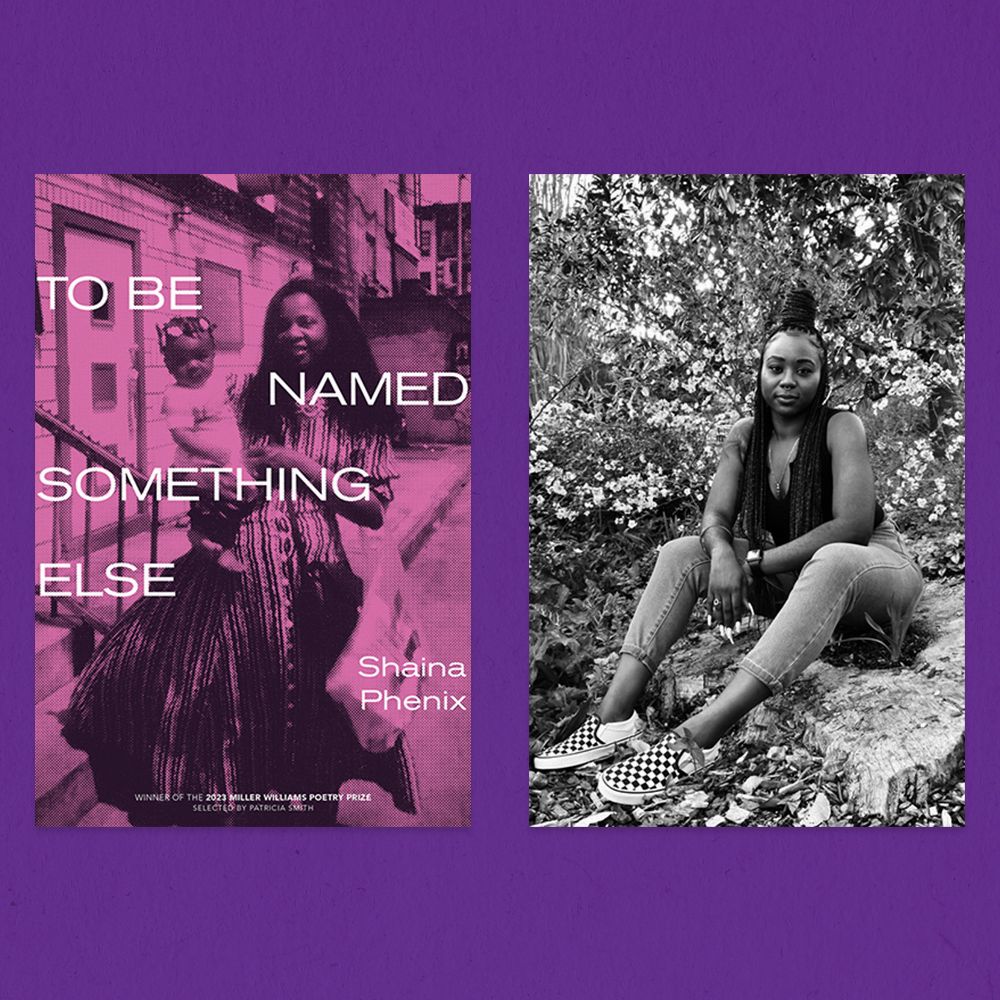

To Be Named Something Else, a new poetry collection from Shaina Phenix, touches on everything from the power of matriarchy to gentrification, happiness, violence, and lineage. It centers the coming of age of Black femmes and a love of Harlem that coalesce into a collection that balances pain and trauma with joy. Inspired by the women who raised her and an “obsession around maternal lineage,” Phenix wanted to “document those histories and celebrate them, and not make them ordinary but let them be [magical],” she says.

Currently working as an assistant professor of English at Elon University, Phenix is a queer Black poet and teacher from Harlem. Her work centers on Blackness, home, and the stories we pass down from generation to generation. To Be Named Something Else is her debut poetry collection.

Shondaland spoke with Phenix about why matriarchal lineage is so important to her work, how violence slips in and out of view, and watching your home change.

ARRIEL VINSON: Tell me about your inspiration for To Be Named Something Else.

SHAINA PHENIX: I guess for this, naming was really important, so inspiration is literally pulled from things that I could name. Be that lineage, be that materials from my childhood or childhoods that feel similar to mine, be that pieces of worlds that I wanted or that I imagine, and then pieces of worlds that do exist in my hands that are tangible and in my periphery.

The title actually came from what ended up being the title poem. I wrote the title poem, but I was calling the collection Wherever We Are, God Is or something like that. But I had a professor who was like, “People are going to think this is a book about religion. But there’s a lot of naming going on in the book, and you have this poem that literally is called ‘To Be Named Something Else.’ Why is this not the title of the book?” So when I got that feedback, I sat with it, and I was like, “This is literally a book of names, a book of ways of making and unmaking names that I’ve seen Black femmes, Black little girls be called and uncalled.”

AV: In this collection, you often cite your mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother, and one of the poems asks, “Who is responsible for the suffering of your mother?,” which I thought was such a great line. Why was lineage, especially maternal lineage, important to explore?

SP: I come from a long line of women who, for lack of better terms, had to figure s--t out. And in ways that, growing up, even when I didn’t understand them, felt like a kind of magic to me — the ways the women in my family made do, built things out of nothing, pulled together a bunch of scraps and built things for us to have, built lives for kids from lives that they didn’t even live themselves. I feel like that’s second nature to them.

I’ve never seen any women applauded or celebrated for those things. So, my obsession around maternal lineage just wants to document those histories and celebrate them and not make them ordinary, but let them be the magic that I found myself thinking. I also feel the most connected — spiritually, intellectually, all the ways — with the women in my family, and I don’t really look at the men in my family because they kind of lived in my periphery. Everyone who was in front of me were women.

AV: To Be Named Something Else also explores so many facets of Black womanhood. Some poems are about listening to Lil’ Kim and getting lip gloss, in some poems there are references to literary greats, and then there are also the experiences of sitting in a waiting room of an abortion clinic with other Black women. Tell me about womanhood being central to the collection.

SP: I started writing to understand something about pasts, which I learned over time I couldn’t understand without looking at what the past has laid out for how I exist now or how the women around me exist now. But looking at childhood and looking at the histories of people that I’m connected to also made me have to look at the nows of their lives, what becomes of them, what becomes of me, what becomes of us in their lives, which also informed how I was able to understand or pick apart the past. So, I went looking toward girlhood and realized that I couldn’t look toward girlhood without interrogating my understandings or experiences or the ways that I’m observing womanhood.

AV: And I thought that was so beautiful because in some poems, there’s a celebration. In other poems, it’s a declaration of “This is the pain we have to go through.” How did you maintain that balance?

SP: I don’t know if I intentionally maintained the balance. That’s just what felt true to me, to my understanding of my femmehood, was that there were the pains and the heaviness and the bags full of things that I, and we, are carrying. But I know there are some things — of pain, of trauma, of heavy — that I can’t look at without finding something of joy attached. Things don’t exist without each other, and that is the conundrum. The gel of Black femmehood is that this s--t can’t be separated.

AV: You also examine the violence against Black people, especially at the hands of the police. Some of the poems slip in and out of violence. You invoke names of those who have been killed, and some poems mention bullets when you least expect it. What did you want to say with the violence that’s present in To Be Named Something Else?

SP: It is always something that just is floating in, out, and around the everyday of us. And that feels important. I write, and I am always having this inevitable something, or the almost maybe of something, kind of over my shoulder all the time. And a lot of that was over my shoulder in the poems here. But the jumping in and out of harm, jumping in and out of images or trinkets of harm definitely come from the looming maybe of harm that I walk through the world with — that a lot of Black people walk through the world with.

From the poem “Harlem ’94-’04”:

The women say

amen, stomp their heels into the floor, squat. Thighs gaping, and tongues hang

from the colored lips. They rap as if Kim be kin or a god. When they leave,

they pile into taxi cabs for the club, us girls are in the mirrors — small

thighs gaping and kool-aid tongues hang from our lips, rapping, praying.

AV: As you said earlier, there are a lot of mentions of God and religion. The speaker mentions not quite aligning with the Baptist church and Christianity like her family does. How does a relationship with God, or the lack thereof, play a role in this collection?

SP: So much of it was me moving through what I now understand about the possibilities of God and the ways I’ve been blowing up what I’ve been taught to understand God as — the ways I’ve been navigating or placing my experiences and the experiences with people around me in line with the largeness of what God is.

I think about The Color Purple as my text. That was the first time I considered that God was everything and not in the way that we’re taught in church, that God is this “up here” being who created Jesus, who sent Jesus down to do the things, which I believe also. But The Color Purple and specifically Shug saying, “God is not some old man in the sky, but God is the tree, and God is the sidewalk, and God is the wind, and God is the old man who be drunk on a corner and make sure you get home. God is all these things.” And trying to find God in even the dark things — trying to find God in everything that I was observing — was in communication with trying to document the lineage.

AV: I love that. And in the collection, you refer to some things as a kind of prayer or ritual. I can’t remember the title of the poem, but there’s a poem where each stanza is a different letter of the alphabet, and you’re listing these things off. Even that felt like prayer or God or ritual.

SP: I think that’s “Alternate Names for Blood,” and most of the names are women who are a part of my family and sayings and, again, materials and trinkets and ways of understanding how we exist. I tried to put all of that in there. I’m building this as a live document for the launch, and I hope to make this a thing where people can add names, and add materials and trinkets and understandings, and make it as long as it can get.

AV: The collection is almost a love letter to Harlem too. I love “Breakfast Poem,” and it’s really about just how you order a bacon, egg, and cheese, but it’s also about the gentrification of the area. Tell me more about how you played with the joy of Harlem as well as examined what it’s becoming or what it has become.

SP: I did a lot of coming home as I was writing some of these poems and found myself walking up to things that in my mind, in my body, in my muscles, I knew what the place was but didn’t recognize. I found myself getting extremely observant. I would autopilot move through these 45 blocks. Like, “I know this is the park behind my old kindergarten, and this is the YMCA across the street from my high school, and this is the bodega that got the pork bacon, and I don’t eat pork no more, so now I’m going down to this bodega, who’s got beef bacon at least.”

Most of my life has been on autopilot. I didn’t know how to notice what was around me because it was in me or a part of me. So when I started to notice that I was not able to move through my home on autopilot — that I was seeing things that I had never seen before, that I was encountering people and ways of moving through spaces that I hadn’t before — I felt like, “I want to preserve and name my place, this thing that lives in me and that is changing outside of me.” So, the pieces of it that exist in me are still mine, but I’m also recognizing that in a few years we might not remember, or we might not have the bodega that only got pork bacon. We might not have the fish market where the old guy gives you free fish because he knows your mother is struggling. In three years, we might not have those things, and I need them to be somewhere. I need people to know they were there.

AV: Is there anything else about To Be Named Something Else that you want to talk about?

SP: So, the little snippets of the choreopoem [a type of poetry that combines music, dance, and song], where there are people who are named, are from a larger choreopoem. But every character, every name that is used here, is from some lineage of Black women who already exist. So, “Four Women” by Nina Simone are four of the characters. There’s Pecola Breedlove. There’s Fatou Gaye. I learned about her when I was studying abroad in Senegal, and they’ve made her the picture-perfect “what a wife is, what a wife does.” I was super-interested in giving her a voice. Because, maybe not in the same context, when I was doing the interviews to compile the information to fill these characters with the women I was speaking to, there were so many Fatou Gaye-like stories where women are like, “I was told here’s how I exist, here’s how I show up, here’s the best way to be loved and to be held.” So, the choreopoem pieces definitely are all timeless lineage, are all putting together words and ideas and imaginations of some of the people that I love and that I’m always writing and thinking in homage with. Just letting people that I know, people that I’ve encountered be in communication with those lineages and see what happens with them.

AV: What are you working on now?

SP: I have a second collection of poems that lives in this imagined underwater space. So, the last poems in To Be Named Something Else are actually some of the first poems in the next book. I’m imagining a world that was created at the floor of the Atlantic Ocean from West African folks who were meant for enslavement, who thought they were going to die by jumping off ships, but get in covenant with the fish. There’s basically a Black heaven that is at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. And it’s doing some of what the choreopoem is doing, but blowing it up by trying to figure out how to play with making people who have been murdered or passed on have lives that they didn’t have.

It looks at them doing what feels mundane and normal. So, I have a poem in which Tamir Rice goes to get a haircut, a poem in which Harriet Tubman and Henrietta Lacks run a clinic. George Stinney Jr. actually has electricity in his hands and helps people around this underwater world, and he’s allowed to go to Earth. So, I’m just playing around, trying to do this world-building thing.

Arriel Vinson is a Tin House workshop alumna and Hoosier. She earned her MFA in Fiction from Sarah Lawrence College and received a B.A. in Journalism from Indiana University. Her poetry, fiction, and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Catapult, Booth, Cosmonauts Avenue, Waxwing, Electric Literature, and others. She is a 2019 Kimbilio Fellow. She tweets at @arriwrites.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY