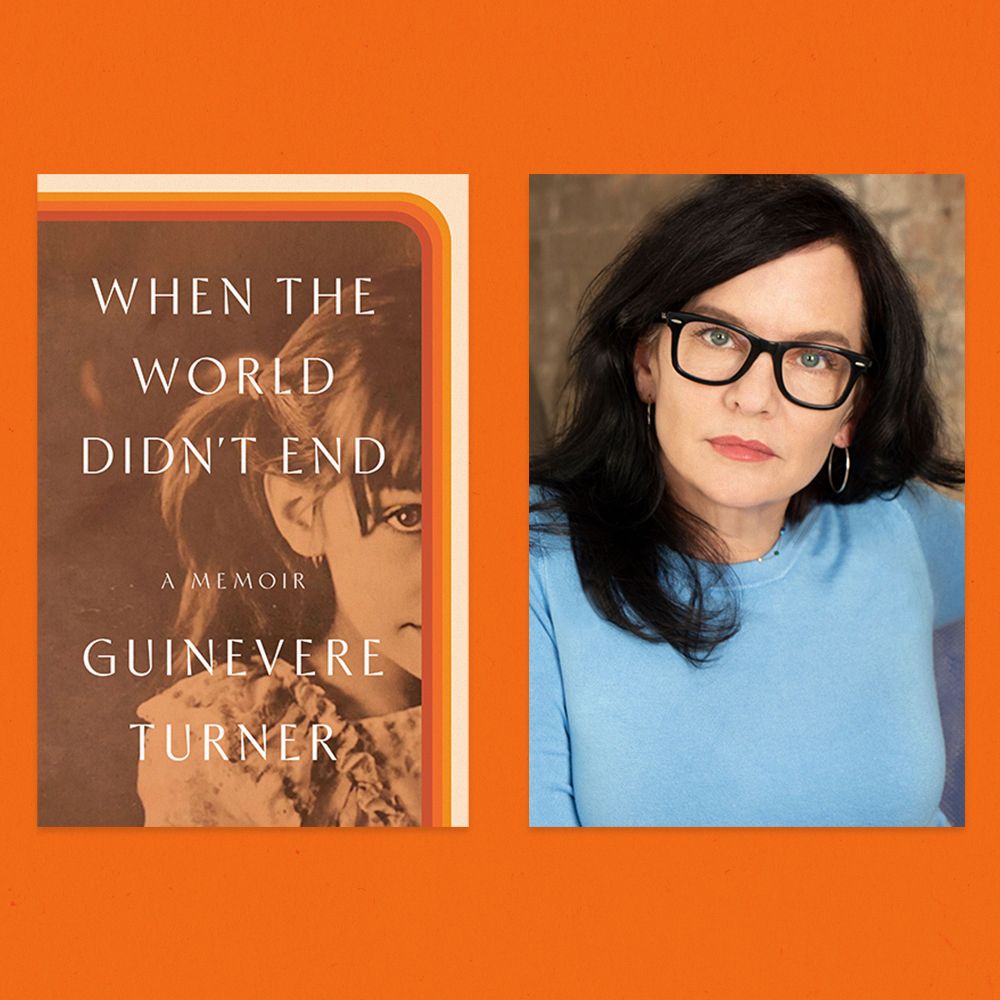

Guinevere Turner has been a writer for nearly her entire life. Long before she penned the screenplays for films like American Psycho and The Notorious Bettie Page (and acted in or directed multiple other films), she was scribbling in her diary every single day, chronicling her young life as part of the Lyman Family — a large group that has since been described as everything from a family to a commune to a cult. It is those diary entries (and a 2019 essay in The New Yorker) that laid the groundwork for Turner’s new memoir, When the World Didn’t End.

Told from the author’s childhood perspective without burdening the text with the hindsight and judgment of the adult Turner’s learned experience, When the World Didn’t End is a faithful telling of a harrowing upbringing and an uncertain adolescence all the way up until the moment she must decide whether to return to the only family she’d known for so long (before being forced to leave with her mother and sister) or head off to college. It is a poignant and wholly engaging memoir that paints a vivid picture of just how far Turner has come in her life and career.

Shondaland recently caught up with Turner to discuss her memoir, how she’d been unknowingly laying the groundwork for writing it for years, her screenwriting career, self-care, and so much more.

SCOTT NEUMYER: This had to have been a difficult book to write. How are you holding up?

GUINEVERE TURNER: It’s daunting. I’ve just started doing interviews about this book. I’ve done a million in my career, many promoting various films that I’ve been involved with, but there are two things that are very different about this. One, it’s very personal; obviously, it’s literally about me. And two, unlike movies where I’m talking about my screenplay or my performance but there’s a billion other people, it’s also all me. I have an editor and all of that, but the daunting part is that I’m responsible for it on this sort of massive scale that is both internal and external. I have written about real people, and most of them are alive; probably all of them will read it. So, I’m constantly calming myself. The way that I calm myself is by asking, “What’s the worst thing that could happen?”

SN: You’ve been involved in so many movies where you’re a smaller part of the big puzzle. Does having this book be all you make it feel more rewarding?

GT: It’s a double-edged sword. I’m very collaborative. Even as a screenwriter, most of the many of the movies that I’ve written, I’ve collaborated with the director. Not all of them, but many of them. And I like that. And as an actor, I’m super-collaborative. You kind of have to be. There’s a relief in that kind of collective creativity. It took me a long time, especially when I was working in TV as a writer, to also realize I can’t control it, and I like controlling it. So, there’s a great thing about having [this book] be all me, which is that I just got to be as weird as I want and tell it however I want. Of course, I have my editor saying things like “What the hell are you talking about here?”

Both my editor and my agent said that the way that I first ended the book was too bleak. They were like, “Can you give us a happy ending?” I’m like, “It wasn’t a happy ending. I just wasn’t sure what was gonna happen to me or if I made the right choice.” It was a huge, huge, huge, huge choice — one of the five biggest choices I’ve ever made in my life — and I know now that I made the right choice, but then I just didn’t know.

SN: You’ve had so much success in film and writing and acting. You didn’t have to come back and tell this story if you didn’t want to. And it’s one you’ve been living and holding on to for many years. Why was now the time to write this and put this book together?

GT: My film Charlie Says that came out in 2019 was about the women who killed for [Charles] Manson and largely focuses on their time in prison. And I’ve been spending the last few decades pivoting away from talking about my childhood when I talk to press because it hasn’t been relevant. I learned the hard way that when you start talking about growing up, that’s all anyone wants to talk about, which is fine, but you have to be up for it. And obviously, if you’re promoting something else, it’s all a digression. My upbringing is irrelevant to this movie, but I can’t not talk about it — then it’ll just seem like I have some goofy secret. So, I wrote a piece that was published in The New Yorker and got over the hurdle — that kind of terror of writing about it. I just didn’t think I could because I just didn’t want them to be mad at me, and I didn’t want to put myself through it. It was a lot to just go back there and reconstruct it all for myself and go through all those diaries, so the answer to “why now,” it’s almost like I tricked myself. I feel like I wrote Charlie Says because I knew that it was going to make me confront the story, and that I was not going to be able to shy away from it, but I didn’t consciously tell myself that.

I tried to write the story in my 20s because I got offered like a big, fat book deal at the time, and because Vanity Fair did a piece on me for my first movie. They did research and wrote a paragraph about the Lyman Family. And then all of a sudden, I was getting all these offers for book deals. I was in my 20s and just made an independent film. We had zero money, and they offered me a big advance, but I just couldn’t do it. I tried again in my 30s, but I just had all this anxiety. I think I also grew up and gained more perspective. But mostly, it was getting over that hurdle, and kind of having to give myself a speech, like “What are you afraid of? And what is this knot in my stomach that lasted for like three weeks while I was trying to write this piece? And again, what am I afraid of? They’re not going to come for me. They’re not violent people.” I just needed these people to still like me. And I’m like, “Why do I need them to like me?” I guess because they’re like my family. You can be mad at your parents, but you don’t want them to decide that you’re a bad person. You know, even though these people are not in my life, it was very, very, very complicated. But I got over it. And once I got over it, and I saw the piece that I wrote go out into the world, and nothing burned down. There was so much positivity from it, especially from other people who grew up in cults. So, I was like, “Oh, I can do this.”

SN: It’s interesting that you say fear was one of the things holding you back because people would look at your screenwriting history and the movies you’ve worked on and think, “This woman is afraid of nothing.”

Perhaps what’s most interesting to me, and one of the things I really loved about the book, is that it’s a self-contained story. You didn’t want to bring your hindsight into it. You talked about how you now have perspective, and that gave you the ability to write it, but you didn’t want to bring that perspective into the story. Can you tell me a little bit about that approach and why you chose to almost remove yourself from looking back on it?

GT: One of the first things I did once I actually signed a book deal and wrote the proposal was that I deliberately chose two of the hardest things that I knew would be in the book to see if I could write them and also to have while I was meeting with editors. I needed someone kind of tough. I didn’t want someone who was going to get overemotional over this stuff because I’m past that point. That’s why I’m here.

The other thing I did was I endlessly read memoirs, especially cult-related and trauma-related. When I read them, I thought the hindsight part wasn’t that interesting to me. And I thought, “I want to write something that lets my reader come on the journey with me and decide for themselves, but also to preserve how normal everything was to me.” I think that makes it more interesting, and it invites the reader to have empathy rather than to rubberneck on a weird story. And then also because I had those diaries, I just thought, “What’s a more pure thing to put into and integrate and to write around than the actual person who was talking?” I actually wanted to get back into her mindset, which is hard. It’s hard to stay there. I really don’t like sentences that begin “if I only did that” and “what I know now.”

Part of my project in writing the book was not to demystify cults, because, you know, it mystifies me, but to show that nothing — even the abusive household I lived in afterwards — is horrible every second. I think there’s something really powerful and true about that.

SN: I love the fact that you were able to bring in those diary entries. It gives your story something really tangible that you don’t often have in memoirs. Were you always a journaler? Did you always have a stack of diaries or journals with you?

GT: It started when they gave us those diaries when I was 9 or 10, and I just took to it really well. It was a kind of faux journalism, town crier. It was a very complex thing I was doing, which is writing personal things, but kind of writing them knowing that they would be read and using it as a way to express regret for something I’d done or be passionate about the right thing I was supposed to be passionate about. All of us got diaries, and only a few of us kept writing. I fill a notebook about every two months with daily writing. And that’s another thing that really affected my way of writing this book because I’ve been doing that since I was a teenager. I would go back and look at something that I wrote in my 20s where I’m talking about a relationship or the meaning of life, and I’m like, “That’s so boring.” What I want to know is “What did that person say?” So, a lot of what I write now, and have been for the last 15 years, is dialogue. I just write what people say because that’s so much more interesting than any of my deep thoughts.

SN: After putting yourself through this kind of emotional upheaval in having to write this book, what do you do to take care of yourself?

GT: It’s funny because I sort of anticipated that people would ask if writing this book provided some sort of catharsis or, you know, release. Halfway through the book, I was like, “Oh, no, I’m just re-traumatizing myself. Nothing about this is therapeutic. It’s hard and it’s emotional.”

I have my sister, who the book is dedicated to, and who will talk to me anytime. She really knows what this means for me to write it and what we’ve been through and how our family still is, so a huge part of my self-care is talking to my sister.

What’s funny too is that I tried therapy. I have a really hard time with therapy. I don’t like it. I’m not comfortable. I don’t feel like opening up. But I have thought to myself, “Now that I wrote this book, I can say to a therapist, ‘Can you read this first?’” Because then we’re already somewhere. That’s so much to explain to someone, and it’s so much to say out loud, and it’s so complicated in terms of what an emotional wreck that has made me.

SN: Yeah, the book already lays the groundwork for your therapy.

GT: Exactly. I also have an amazing dog, so petting my dog and hanging out with my dog and my girlfriend is great self-care when I feel anxious. I’m also up at like 6 in the morning, and before I look at any screens or anything, I write in whatever notebook I have going at the time. There’s something very, very soothing to me about that.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Scott Neumyer is a writer from central New Jersey whose work has been published by The New York Times, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, The Wall Street Journal, ESPN, GQ, Esquire, The Boston Globe, AARP, Parade magazine, and many more publications. You can follow him on Instagram and Twitter @scottneumyer.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY