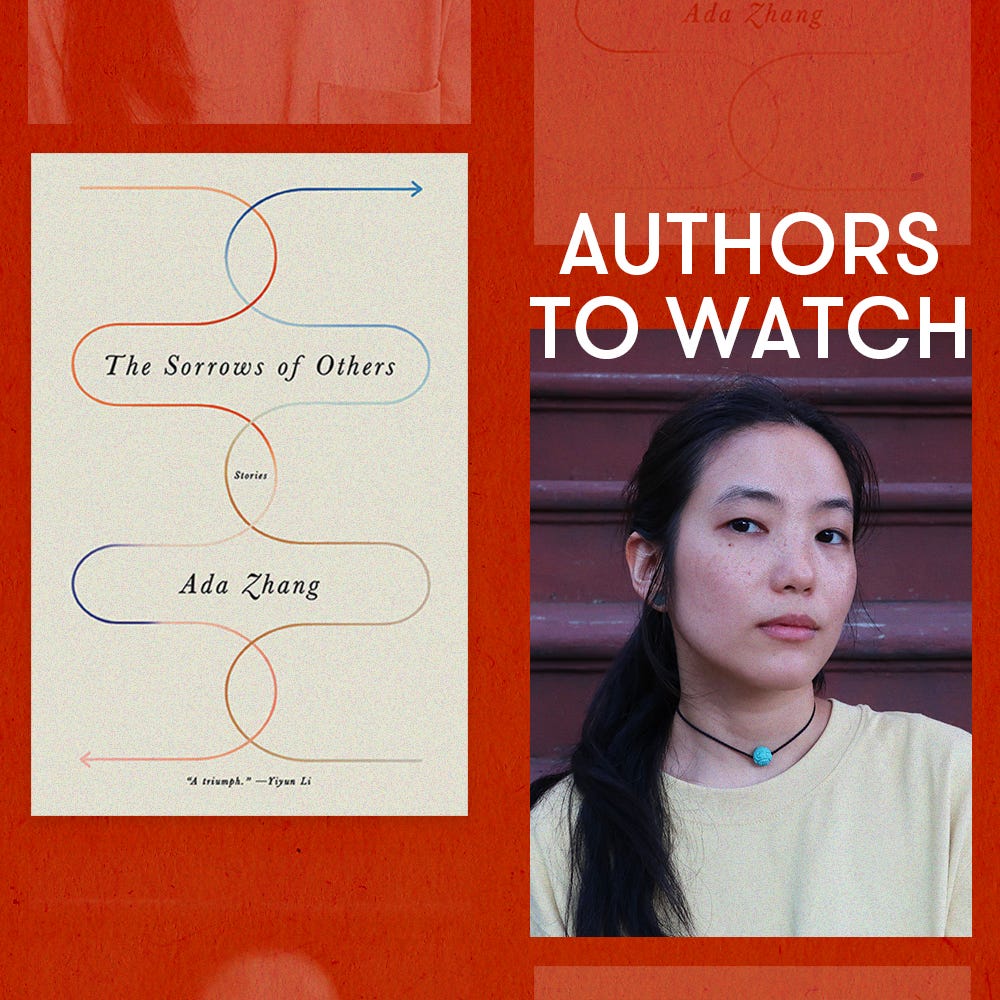

“The Subject,” the brief opening story of Ada Zhang’s debut story collection, The Sorrows of Others, follows a college student rooming with an elderly Chinese woman who picks up trash in the neighborhood even in winter. The narrator hopes to make the woman the subject of a school project, but their communication and relationship don’t unfold as she had planned. It’s a story that captures the heart of the collection in which everyday living and relationships glimmer in their honesty and nuance.

Many of the characters grapple with loneliness and loss and grief and joy in simultaneous measure, which was essential to Zhang as she set out to write. Some are older and have lived through the terror and complete destruction of the Cultural Revolution, the communist movement in China led by Mao Zedong from 1966 to 1976, and Zhang’s interest lies in, as she puts it, “the living on” after these historic moments in time. Immigration, intergenerational relationships, and the many iterations of love carry the characters through their lives as they experience journeys of all kinds, and the result is a slim volume of stories that are unforgettable.

Zhang, an editor at Running Press (an imprint of Hachette based in New York City), is a graduate of the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her writing has also been featured in McSweeney’s, A Public Space, and more. Shondaland spoke with Zhang about the meaning of “other,” loneliness, intergenerational communication, grief and joy, and beauty as a teacher.

SARAH NEILSON: How did these stories coalesce for you? What was the journey of putting this collection together?

ADA ZHANG: I wrote one story in 2015 when I was working a full-time job, and then I wrote another story. I couldn’t really seem to stop, and so I decided to commit myself to it fully. That’s when I went to my MFA program, which gave me a lot of time to write many more stories. In 2020, around the time the pandemic started, I had all this time. I had just finished the program, and there was nothing else to do, and I was unemployed at the time, so I just worked on all the stories. But even then, I did not think it was a collection basically until my agent said, “This is a collection!” That was the moment I put all the stories together in a Word document; then I really thought of it as a collection. That was very exciting because then you can revise the work as a collection. It’s really thrilling to work on each of the stories on their own terms, and then to put them together and see how they speak to each other. It’s the part of the process that I did not anticipate because it’s a little bit mysterious, but it was very thrilling to really see them together just side by side. I think of them as friends.

SN: The title of the collection, The Sorrows of Others, got me thinking about the word “other.” What does that word mean to you and to your characters? How does it speak to a distance between people?

AZ: I think in a way we are all others to each other. On the very small micro level, each of us is alone, and everyone else is an other. And I think everybody in their own way has had that feeling of being an other. Just feeling outside of something — it can be anything; even not getting invited to a party can make you feel like an other, or not having the clothes that everybody else has. But I think what is so interesting about being made to feel like an other is that somehow by being othered, you are really able to see that thing that you’re outside of. You can see what it is because you’re not part of it. You have a point of view on the inner circle that the inner circle does not have, even if that inner circle is just one other person that you’re trying to be close to. We are all others to each other; existing in society raises a lot of questions about who is the other. Many of the characters in my stories are immigrants or the children of immigrants, so they’re operating from that margin and able to sort of see their setting in a way that perhaps people who are native to the place can’t. And in that same way, being an immigrant is also interesting because then you also develop a point of view on the place that you left that you’re no longer a part of. So, I think immigrants in this country have a really complicated relationship with this idea of being the other. Again, it’s something I think everybody has felt before. I think the feeling of being otherly is pretty essential to being a person. I think it accounts for a lot of our loneliness. But I think that is amplified for marginalized people and people whose lives don’t fit in to whatever the mainstream convention is.

SN: How were you thinking about loneliness, and how did you approach rendering it for the different characters while you were working on this collection?

AZ: Yeah, there’s lots of lonely people in this collection. Again, I think it’s just part of living. We have to learn to live with loneliness, and one of the rude awakenings of becoming an adult is that you have to cheer yourself up and love yourself and be your own company. But also, there’s so much richness and wonder to be had among other people, and seeking that out is also what life is about — finding a community, finding friendship, finding connections. I think my characters struggle with that a lot. They’re very protective of their solitude, and I think it’s a measure that they take so that their loneliness belongs to them. It feels doubly lonely when your loneliness is caused by someone else. And in a way, loneliness is my emotional obsession, and me writing these stories is my way of seeking some bit of understanding of what this is. What is loneliness? Why do we feel it? And why is it such a part of life? I put my characters into situations where they either choose to be alone or they seek company, or they withhold their company from others, whatever it is. Writing is one of the only ways I know to ask these questions, to let the stories really do the asking and let the characters figure it out.

SN: What drew you to writing intergenerational relationships and the communication that happens, or doesn’t happen, between generations? What felt important to explore about that, especially for immigrants?

AZ: There are so many obstacles to human connection all the time, and generation is one of them. It’s hard to speak across generations; every generation experiences it. There’s the friction between parents and their kids, and it’s just a tale as old as time — kids not wanting to listen to their parents who are not understanding, or parents who are not understanding their kids — it never goes away. And I think that barrier and others like it are part of what keeps us away from each other. But my characters really try to speak through that barrier and to know each other. Whether or not they actually do, that’s for the reader to decide, I suppose. But I think that seeking to know another person across a generation or across place and time, I think that’s valuable in and of itself. That seeking, even if nothing conclusive is reached, is still meaningful — to try and understand and to be understood. So, I think the generational aspect of my stories highlights the desire to connect and the inability to connect.

SN: It’s so nuanced. Like that first story, where the young narrator is roommates with an older woman, and there’s a lot of misunderstanding between them, and there’s some negative emotion around it, but they’re still connecting in a way.

AZ: Yeah, totally! They’re not connecting in the way that perhaps the young narrator fantasizes. But there is something honest about their connection.

SN: Along those lines, can you talk a little bit about age and aging in the book, how you were thinking about that while you were writing, and maybe how that plays into this undercurrent of the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath that is in a lot of the stories?

AZ: I love to think about aging. Personally, I’ve really enjoyed getting older. There’s this idea of coming of age being for young people, but I think that’s false. I think people are coming of age all the time. And it’s kind of amazing the revelations and insights that older people come to about their life at later stages. In some ways, some of the stories could be read as older coming-of-age stories.

I love to think about time in fiction. I think what’s tricky about working with a moment in history is that you really don’t want that person, the character, to be defined by that moment in history. There are so many circumstances outside of our control. And the Cultural Revolution was a big, huge moment in China’s history, and it’s one that affected everyone’s life in some way. Nobody was unaffected by this. But I am always interested in the part of the story, any story, that returns to daily living. What is truly remarkable to me is not the fact that someone lived through the Cultural Revolution, but that they kept living on after it and after it and after it. For a lot of these characters, that happened, that was part of their life, and then they had so much life after that. After the big moment, the big historical moment, the living on is really what I’m interested in.

SN: How does that tie in with agency, and how were you thinking about agency and subjectivity while you were creating these characters and these stories?

AZ: I was about to use the word agency. It’s hard because when these big historical events happen to us, it does actually feel like we don’t have agency. And in a lot of ways, we don’t. But we always have a point of view, and I think that is enough agency. We can say what we want about it, and that’s agency. Even if we can’t do anything, even if we’re trapped, we have our inner lives, and that’s ours. So, it was important to me that even though there were things outside of my characters’ control, that they still had their own desires and their own whims, and weirdness and tastes and attitudes that are just theirs, that belong to them. So even if they aren’t able to change their situation, they are still people in their situation.

SN: In one of the stories, the characters talk about dreams versus expectations. Can you expand on the ideas of dreams and expectations in the book?

AZ: Dreams and expectations can be at great odds with one another sometimes, and I think everyone is always doing a balancing act between what we want, what we dream about or hope for, and what needs our attention, what is absolutely necessary. I don’t think that dreaming is something that only people in seats of privilege are allowed to have; I think everyone has dreams, and everyone has expectations. All of the stories can be read as a character figuring out what that balance is in their life. In the last story, “Compromise,” the main character had an affair years ago — a real love — and she gave that up to fulfill an expectation. I think we all have really unique and personal relationships to our dreams and our expectations.

SN: How did you approach exploring or rendering loss, grief, and death for these characters?

AZ: I’m a little baby, and I’m scared of everything. Like, I’m scared of every little pain or uncomfortable feeling. I lose my mind. But one of the things that I learned through writing these stories, and that I felt was important to show, is that loss and pain and grief really start from happiness and love. Which sucks! Because it means that if you want to live a rich and meaningful life, you’ve got to be prepared. For me, it’s about remembering that joy and happiness and love are actually where grief comes from. You have to give your characters something to lose if the loss is going to be felt. I think that was my personal approach to grief and loss. [Joy and grief] are like the same thing. In moments when I felt great love, it felt close to sadness. And when I’ve felt serious grief, there’s almost a weird elation also. It’s such a profound feeling.

SN: Speaking of joy, where are you finding joy or creative inspiration or even just rest right now?

AZ: I’ve loved seeing the spring blooms, the cherry blossoms and pear trees and the crab apples and the smelly trees that are all just blooming and littering the floor with petals. I’ve tried to go outside as much as I can to see spring in action. I don’t always do that. Basically, beauty has been a great influence to me, so I have been trying to just look everywhere.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sarah Neilson is a freelance culture writer and interviewer whose work regularly appears in The Seattle Times, Them, and Shondaland, among other outlets. They are an alum of the Tin House craft intensive, and their memoir writing has been published in Catapult and Ligeia.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY