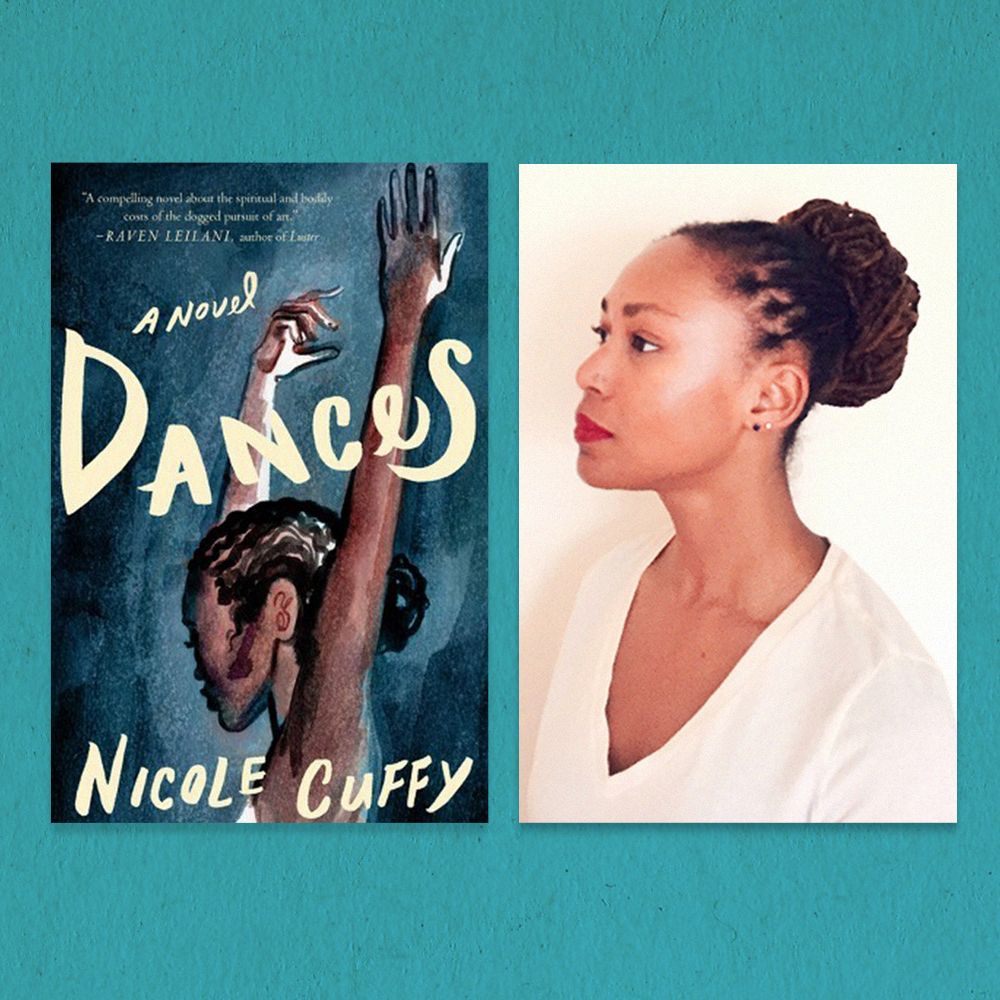

Nicole Cuffy’s debut novel, Dances, follows Cece, a 22-year-old Black ballerina at the height of her career who was inspired by her older brother, a visual artist, to begin dancing as a child. But when she becomes the first Black principal of the New York City Ballet, she can’t help but be tormented by her brother’s disappearance and the fact that she feels like she doesn’t belong. Cece eventually understands she has to confront her complicated past in order to forge forward. Dances is about Black girlhood and womanhood, pursuing art, grappling with the addiction of a loved one, and learning to define what freedom looks like.

Cuffy is an author based in Washington, D.C., and currently lectures at the University of Maryland and American University. She’s the author of the chapbook Atlas of the Body that won the Chautauqua Janus Prize, which "celebrates an emerging writer’s single work of short fiction or nonfiction for daring formal and aesthetic innovations that upset and reorder readers’ imaginations."

Shondaland spoke with Cuffy about the impact family has on your career, impostor syndrome, and what it means to be a muse.

ARRIEL VINSON: I love that artists of all kinds are starting to confront, in novel form, how beautiful but exhausting it is to pursue art. What was the inspiration for this novel?

NICOLE CUFFY: I think the novel was conceived out of a space of me wanting to read a novel like this. I wanted to talk about Black women in art spaces, specifically ballet and the classical-neoclassical ballet world, and I didn’t really see any novels specifically touching on the subject. I thought the only way that I could explore it the way that I wanted to was to write it myself.

AV: And you’re a dancer too?

NC: I am a dancer in the sense that I dance. I was never a professional ballerina, but I do love ballet. I love the art form. I go to the ballet really frequently. I take ballet classes, but I don’t perform.

AV: There’s a lot of tension in Dances between Cece’s mother and her career. Her mom is dismissive of her dancing even as a child and tells her it’s not practical to pursue it. Why was this complex relationship important to the story?

NC: It could be potentially easy to read Cece’s mother as not supportive, but the way that I see her and the way that I understand her is she’s terrified. She is a culturally traditional Black mother who is trying to prepare her children for a hostile world. She sees dance or art as very risky for her children. In fact, for one of her children, it doesn’t save him. So, I think she’s trying to save her daughter by being critical or hesitant to accept her chosen career path. For me, that’s important for the plot because it’s one of the ways in which Cece is in two worlds.

She’s in this very culturally Black world. She’s from Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn, but at the same time, she’s also immersed in this very traditionally white world, which is the world of classical and neoclassical ballet. She’s constantly walking that line and perhaps in some situations even being asked to choose which identity she’s going to perform publicly. That’s one of her central struggles here.

AV: While this is a story about being a dancer, it’s also a story about her brother and how he’s the inspiration for her dancing career. Because of his addiction, he’s disappeared, but on each page we feel her longing and abandonment. Tell me more about exploring this relationship.

NC: When it comes to Cece’s brother, I was trying to explore the idea of how museship works. I thought of it as more of a symbiotic relationship where they’re a mutual inspiration to each other — the muse gets something for being a muse. Cece sort of acts as a muse for her brother. She appears in his art; he draws her a lot. He is constantly exploring her form. In doing so and being so interested in her as an artistic inspiration, it fosters her own interest in another art form. Even as he’s disappeared, he acts as this kind of ghost motivator for her over the course of her career. Even when she attempts to find him, he remains a phantom muse.

She’s got one form of support from her mother that doesn’t feel like support, but then she’s got another kind of support from her brother that does feel like the kind of support she wants. I’m always interested in the relationship between siblings because you have people who really don’t ask to be put together, and a lot of it is a crapshoot of how much they’re going to get along. Even if they don’t get along with each other, there’s sibling love underneath the surface that I think is fascinating. It’s very different from parental love and different from a friendship kind of love but is so strong and deeply rooted.

AV: Dances also examines Blackness in dance. Cece is hyper-aware of her body. She constantly doubts her ability because she’s learned that she has to work so hard. How does body image play a role in this novel?

NC: I can’t talk about dance without talking about body image, especially if I’m talking about a dancer who is minority in some way, because classical and neoclassical ballet still very much places the emphasis on uniformity and conformity. If you have a body that by default does not conform to the traditional aesthetics of classical ballet, you are hyper-aware of it, and it would feel very uncomfortable for you. The ballet world is only just now starting to look at that more critically, but by the time that Cece has reached the pinnacle of her career, unfortunately she would’ve spent the majority of her life as a dancer in a very hostile space for a Black female body. I say Black female body very deliberately because the trajectory for Black men in dance has been very, very different. Not that there hasn’t been struggle with male Black bodies in dance, but it’s only very recently that we are seeing Black women centered on classic-neoclassical stages. Ballet is an art form that demands nearly impossible things of the body, whatever that body looks like. It requires this hyper-focus on the body, what it weighs, what it looks like, what it does.

But if you have a Black body and you’re constantly told that that body is not classical, that it’s not pretty or delicate enough to play Aurora in Sleeping Beauty, or to play Odette/Odile in Swan Lake, then it would be pretty much impossible for you to be in this world and not constantly be self-conscious of your body, and trying to find ways to make it beautiful and delicate in the eyes of what unfortunately is still a predominantly white audience and a predominantly white institution.

AV: Cece also experiences impostor syndrome. Outside of her being a perfectionist, she’s the first Black principal of the New York City Ballet. Tell me more about Cece’s struggles.

NC: This is something that is such a universal experience for Black professionals in almost any medium because we live in a society that was founded on white supremacist principles. A couple years ago, I started teaching a class on social media and discourse, and the kids are all on TikTok, so I was like, “Well, let me join TikTok too to see what these kids are seeing.” I remember seeing one video of a sociologist saying that what you’re feeling is not impostor syndrome because you are an impostor. The spaces you’re breaking in to were not meant for you; you were not meant to succeed in these spaces.

I don’t think this is an exclusively Black experience. I think lots of people who enter into the upper echelons of their career trajectories experience impostor syndrome, but I think it is a uniquely minority experience — that impostor syndrome contains a grain of truth that you weren’t meant to get to where you’ve gotten to. In the case of Cece, that’s certainly true. We can talk a lot about classical and neoclassical ballet companies internationally, but Balanchine is the father of American classical ballet, and New York City Ballet is Balanchine’s baby. He, in particular, valued these tall, willowy, white female bodies. So this was not a space that was designed for Black women to succeed in.

I very deliberately made her a brown woman with 4C hair. She wasn’t going to be light skinned, she wasn’t going to have the kind of Blackness that white people are most comfortable with because of its proximity to whiteness, so should Cece or a woman who looks like her be promoted to the role of principal in a company like the New York City Ballet, there would be some discomfort in white audiences with that.

There’s resistance from the audience, from people who are staging these ballets, from artistic directors to really have a critical look at the inherent racism in the ballet world. So, we’re having these conversations now. Misty Copeland’s promotion was a huge catalyst for upping these types of conversations, and that’s good, but it is very much moving at a pace that white people are comfortable with, which means these changes are happening very, very slowly.

AV: We see fetishization in Cece and Kaz’s relationship. Even though Kaz is her mentor, he also looks at her, as Cece says, in a way that is not completely like a daughter or mentee.

NC: This is another conversation that we’ve been having in recent years about the dance world — the very complicated relationship between these artistic directors and their often-young ballet staff. I loosely modeled Kaz off of Balanchine himself, since Balanchine famously used his company as his harem. He selected his partner from his staff, and he would be inspired by one of these young ballerinas one minute, and the next minute would move on to another very young ballerina who would be his inspiration, who he’d make ballets on. Kaz is not nearly as predatory as that. He never puts Cece in a situation where she feels she has to enter into a romantic relationship with him, and when she tells him, albeit indirectly, that “No, we’re not doing this,” he says okay. He’s also not serially selecting his partners from the ballet company, at least not that we see on the page.

There is this interestingly complicated relationship between ballet student and ballet teacher, or ballet dancer and their boss/the artistic director, where again you have someone who is very focused on your body. I mean, in my ballet classes, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had a ballet instructor touch me on my butt or something to correct my position. It’s not remotely sexual, but it’s interesting because it’s a different kind of boundary in that space that wouldn’t necessarily work that way for anybody else. I can’t think of anybody else I would allow to touch me like that.

But there is something clinical about the relationship between an artistic director’s hands and their dancers’ bodies. I thought it was also very interesting to explore how that boundary can get a little bit blurry sometimes, and it does with Kaz in particular. He’s literally watched Cece grow up, and yet he has this not quite fatherly attraction to her that she eventually does have to shut down.

AV: I also want to talk about her relationships with other dancers. We have Ryn, who’s her best friend, and Cece always, at least in her head, says, “Ryn’s so talented; she should have this part.” Then there’s her relationship with Irine, where she’s trying to recruit Cece to her company. Why did you examine these relationships between dancers, and why do you think it was important for Cece’s growth?

NC: I thought it was important because of how a ballet company works. Because you’re spending so much time with these other dancers, and you have this intimacy with them — you’re doing something really hard, but you’re doing it together — it makes for very interesting friendships, and it also makes for very interesting not quite friendships. Cece is not quite friends with some of the dancers that she works with, but there is still intimacy. I thought that that was so interesting in terms of how you move forward, and I also wanted to illustrate a different kind of ballet story. The stereotypical ballet story is, frankly, a little bit misogynistic, where you have these female dancers who are out to get each other, putting glass in the pointe shoes.

Not only is that not accurate, that’s just not how dancers relate to each other. If they’re in the same company, they want the company to succeed because that’s how everybody gets paid. So, it was important for me to illustrate female friendships that weren’t about being catty and weren’t about these betrayals.

I wanted to disrupt that narrative. It was important for me to illustrate what female friendships can look like in this setting. That’s not to say that the ballet world isn’t incredibly competitive. It absolutely is, but that doesn’t mean that nobody can get along or that people are trying to sabotage each other. I really wanted to explore that, and I tried to do that with Cece’s sister-like relationship with Ryn. Then I have Irine, the dancer who didn’t quite make it the way that she wanted to. She didn’t get to stay in the School of American Ballet. She didn’t get to advance on to the company. How do we maintain a friendship like that when we’re living in this very insular world? Irine drops off the face of the Earth, but then she returns, and there’s this joy that Cece has at seeing her, but there’s also an illustration of a different trajectory.

It was also important for Cece to see this because it forces her to make a choice. She doesn’t have to stay with the New York City Ballet. There’s another option. She can go somewhere where she might feel more accepted and more where diversity might be more meaningfully explored, or she can stay in this very white neoclassical world and fight her way through it.

Arriel Vinson is a Tin House workshop alumna and Hoosier. She earned her MFA in Fiction from Sarah Lawrence College and received a B.A. in Journalism from Indiana University. Her poetry, fiction, and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Catapult, Booth, Cosmonauts Avenue, Waxwing, Electric Literature, and others. She is a 2019 Kimbilio Fellow. She tweets at @arriwrites.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY