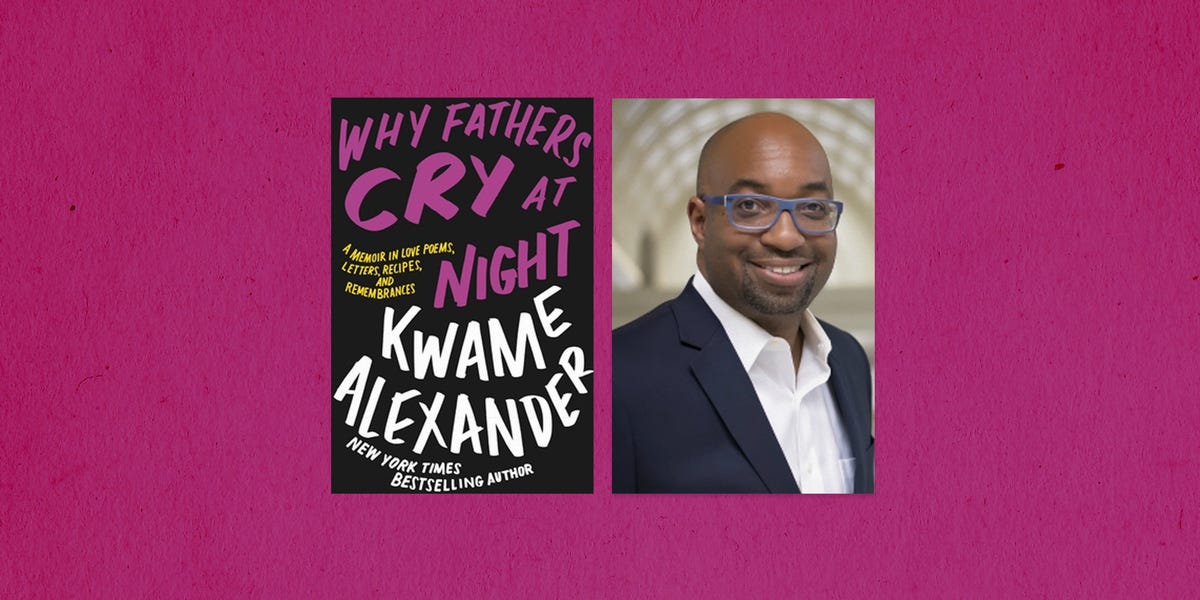

As the author of 39 books, including The Crossover, The Undefeated, and Rebound, it's safe to say that Kwame Alexander has had a writing career one can only dream of. And now, the New York Times best-selling writer explores the depths of an emotion that’s bewildered writers for centuries: love.

His latest book, Why Fathers Cry at Night, is a hybrid memoir mixed with recipes, love letters, poems, and prose. Alexander gives readers an intimate look at what love is — what it can be, what it should be, how he has come to understand it. In each moment, Alexander examines his relationship to love and how it has impacted — or will eventually impact — his daughters, the center of this memoir. From the love he has for his mother to the complicated love he has with his father, to the love of the women who brought his children into the world, Alexander lets readers witness it all. The memoir is at once tender and honest, and Alexander doesn’t pretend to have all the answers.

Alexander is a poet, educator, and regular contributor to NPR’s Morning Edition, as well as the executive producer, showrunner, and writer of The Crossover TV series. Shondaland spoke with him about finding grace, falling deep in love, his relationship with Nikki Giovanni, and how grief and loss can push you further into community.

ARRIEL VINSON: In the introduction, you said that you set out to write a collection of love poems, but you instead decided to write about learning to love. Tell me more about that shift.

KWAME ALEXANDER: The goal was to just write a book of really fun, interesting, engaging love poems. As I got into it, I started seeing that the poems were linked. It was almost as if I was telling a story, and I thought, “Maybe there’s a story here that needs to be explored.” Then I began consciously writing pieces to fill in some of the blanks in the narrative. And I wrote prose pieces to give the poems more context. Then I remembered recipes.

Before you knew it, I realized that I was writing not just about love, but about my relationship to love, my understanding of it, my remembrances of the early inspiration and influences of how I would eventually learn to love. And my editor said, “It looks like you’re writing a memoir.” And I said, “Oh, well, I guess I am.” But that didn’t come until maybe 75 percent of the book was done. It was a cool thing to realize and then go back and try to shape.

AV: Hence the title; you spend a lot of time examining your relationship with your father, as well as looking at your own experience as a father. What did exploring this illuminate for you?

KA: It illuminated that I need to have a little bit more grace when it comes to my dad. All these years, I’ve been looking at the stuff I don’t think he did right. And maybe I was a bit disappointed or frustrated or even angry at some of the interactions that he and I have had. Now, being a dad of a teenager and an adult woman, I want them to offer me the same grace, and I can see what I’m getting wrong. It’s harder than I thought. I can’t be so judgmental when it comes to my dad.

So, I wrote this piece after I had written some really hard critiquing pieces on my father as a father and a husband. I went back and was a little more gracious, and wrote this letter called “A Letter to My Father,” where I tried to look at the holistic approach to examining his fatherhood and how it helped shape me into who I became. But that was only after having written some very self-critical pieces and judging myself and realizing I shouldn’t be so hard on either one of us.

AV: The recipes in Why Fathers Cry at Night serve as a commentary on lineage and how love is expressed. Why did you lean on recipes for the memoir, and how did the idea come about to add them?

KA: I moved to London in 2019, and it was a big life change for me. One of the things I decided to do in this new phase of my life was teach myself how to really cook. And not just cook anything but teach myself how to cook some of the dishes that my mom made as a way of getting closer to her, as a way of remembering her, as a way of dealing with my grief over her passing.

Cooking became a big part of my healing and my joy, and I loved it. I loved shopping for the food, the ingredients, and I loved preparing the meal. The biggest thing I loved was sitting across from my kid while she tasted this thing and inevitably critiqued it. There were those few times where she was like, “This is amazing, Dad.” And that felt so good.

As I was writing the book in London and writing about my mom, it just made sense that I would include that experience of having taught myself to cook as a way to remember her. Then I began thinking about some of the other meals that I’ve learned how to cook or have eaten over the years and how they played a role in who I am. It seemed like it would fit within the hybrid nature of this memoir as a way to keep memory and seal my identity.

AV: The recipes are definitely an archive of some sort.

KA: Yeah, because they [my family] ain’t write down their recipes! How are you going to not write down the recipe of the best dinner rolls ever created? A lot of this was me deconstructing, trying to remember what it tasted like. Trying to remember how it looked. Talking to my aunts, getting what they know. It was a re-engineering. Hopefully, going forward, my kids, and hopefully their kids, will have access to some of these recipes that will do for them what they’ve done for me — which is grounding me in this beautiful memory of family.

AV: In Why Fathers Cry at Night, you talk about how you fell in love, had children, and the love you shared after divorce. Tell me more about the space you made for the women you loved.

KA: I fell hard in love with both of them, and I wanted to capture what that feeling — that passion — was in the beginning. I don’t spend a whole lot of time on how it ended, but I wanted to talk about how to part as lovers. How can that be done in a way that’s still familial and pays tribute to where you were when you started?

The goal was that my two daughters would be able to see how their dad loved their mother. To give them some context, for 10, 20, 30 years when they’re wondering what happened and they really want to delve into that. ’Cause the teenager doesn’t want to talk about it. But maybe they’ll have some context that will paint their mother and me in a way that they can understand and maybe appreciate in a more graceful way.

AV: Why Fathers Cry at Night also explores your relationship with literature, from your parents being storytellers to getting to college and running away from words, to your relationships with other writers we consider literary greats. What made you include your relationship with literature?

KA: I remember realizing how much in love it appeared my dad — who never said, “I love you” — was with books. His whole life was centered around books. There were books everywhere, and it was annoying, intimidating, and boring. Like, are they really that important? Because really, all of your life, you don’t have anything else? And of course, I’ve written 39 books.

When I’m on the road and my kid’s like, “Oh, you going to travel again?,” I realized that in some ways, I’ve become my father. It’s been a constant struggle to figure out how to balance this life that I love with the other aspects of my love that matter — the familial love, the romantic love — so I can be a little bit more balanced than my dad.

But how I got here when I tried in every way not to get here, I find really interesting. This is not where I anticipated being. But you’re talking about a 27-year career, and I absolutely love it. The idea was to write this book as a way to show my two daughters in particular how I love, and books are a huge part of that.

AV: I loved reading about when you were taking Nikki Giovanni’s classes in college and getting C’s. It told us so much about how you became the writer you are. Why were those classes in particular part of the memoir, and what did you want to say with that?

KA: The first thing I wanted to say was, whereas my immersion in literature started at home with my parents, at a certain point writing became a serious interest and endeavor, and that happened in college. I wanted to paint a picture of where that turn happened in my life where I decided, “Okay, writing may be the thing.”

And number two, the idea was I’m writing to my daughters, and I’m trying to teach them things that I’ve learned or show them things that hopefully they’ll learn from something I went through. And my experience with Nikki over 30 years really evolved from what I determined was a dislike for each other (in my mind) to a mother-son love.

It was important to document that love story — there are several kinds of love stories in this book. And I wanted to pay tribute to her as a woman. One of the things she said to me when my mother passed is “You still need to know you have a mother here.” So, it was important to document, and pay tribute to, and share that unlikely love story because it has defined so much of who I am as the writer I am today. And at the same time, it’s given me a place to go for Mother’s Day. It’s a beautiful thing.

AV: Throughout the memoir, you move through joy and loss in a way that isn’t linear, but especially at the end, you grapple with grief and how you eventually came out of that. It felt like those emotions were moving with you.

KA: I felt the same thing in writing it and just in living it. There was a point back in 2017 where my career was just really on supercharge. I was winning awards, selling millions of books. I was “the guy.” And I couldn’t sleep. And I was unhappy. Because I was on autopilot with my career and working and writing and loving books and being immersed in literature. My mother had passed, and my marriage had fallen apart, and my daughter had stopped speaking to me. And my tween was becoming a teenager, and she didn’t want me to hold her hand walking to school anymore.

But I wasn’t dealing with any of it. It was dealing with me. And writing the book forced me to say, “Okay, dude, you need to deal with this stuff.”

AV: There’s a poem, “A Poet Walks Into a Bookstore,” and the narrator mentions that there are only books about social justice but no books about love, and you can’t change the world without love and people. I would love for you to speak more about community in the memoir.

KA: When I look back on my childhood, the village was so important to who we were and who we could become. The Sunday dinner gatherings of all your cousins and aunts and uncles at your grandmother’s house. The Saturday night party at your grandmother’s house with people playing dominoes and spades. No matter what was happening during the week, the stressors of life, the homework or the test, or the argument between your mom and your dad, or whatever’s going on, you know that on Sunday night, it’s all joy. That Sunday dinner, it’s all love. To be able to have that as your bookends, as your anchors, that’s how our ancestors, I think, survived.

There’s no way you can stay in the space of challenge and trauma and tragedy without having the hope, the faith, and the joy. And the village, the community that I’ve had throughout my life have been extensions of that idea. That’s life-giving, and it’s lifesaving in so many beautiful, powerful ways.

And the other answer is there are friends in my life who are partly responsible for me being able to keep growing as a man because they check me. In order for your friends to check you, they got to know that you’re open to being checked and you’re trusting. And I haven’t been that person for so long. I was in Puerto Rico with two friends of mine, two guys, and I was like, “Yo, have I been vulnerable and sharing and open with y’all over these past 20 years?” And they both laughed and said, “You’ve always been surface level.”

It was a moment where I was like, “Dang, that’s not who I want to be.” It’s not serving me. So, I’ve tried to be more of an open book. I’ve tried to be more trusting with my feelings and thoughts, and therefore that has opened the door for my friends to be more open with me. The community is only as strong as you allow yourself to be a part of it.

AV: And then there was a conversation you had with yourself at the end of the memoir about loneliness, love, and loss, and how they’ve shaped you. And how you maybe haven’t been loving yourself or focusing on loving yourself as much as you could’ve been. Where are you now?

KA: The book was the first step. The writing about it is just the acknowledgment. If you want to actually change, if you want to actually become better, you have to actually do the work. That’s beyond the writing.

So when you ask, where am I now? I am trying to do this work, and I find it so hard and so rewarding. For example, I’ve never been a person who has hard conversations. I have had some of the hardest conversations in my life with my dad and with others. And they’re never as hard or as bad as you think it’s going to be. And I’ve felt so much better after having them.

AV: Is there anything else about Why Fathers Cry at Night that you want to talk about?

KA: I’m doing a Why Fathers Cry podcast, talking with other fathers and husbands and sons, and these conversations have been amazing.

They have been so enlightening. And the cool thing is I realize I’m not the only one that’s going through this. I’m not the only one who just had a 20-minute argument with their 14-year-old because she wants to watch Bridgerton. It’ll be out in June, I think.

AV: I can’t wait to listen. And what else are you working on now?

KA: I’m producing a reality show called America’s Next Great Author. And a couple other books.

Arriel Vinson is a Tin House workshop alumna and Hoosier. She earned her MFA in Fiction from Sarah Lawrence College and received a B.A. in Journalism from Indiana University. Her poetry, fiction, and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Catapult, Booth, Cosmonauts Avenue, Waxwing, Electric Literature, and others. She is a 2019 Kimbilio Fellow. She tweets at @arriwrites.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY