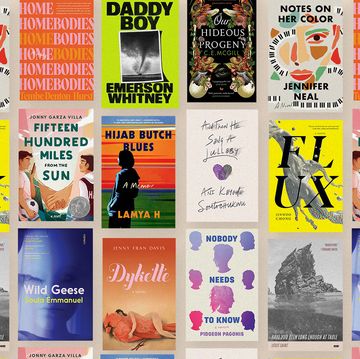

Gabrielle, the main character of Jennifer Neal’s new novel, Notes on Her Color, is a Black and Indigenous girl living in Florida in the ’90s who has inherited an ability passed down the maternal line for generations — the ability to change the color of her skin. She can pass as white, but her skin also turns every other kind of color (even metallic). It is one of the things that bonds her to her mother, Tallulah, who teaches her about this power and how best to harness it. The two live in a cold and sterile house with Gabrielle’s father, a Republican lawyer who attempts to control them both. When Gabrielle graduates from high school, she is coerced into staying home under her father’s thumb under the auspices of beefing up her extracurriculars for her pre-med college application. The new piano teacher her father hires, Dominique, a queer Jamaican woman, helps reveal the vital world of self-acceptance that is possible for Gabrielle. Notes on Her Color is a sweeping story of family, community, coming of age, trauma, mental illness, and the life-giving power of art.

Neal, a MacDowell fellow, currently lives in Berlin and has had her writing featured in publications and outlets like The Establishment, Playboy, NPR, and more. Shondaland spoke with her about parent-child relationships, intergenerational inheritance and core identity, and the specific lushness of Florida.

SARAH NEILSON: What was the initial inspiration for this story and these characters?

JENNIFER NEAL: I’ll start with the most apparent and obvious narrative device, which is the color-changing mechanism that I use to guide the story from beginning to end. That was partially inspired by the whole Rachel Dolezal fiasco. I think while that captured most of our imaginations, what it did for me was it really tapped into a lot of the stories that I had observed and listened to, and seen in real life, about how passing actually plays out in a 3D landscape outside of books; without the magic, without the folklore, just how it operates in society as part of critical race theory. I thought it to be very interesting that somebody was actually taking this on as an ability to pass into certain spheres, and I wondered what it would look like if I could reverse that somehow and make it not just like a power or ability (not to be too reductive), but to make it a connecting attribute between a mother and a daughter. Because how we learn about different social constructs like race and gender and sex and all that comes from the way our parents perceive the world. I wanted to show how a mother teaches her daughter about race, but I didn’t want to discuss that through the usual, you know, beware of the cops, observe your surroundings, respectability, politics. ... All of that is in the book, but I wanted to show it through a different conversation where it is still a matter of survival, but at the same time it’s something that bonds these two people together. So, the story kind of started its nexus with that situation, but it gave me an opportunity to revisit mothers and daughters, which is something I’ve always wanted to write.

SN: What draws you to writing that mother-daughter relationship and that specific kind of intimacy?

JN: It’s always been my belief that that relationship between a mother or a birthing person and their child is the most intimate relationship. It’s the first sense of physical connection; it’s the first sense of love or mental acuity that you receive in the womb. This person is your universe, and through them, you are introduced to food, to light, to oxygen, to music, to colors, to patterns, to touch, and that is an intimacy that I think supersedes all other forms. I never grow tired of reading stories like that. My favorite books tap into the complexity and the weirdness and the changing of the guard between one or the other. And the jealousy that often takes place between one and the other. ... I was reading one of Elena Ferrante’s books when I was writing the earliest draft of this book, and I just remember being utterly compelled by how she explores childhood friendship, and how that blossoms into motherhood, and how that changes the dynamics between friends and between family. It just seemed so powerful to me. I also think part of it comes from the fact that there are so many social expectations that are placed onto moms and placed onto birthing people that are really just antithetical to what it means to be a parent. It’s so judgmental, it’s incredibly restrictive, and it’s incredibly misogynist when it’s actually supposed to be this powerful connection between two people that everybody else is trying to regulate. And I feel like I am seizing back a little bit of agency in that whenever I read a book that rejects those principles and whenever I write a book that rejects those principles.

SN: Can you talk about how you were thinking about inherited stories and the gaps in those stories while you were writing, and how that shapes the narratives we tell ourselves about our own lives, and specifically for these characters?

JN: There was an essay I read by Toni Morrison a few years ago, and I’m paraphrasing here, where she spoke about how she had never read a book that was written through the archive’s perspective of enslaved people, and that is part of what inspired her to write Beloved. I was just really moved by that, this idea of giving a voice to the voiceless. Because what is so common, especially in African American families, culture, and genealogy, is that we really have a very narrow idea of our origins because slave records have erased so much of that — eroded names, eroded places of origin and places of birth. And what I have seen happen, and what my family has also participated in, is this filling in the gaps. We don’t have any idea what happened before then, but what could it have looked like? That is part of the foundation of oral storytelling and oral history because a lot of those records don’t exist.

I think there is a kind of power — that might not be the right word, but it’s the only word that’s coming to mind — in not letting the white gaze be the sole determinant of who you are and what that identity is. A lot of people do this when they’re growing up. They ask their parents, “What was your grandma like? What was your grandpa like?” I did that, and my mom did that, and my cousins do that. And I think that’s really beautiful because it may or may not be historically accurate, but there is a kind of truth in this where you’re getting the perspective of an elder, and that is in turn shaping a part of your core identity. That can be destructive, or it can be healing. It can be a lot of different things, but it’s something that most people undergo. With this story, I wanted to give [Gabrielle] a sense of a background. I wanted her to have something that a lot of people in real life don’t have, which is a sense of her own history and a sense of her origins. That, to me, was doing a service, whereas in real life that often does not exist. So yes, it’s obviously a wild piece of fiction, but in a way I’m kind of taking a reparative approach where I’m saying we all have this history — it’s just a matter of do we know, or do we not know? I wanted her to know, and I wanted her to have that be part of her core identity so that that’s not something I would have to question throughout the story. She has this ability that ties her to her past, it ties her to her ancestors, it ties her to her mother, and that gives her a very strong sense of self, even if part of that is destructive. So from there, I was able to explore other things without her constantly questioning grandparents and great-grandparents and all that other stuff that we do in real life as descendants of enslaved people.

SN: I noticed this contrast between the sterility of the white house that Gabrielle’s family lives in, and how it’s just so cold there, and all the color and vibrancy and the art that seems to have to do with queerness. How were you thinking about queerness as part of the story?

JN: I was very conscious of trying not to make queerness an antidote to violence and misogyny. At the same time, I was also trying to be very mindful of how the road to self-acceptance when it comes to one’s own sexuality is incredibly messy. Like, if you had told me when I was 10 that I would grow up to be a queer person living in the queer capital of Europe, I’d be like, “That doesn’t make any sense.” I think what I was trying to highlight more than anything else was that the road to self-acceptance goes in a million different directions. I really wrestled with the idea of how much trauma I show for a person on that path, because life is traumatic enough on its own, but I didn’t want to shy away from it either. Because especially in this particular timeline, the idea of being queer in this conservative and really restricted household would have come with immense challenges. I had to be honest with myself about that in order to make it convincing to me when I was writing it. Having said that, what I decided to do is that she did not have to be sexually assaulted to undergo that process. I also wanted to drip in little moments of her own discovering and noticing things and other women around her before that incident [of assault] happened, because that’s also part of her personality, and I wanted to assert that. At the same time, when we talk about color and queerness, I think the color and the queerness definitely weren’t antidotes to the violence and misogyny. I think they were antidotes to her living in a household where she’s told who she has to be. Being vibrant and embracing colors and embracing music and embracing art, I think are very queer practices. Not just historically; I’m talking about bell hooks’ philosophy where you don’t subscribe to the standard deviation of what you’re supposed to be. … You feel put out and cast out from this world, and you have decided to create a new one with a new community where you can be yourself and you can be vibrant. I think of it more as a celebration rather than a medicinal treatment to the violence that she experiences.

SN: Would you elaborate on the idea of freedom in the book and how that ties in with a coming-of-age narrative?

JN: I think a lot of classic love stories are about ownership — one person staking claim to the other, holding on to each other and possessing one another, and I think love is often encapsulated as that in literature. That’s how it’s branded. “I want you. I desire you. Do I get you or not?” Which is very restrictive. Perhaps I feel inspired by my queer community and queer literature and how even the concept of family is often picked apart, unpacked, reinvented, and has been redefined to say like a chosen family. How community cannot necessarily be a substitute, but an extension of family as well. So, I think a lot of this stems from this idea that you are free to be who you want to be, and nobody has the right to tell you. We don’t have to conform to any particular way of being. I think that is a beautiful thing, and I think at its very essence, that is an act of love. When you provide space for somebody to be who they want to be, that’s not about ownership. At its essence, love is about freedom. So, here [in the story] you have this incredibly charismatic, super-cool, larger-than-life piano instructor who is all about the color and all about the vibrancy and all about the spice, and that is polar opposite to what Gabrielle knows. All of that is beautiful, but it’s a little bit ... not superficial, but it’s surface level. What Dominique really gives to Gabrielle is the freedom to be who she is. But that should not come at the expense of who Dominique is. And even though we don’t necessarily know if they end up together and stay together or not, what we do know is that in Dominique’s actions, she chooses to love this person in a way that sets her free on the course to become who she wants. And that, I think, is what makes it a very hopeful story in the end.

SN: It seems like Florida literature is having a moment the past few years. What is it about Florida that’s so lush and fertile for storytelling?

JN: It’s really simple. It should not exist. This place is the literal 3D manifestation of every kind of weird, wacky magical realism, fantasy, bleak political satire, and environmental, ecological world-building combined in one place. If the United States were like a pond, Maine would be like those beautiful lily pads floating on top, and Florida would be all the stuff at the very bottom. It would be like the plastic beer six-pack rings, it would be like the used condoms, but it would also be like the chupacabra. It would be the mythical creatures that everybody says they’ve seen, but nobody knows if they’ve seen them. It’s everything. It’s just full of life. It’s full of weird reptilian dinosaurs, animals, and politicians. It is this weird, bizarre, magical, beautiful, crazy, totally messed-up, and dysfunctional place that is perfect for fiction. I don’t know why there’s not more. And writing a kind of anti-fairy tale there just feels really right because it’s kind of an anti-fairy tale moment.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sarah Neilson is a freelance culture writer and interviewer whose work regularly appears in The Seattle Times, Them, and Shondaland, among other outlets. They are an alum of the Tin House craft intensive, and their memoir writing has been published in Catapult and Ligeia.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY