfect victim gets into the romanticization of them. Why is it more tragic or more appealing if a young, pretty mother dies? What does that say about who we’re valuing and the way we’re looking at violence? I think it’s really fraught, but it was something I wanted to explore in the book. What happened as I wrote was I was sort of investigating this question and this feeling I had as a reader and a fan of murder mysteries or true crime. And then, that question started opening up in different ways. And the book ended up, or the reading experience ended up, becoming about agency as a woman in other ways. Agency, the limitations of agency, and expectations around being a woman. And that got into a lot of different areas, like family and career and motherhood.

SP: There’s so much interesting tension within the freedom-versus-responsibility theme or perhaps, freedom versus expectations. Lou is not a blank slate, but in some ways, she is.

KW: I mean, it had plot necessity or plot value for me that she can’t remember what happened, so she has to investigate her own murder. But yeah, you’re right. It has somatic value as well. I don’t know how philosophical you want to get here. But [I wanted to explore] the ways in which we build self, the ways in which we tell stories about who we are, and the ways in which we let societal expectations or societal stories about who we’re supposed to be impact the way we’re building ourselves or constructing our lives and our idea of self. … I don’t know that I have any conclusions. When I write novels, it is sort of an investigation for me. And I think if I’ve done my job, I don’t arrive at answers, necessarily. I just arrive at maybe more questions or possibilities.

SP: The technological atmosphere in which they’re functioning seems like something we’ll be experiencing in 10 years. It’s also similar to your last novel. What about this near-future-esque, speculative vibe intrigues you?

KW: I am interested in looking at just a step or two out from where we are now. As a writer, it allows me to, hopefully, create worlds that still feel very character-centric and lived in. It’s just easier for me if I’m going 10, 20 years in the future versus hundreds. Plenty of writers imagine hundreds of years out and do brilliant character-centered work, but for me it’s easier to look just a few steps out. I think it has a great interest and tension on what’s happening now because it just reflects back that little bit to where we’re at. When I write speculative or futurist, I really do see that kind of work as a trajectory and commentary on where we are now — the reality of the here and now.

In particular for My Murder, the cloning was a way that I could bring the murder victim back. But as I kept imagining this future, other opportunities came up for me as a writer. For example, her job as a touch therapist, which is a real job. But to have it, she does it through these virtual skins so she and her clients are in this virtual space and can look however they want to look, and that had interesting imaginative and somatic value for me around identities, the bodies we live in, which of course ties in to that central question of violence against women and using it as entertainment. And so, these future imaginings are ways for me to look at what’s happening now and also ways for me to look at different things around the characters and themes in my work.

SP: I thought it was so interesting how this and your last novel, Tell the Machine Goodnight, both have a lightly speculative care profession. Lou is a touch therapist who operates in a virtual space, and Pearl is a “happiness technician” for a company with a “patented happiness machine.” None of that feels very impossible, and it was a really interesting way to highlight some current emotional issues with women in the workplace.

KW: So, the care professions were exploring being a woman in this world, the expectation of women to care, and then also the real joy and value that I find [in] myself as a woman in providing care. That’s complicated, right? And then the induced empathy for Edward Early. As a writer, I got to the scene where — and I knew it was coming in the middle of the book — I was gonna write a serial killer. I wrote a short story, when I was 20 years old and getting my bachelor’s in creative writing at University of Michigan, between a victim and a serial killer. And I could not do it. I didn’t have the craft to do it. But I came back to the scene 20 years later. I had a lot of anticipation and fears around writing it. And so, I just thought, how can I subvert expectations? How can I upend the Clarice Starling/Hannibal Lecter scene but still be true to the fact that this is a man who’s done great violence? That became an opportunity because I was able to imagine this technology that he has been chemically given empathy. And then, I imagine what would that be like to be someone who didn’t have that, and all of a sudden, it’s being induced in you? What does that feel like?

SP: I mean, to some degree, it’s what we want, right? Edward Early was a serial killer, and he should feel bad for what he’s done. But even though that’s true, wanting him to feel guilt is almost another way of wanting to see him suffer. I had not considered that option until you wrote it.

KW: I love your observation, though, that it’s like a way for him to suffer in a sense. And then, maybe it’s a little bit of wish fulfillment, sure. For, like, recognition and accountability. But you can’t force someone else to have it. I guess in this book, he is forced through this treatment he’s been given.

SP: You have a YA novel, Absent, that explores a kind of similar question, the fallout of a murder, but through a more mystical means than as speculative. What was it like to deal with this theme again? Was it difficult to differentiate, or was it fun to revisit?

KW: Well, I have two young adult novels that I think are like earlier ways of trying to write into this same topic. Space Between the Trees, my first novel, is a girl detective story, but a troubled girl detective story. And then Absent, my second novel, is also young adult. It’s a ghost story told from the point of view of the ghost, and it’s about a teenager who is investigating her death. So, a similar sort of mechanism was used. Obviously, this is really rich territory for me. I feel like I’ve been able to explore it multiple times using different tools and perspectives.

As far as moving from young adult to adult, I’ve been asked this question before, and I just really don’t really differentiate a ton. When I’m writing young adult, the characters are younger, and so I just try to be with where the characters are, where they’re at. And then I guess when I’m writing adult, it’s the same thing except the characters are older. So, it’s a different point in life, a different vantage point.

SP: So, we don’t want to not write about violence against women. We don’t want to ignore it. But where do you think the line is between responsible and exploitative and gratuitous? How do you write about these topics well?

KW: The ethics are complicated or can be complicated as an artist. And I do believe it’s important to think about the ethics of one’s work. There’s certainly things I think about how much violence and putting [it] on the page and in what way. If the book is aware of the violence and can unpack the violence and draw attention to it, I think that’s another way to explore without ratifying the violence. I don’t know if I could come up with a set of rules. But I think that that kind of awareness is important. And in signaling or presenting that awareness to your audience. And making sure the victims are recognized as people, as humans, instead of being used as devices or objects, would be another important piece of that.

Shelbi Polk is a Durham, North Carolina, based writer who just might read too much. Find her online at @shelbipolk on Twitter.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY