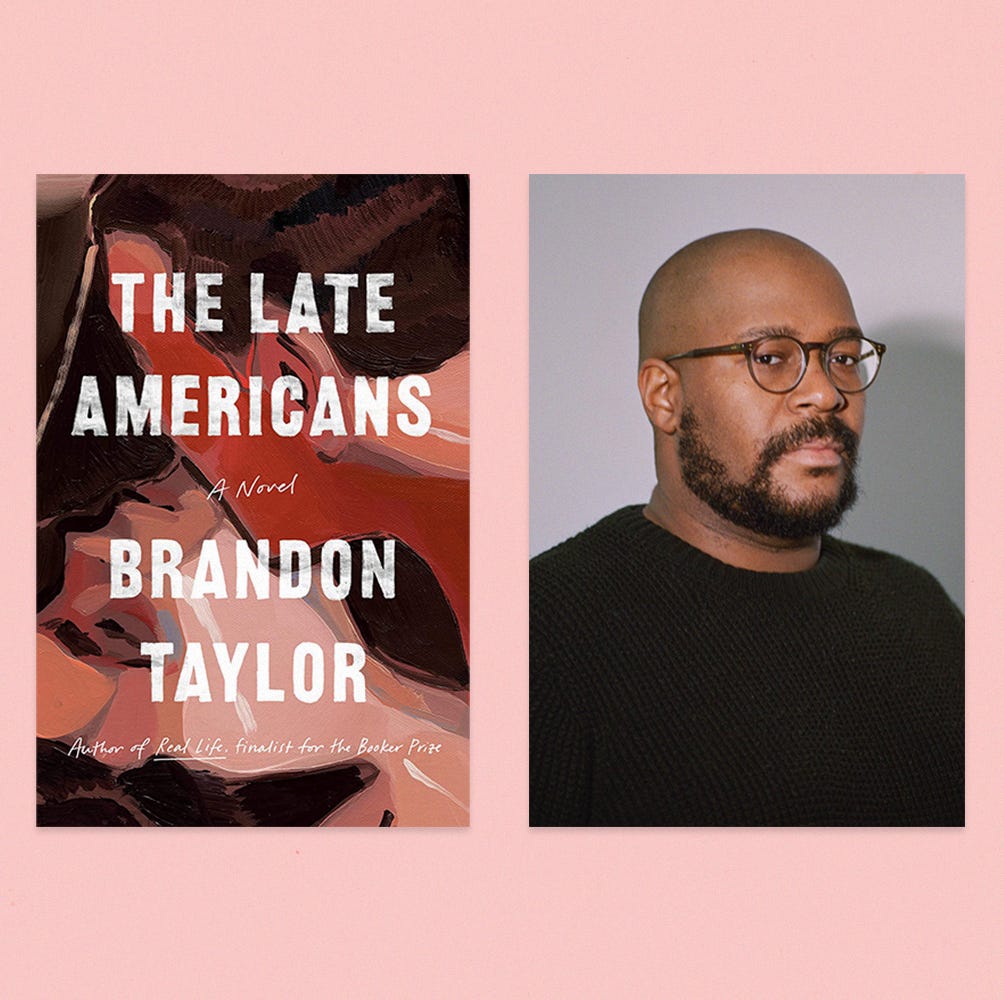

Not only did Brandon Taylor’s new novel, The Late Americans, initially not make it out of the editing process, it also nearly ended his career as a writer. Taylor wrote the novel in about six months, sold it, and spent a year trying to get it into a shape he liked. When he couldn’t, Taylor quit writing “coldish turkey” and took up film photography. “I’d always wanted to be a visual artist,” he says over a recent phone call. “But I never pursued it because my brother was an art prodigy, and I had a whole complex about it.” So, on May 31, the night before his birthday, Taylor decided he would drop the book and check the thrift store for a camera the next day. The secondhand film camera they had in stock was all he needed to throw his creative energy in a completely different direction. “It really did feel like I was never going to write again because I wasn’t going to be able to finish this book,” he says. “And I felt like if I couldn’t finish the book, I was never going to finish another book.” Taylor immersed himself in this new creative practice, shooting six or seven rolls of film a day, and a move to New York only made it easier to get his film developed. “I was like, if I never write again, it’s okay. Because I can still express myself.”

One problem with the book was that it didn’t feel like the kind of novel Taylor likes to read. The Late Americans falls right in between a novel and a short story collection, enough so that Taylor wasn’t sure what it was until his editor declared it a novel. “I have very, very rigid feelings about what a novel is,” he says. “To me, a capital-N novel is like Henry James or Edith Wharton, a very rigid 19th century Anglophone.” Taylor’s loyalty to 19th century novels generated the title The Late Americans (a nod to Henry James’ The American) and nearly derailed his revisions. “I spent a year trying to rework the book to feel more like a Jamesian novel, and it ruined my life,” Taylor jokes. When I ask if it’s “late” Americans as in dead, tardy, or the current stage of capitalism, he says it’s “all of the above.”

As a biochemistry grad student turned successful novelist, Taylor already had some experience reinventing himself. His 2020 novel, Real Life, follows a Black, queer graduate student in the Midwest as his work is sabotaged, and a linked short story collection called Filthy Animals, which mostly follows another set of creatives in the Midwest, was published a year later. The Late Americans is a campus novel, with a majority of the characters attending the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the premier MFA program at the University of Iowa. Several characters, both students and Iowa City locals, dance or write or dream or OnlyFans their way through the novel, each with a chapter dedicated to their point of view. There’s no central event or even issue that unites the stories, other than the fact that they’re all trying to figure out the meaning of life in the same college town. Taylor says he was striving to create as complex a narrative as he could, working toward “what Lionel Trilling calls moral realism, which is preserving the complexity of any given situation.” It’s not a portrait of a town, really. It’s a dozen looks at life that happen to intersect in one town, a “demimonde set in the Midwest,” he says. “It felt like it would have been a disservice to try to capture what themes I was trying to talk about, which have so much to do with community, and belonging, and the wages of expression versus non-self-expression. It would have felt like a disservice to those themes to only give it in one slice because the characters each have such particular perspectives and points of view.”

It’s not based on his life, but MFA programs are a world Taylor knows well. Taylor got his own MFA from the celebrated program. And that familiarity shines through but with the added benefit of showing more perspectives of the city over a longer period of time compared to his previous work, Real Life. “I wanted them to have many different kinds of problems that intersected with each other and didn’t intersect with each other, and I wanted it to feel a lot like my life felt at that time,” he says. “It felt like we were always tumbling into and out of each other’s apartments and porches and lives and talking about all of our problems.”

Taylor said he was only writing novels so that people would let him write short stories “in peace,” and he’s not usually one to pursue experimental formats in his own work. But he’s a fan of the way it’s turned out, and the process has helped Taylor expand his understanding of what makes a novel. “I realized that it actually does function as a novel,” he says. “And part of it was that I just needed to be less rigid about what a novel was in my mind.” But that doesn’t mean he’s going to be pushing boundaries further any time soon. “I’m fine with it in other people’s work,” he says. “But for myself, I’m like, no novels look a [certain] way, and they must look exactly that way,” Taylor says. “It changed my feeling about this one, but not novels [generally]. And I am still so rigid. I think there are rules. We need rules.”

I agree with him that rules are generative in writing, and it’s one of Taylor’s many opinions that send us both between laughter and serious musings on the nature of art. It’s a fun conversation, full of benignly provocative opinions that would spark debate only within a community who enjoy spending their time measuring the state of contemporary literature against the greats of the 19th century: Democratizing art is good, but that doesn’t mean all the art is good. “And that’s okay! We live in a free society,” Taylor says. “People should be able to make bad art!” The Sally Rooney bucket hats, though? Those were good. As is Sally Rooney’s writing. There’s a show I promised not to name that we both hate, even though all our friends and most reviewers seem to adore it. Taylor “really loved” Wharton’s The Custom of the Country when he read it recently but finds the “girlboss-fication of Undine Spragg,” the book’s antiheroine, “one of the media class’ strangest creations” (for more of his thoughts on this classic, check out the latest edition from Scribner, for which he wrote an introduction). What we settle on is that boundaries are good for art, but an inclusive, expressive society is more important than gatekeeping.

Plenty of the conversations in The Late Americans dig into much more exclusive views of art in an interesting way. The novel opens on a poetry workshop where Seamus, a jaded grad student, mulls on the garishness of forced identity and vulnerability in art, which is fitting as the first stirrings of the novel came to Taylor in one of his own graduate fiction workshops. “That felt like a period in the culture where things were getting quite identity-based,” Taylor says. “Identitarian rhetoric was really heating up in a kind of scary way. It started to feel a little overdetermined and puritanical. And I was looking around, thinking about how it was manifesting in my art and the arts of my peers.” A poetry workshop was just different enough from his own seminar, Taylor says, that he wasn’t worried about the critiques getting too bogged down in specifics. Though he does want to emphasize that the most obnoxious lines in the fictional workshop were fiction. “I was like, ‘What are some of the most annoying things to hear in a workshop,’ and I was going from there, but people who have read the book are like, ‘Man, this is eerily accurate.’”

The University of Iowa graduate programs these students attend are occasionally rarefied, sure. They talk about 16th century Russian paintings at their house parties and write poems about nuns. But graduate school isn’t easy for most of these students. A few of Taylor’s characters have enough money to focus on their studies, but most of them are working and living as cheaply as possible to get by. Seamus works in a hospice kitchen to pay rent. Ivan, an ex-dancer whose irreparable tendons pushed him into a graduate degree in finance instead of the arts, begins posting nude videos of himself to an OnlyFans-esque site to help provide for his parents, who made huge sacrifices for him. Fatima pulls shifts in a coffee shop and fights with other dancers in her program who insist that gatekeeping is good. “Oftentimes in the campus novel, when a character is having a hard time, it’s because ‘Oh, my secret pain, my secret sadness, I cannot discuss my dark family secrets,’” Taylor says. A couple of his characters feel guilty about inherited wealth, but none suffers, because they’re rich but not as rich as everyone else. “‘Oh, no, I don’t fit in with these people because they have yachts. But I’m also really rich and pretty and thin. Oh, no.’” But as usual, just because Taylor isn’t going to write that story doesn’t mean he doesn’t appreciate it. “Listen, I love to read that,” he says. “I do. I am an easy mark for some cozy, dark, academia.” But Taylor didn’t have the luxury of worrying about family secrets during his own studies. As an undergraduate, he once didn’t have enough money for soap. “So for a week, I had to bathe with laundry detergent,” he says. “Why is that not in any campus novel?”

Other protagonists aren’t graduate students at all. Fyodor works in a meatpacking facility, and Bea teaches swimming lessons. For a campus novel to turn its eye to its non-student residents is a refreshing move. “The fact of the matter is college towns, before they’re college towns, they are towns,” Taylor says. “And they’re optimistic places with economic and social diversity. And there are all kinds of people there who are making all kinds of decisions every day of their lives.” It’s perfect story fodder and the perfect antidote to the way “academia encourages or engenders a certain kind of provincialism,” he says. “That kind of isolation is not a function of geography but is a function of the culture of a campus. It is a provincial space because those people don’t think about people outside of the campus.”

Taylor also wanted to lean into the tension of choosing the financial disarray, real or perceived, that comes with grad school. Even for the characters who can afford to buy soap while getting their degrees, they have to face the idea that they’re somehow behind the rest of the country. “These are people who, to the outside world, are quote unquote grown-ups,” he says. “They’ve elected to come back for further education, but they are grown-ups. And there’s this horrible thing in American culture where if you’re, like, 25 and don’t have a house and a car, certain factions of this country don’t take you seriously.” This “obviously” isn’t true, Taylor says, “but that is what some people feel. So, writing about money felt crucial to the reality of these characters.” Part of these characters’ calculation is the pursuit of potential future prestige in dance or poetry, art forms that are losing some of the cultural capital they once held. One of Taylor’s struggles writing the book involved the fact that he hadn’t given his characters jobs in early drafts. Once he stopped avoiding that, “the whole book unlocked,” Taylor says.

So, reimagining his characters, dismantling his whole understanding of the novel, and a long period of time completely divorced from writing were all it took to bring us as many views as possible of life in Iowa City. Taylor even came to enjoy the experience of battling his own artistic rules. “It’s quite magical when your own art forces you to change your mind,” he says. “When you’re making the thing that refutes your strongly held beliefs, and you’re like, ‘How could this happen to me?’ as you’re doing it. It was a wild time, truly.” But Taylor’s crisis of craft conscience didn’t push him too far away from the books he likes to read. Assuming all goes to plan this time, Taylor’s own “capital-N novel,” filled with all the rules of the art form, will hit bookshelves soon.

Shelbi Polk is a Durham, North Carolina, based writer who just might read too much. Find her online at @shelbipolk on Twitter.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY