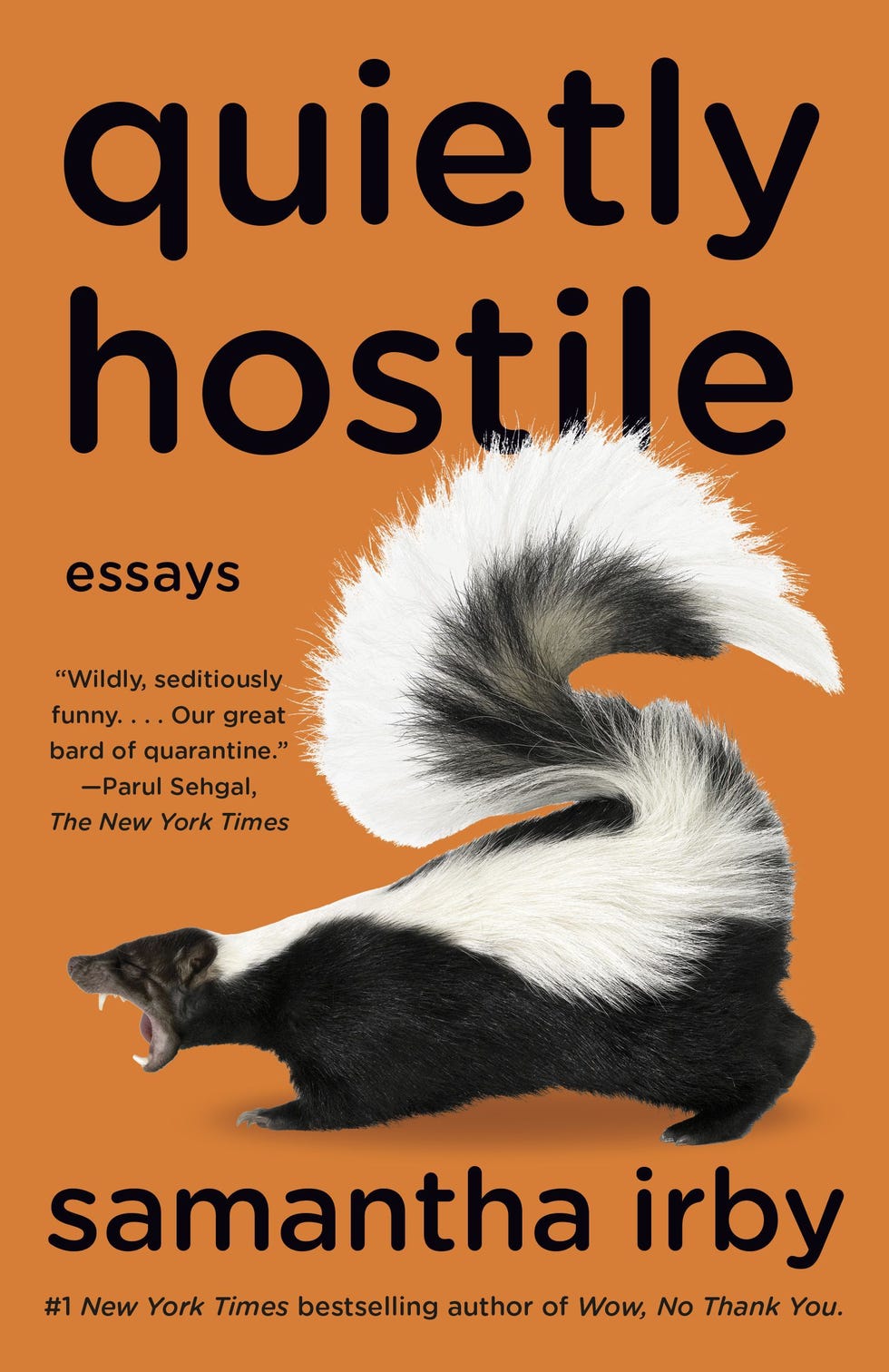

Few writers can scrounge up the authenticity to write in their actual human voice, let alone embody that voice consistently across both life and the ever-increasing multitude of platforms to which a writer can contribute. But with Samantha Irby, the voice you read is precisely the voice you hear when you meet her. In conversation and within the pages of her three best-selling essay collections — Meaty; We Are Never Meeting in Real Life; and Wow, No Thank You; as well as the freshly released Quietly Hostile — the Chicago-born Michigan transplant infectiously revels in the absurd, laughing at her own foibles as she cheekily ruminates upon navigating the things we all care about: life, love, and the pursuit of a clean toilet. Irby is also a hot hired gun in the TV world these days, injecting her hilarious bon mots into scripts for And Just Like That … (a new season is forthcoming in June) and all three seasons of Aidy Bryant’s Shrill.

Reading Irby’s work is like you’re belly up at a bar, shooting the s--t and peeling off the layers of your humanity with a hilarious confidant in a judgment-free zone — even though you’ve known her for all of 10 minutes. Speaking with her is no different. Soon after saying hello, we joked that our conversation would become something of a therapy session, and indeed, with her warm openness, charming and disarming honesty, and lack of guile, we were opening up to each other in no time.

As with Irby’s prior volumes, her latest book, Quietly Hostile, takes us through the light and the messy, from scary allergic reactions to sex-play recollections to (literally) explosive fecal matters (she suffers from Crohn’s disease), interspersed with almost court-worthy defense cases for her oft-disparaged basic passions, like Cheesecake Factory and Dave Matthews. She metaphorically hurls an anvil at the very idea that her success has turned her highbrow. She simply is a person, among us, in the world. She’s just figured out how to chronicle her experience and get paid for it.

We caught up with Irby, who was in the midst of her book’s release and the upcoming second season of And Just Like That, and got her hilariously illuminating insights on everything from how she decides what to write about to what she definitely won’t write about, to surviving Hollywood development hell.

VIVIAN MANNING-SCHAFFEL: Do you prefer Sam or Samantha?

SAMANTHA IRBY: Please call me Sam! When I was a kid, because my dad’s name was Sam, I hated being called Sam. But now he’s dead, and everyone calls me Sam [laughs]. I was like, “Goodbye, only other Sam Irby!” At this point, if someone calls me Samantha, I get the IRS shiver: Is my mortgage late? It’s like when your mom walks into your classroom at school, and you’re like, “Guh!”

VMS: You dedicated Quietly Hostile to Zoloft. Can we attribute that to “quietly”?

SI: [Laughs] I wish! It’s definitely tamped down some of the hostility, for sure. This is a wild thing considering I have a book coming out that doesn’t mention it, but I just got diagnosed a year ago with OCD — that’s what I’m on Zoloft for. I am not up to the full therapeutic dose, but I’m definitely feeling its effects. This book? Not Zoloft written, though I thanked it. The next book will be my full mentally well Zoloft book.

VMS: Because of the tone of your writing, do people come up to you because they feel as if they know you and share all kinds of things? They must feel so comfortable with you from the outset.

SI: Yes. I’ve had readings where people bring me their favorite kind of toilet paper or their favorite recipe for clogging themselves back up if they’ve had a few days of diarrhea. It’s not just my intense need to be liked that makes me open to it. Even if we’re sitting next to each other in a waiting room at the doctor’s office, if we’re going to talk, I don’t want you to be like, “It’s so cold out today.” Anything below the surface … I love when people feel like kindred butthole spirits! One of my friends, who’s a chef, got an early copy of the book, and she was like, “Oh, my God, that reminds me I meant to tell you I s--t my pants in the car last week,” and I was like, that’s what I want to know! Yes, people are extremely forthcoming, and I love it.

VMS: Thank you for your service because this is important. You also have that bartender vibe. It’s so rewarding to have the most intimate conversation with someone on a train in, like, two stops.

SI: And then get up, walk away, they’ve impacted your life, and you never have to see them again. You don’t have to worry about what their favorite foods are. You just have a real honest moment with a person. I love that! I welcome that. Honestly, the pandemic has robbed me of that because Wow, No Thank You came out in 2020. I didn’t tour. I did some virtual stuff — which is incredible that we have this technology — but it’s not hugging a person. I missed this divulging of intimate secrets with strangers. So, I’m excited to hear people’s stories again.

VMS: When it comes to your own stories, how do you land on what to include in book drafts and what doesn’t make the cut?

SI: This is a good question. First of all, there are some things that happen that as they’re happening, I’m like, okay! Thank God! This is a thing I can write about. The anaphylactic shock [in the new book], I’m like, if I live, this is going to be an amazing story. I knew I was going to live — I’m just being dramatic — but truly it was like a horrible thing is happening, it’s also hilarious, it also is new, that’s going in. So, some things, even as they’re happening to me, I’m like, can’t wait to process the s--t out of this!

I always try to have a variety of subjects, and with the last book, my editor was like, there’s not enough gross sex stuff! So, I try to cover some bases. I try to think about what fans of my writing, or people who know about my life, want to hear about. They want to hear about my stepchildren or my journey — gross — as a stepparent, but I can’t write specifically about the kids because they’re underage, they’re not my kids, they’re hands-off.

Everybody knows I have a dog, so I have to write about the dog. Everybody knows I wrote on And Just Like That, so I have to write about that. That’s still my job, and I’m not trying to piss off Carrie Bradshaw, so I’m like, how can I write about this in a way that satisfies people who wanted me to write about it but also doesn’t get me sued by HBO because I broke my NDA? QVC — I’m tuning in to Isaac Mizrahi Live; I’m going to write about how much I love QVC. I do get stoned every night and pretend I’m on a raft surrounded by whales; I’m going to write about that. I’m at this point where I can put whatever the f--k I want in a book, so I’m like, I want to write a love letter to Dave Matthews in the book and have the world read it.

VMS: We’re going to touch on some of these things specifically in a minute, but do you have, like, a writing community or friends whom you bounce stuff off of? Or your wife?

SI: Never to my wife. Here’s the thing: I guess here’s where I’m self-protective. I can’t have anyone else’s opinion in my brain before a thing is done. I cannot write knowing that someone might be like, this isn’t as funny as you would think. I can’t work like that. I have a writing partner, Ian, who I have written with for a long time, who edits me. I will send him things after they are completed. This dude is super-smart, he reads, and he’s an incredible writer. He only tells me things that will make the work better, which I appreciate, but also I don’t want to hear what regular people think about my work. You might have an English degree, but if you didn’t write a book or do any sort of professional writing, you can just read it when it’s out.

I do so much writing in my head, I don’t ever need to work out how things should go with anyone other than myself because almost everyone gets in my head, and I want to scrap it. I never hate my own work until someone else sprinkles a little salt on it. I’m the kind of person that, a couple of weeks ago I was recording the audiobook — copies are officially finished — and while I was recording, I was like, that’s a clunky joke. I should change that. I would literally never stop tinkering, so I just have to reach a point where I’m done, send it to my editor, and that’s it.

VMS: What’s the most surprising thing you learned about your writing between Meaty and Quietly Hostile?

SI: I honestly continue to be amazed that my work resonates with actual people, you know what I mean? Not because I’m so f--king special, but people have hung in there with me all this time, and it feels like a good community. I’ve never met anyone who likes my stuff who I was like, I feel like you’re a bad person. I feel very lucky that people continue to be interested in whatever I’m saying. Particularly since I’m not saying a whole lot of explicit stuff about the world at large — it’s pretty much my world — and that people have continued to hang in there is the biggest, extremely pleasant surprise.

VMS: Your work is so personal, it’s rare that you’re going to attract someone who is not with you.

SI: I understand what I do. It’s so funny; every time book award season comes around, my writer friends and I joke about who’s going to be nominated the least, and I’m like, oh, it’s always me, because I write jokes, and everyone thinks they can write jokes, so they automatically discount what I do. Essays — truly, everyone thinks they can do that, as you can tell from the explosion of essay collections. Then you add on the cursing and the pissing and s--tting and vomiting — I know what I do, and I know who appreciates my work. I know there won’t be any gold emblems stuck on the front of my books, and it’s fine. Considering it’s not widely appealing, I’m super-stoked and grateful that my stuff continues to find people who like it.

VMS: You always say you didn’t go to college — high five. The publishing world can be elitist. What advice would you give to anyone who feels intimidated about just starting to write on their own?

SI: My anxiety about not going to college stems from going to a high school where a lot of my peers went to big, amazing schools, and also because mine was taken from me by my parents’ decisions to be old and pass away and leave me with no safety net, so I have a hang-up about that, but I am a testament of, if nothing else, you don’t need to go to Iowa to have a writing career that is successful. Maybe you do if you want to get this award or get on this list, but you don’t have to if you want to get your work out into the world. I’ve sold 350,000 books, and I also don’t have college debt. I also don’t know a lot of these writers that writer-y people reference, but I don’t think you have to, and not just because I didn’t. I have a lot of writer friends who are successful who are making the things they want to make and who don’t get bogged down by the accolades they don’t have. There’s no permission door. Some people will gate-keep — that’s the nature of s--tty people. They’ll be like, “You didn’t go to whatever program or have whatever kind of degree” — those aren’t your people. I care about: I have my check now; what do I have to do to get another check? I do not get caught up in the people of it all. That’s advice I would give. If you need a community, you certainly don’t need a toxic one, so I would say anyone who’s rude to you or weird, you don’t need them. I’m on good terms with a lot of writers, none of whom I talk about writing with. We’re just friends who talk about friend things. I can’t imagine being in a universe where everything is like, did you see who’s on Publishers Marketplace today? If that makes you happy, it’s all good, but you don’t need to participate in it to have a writing career.

VMS: I’ve noticed every one of your books has kind of a rhythm to it. There’s always a gut punch of an essay — like in Quietly Hostile’s “Oh Brother Where Art Thou?” — that’s emotional and deep. The essay after that is usually a hilarious recovery. How do you decide what to share? Is there anything in your life that’s off-limits? What’s your litmus?

SI: I do keep some things inside. If I have a personal beef with a specific person, I tend not to write pieces like that because they’re written in stone, and it’s pretty hard to walk it back. Things that may cause real strife between me and a person who I actually continue to care for and may want around, I just don’t. An old boyfriend hit me up after Wow, No Thank You came out, and I was like, “Yeah, man, you f--ked up, and I wrote about it. I didn’t say your name. If you used context clues to figure out that was you, that’s on you.” This is my general rule: If I wouldn’t want it on the news, I don’t put it in a book because, essentially, I’m going to spend the rest of my professional life putting myself in situations where someone can ask me about that. You have to be prepared to have insensitive people hurl your words back at you. I’m not going to be at a reading or in an interview and talking about like, I know I wrote that, but it’s off-limits. Anything I wouldn’t want to discuss at every single tour stop they send me on doesn’t go in. I don’t really write explicitly about politics. All my s--t is political because I’m a Black woman married to a woman in America, so it’s kind of suffused with politics whether I want it to be or not. People know how I feel or where I stand, but I don’t get deep on politics because I don’t have any political education. I could say I think we need welfare to help take care of people who are struggling because that is what I believe, but I cannot elaborate on it, or tell you where it would come from, or what the tax rates are, you know what I mean? I never get in over my head because I have to be able to defend myself or defend my work when someone brings it up to me. If I can’t, I don’t do that.

VMS: You don’t owe your audience everything.

SI: There’s no way to have personal friendships or relationships with people if they cannot trust you’re not recording everything they say to use. Sometimes I’ve just got to be a friend to my friends and not a chronicler of whatever dumb s--t we’re doing. I do sometimes feel guilty about not telling people things, which is crazy. I can do anything I want, but I also feel like a publicly owned person. I’ll have to unpack that with a doctor. It’s okay for me to have secrets.

VMS: How did you get into TV writing?

SI: First, Abbi Jacobson of A League of Their Own reached out to me a billion years ago about adapting my book Meaty for television. Honestly, I’ll try anything, right? It seemed like a good opportunity. I don’t have any ambition; I mostly just don’t want to suffer. So, I’m like, if I do this thing and we make it, I can make what per episode? Great! I didn’t know it was going to be six or seven years of long, drawn-out Hollywood BS. We started that process and took the meetings, sold it, and blah, blah, blah, but that’s not really TV writing because I never got to see any of that made.

VMS: I love that you shared that experience in Quietly Hostile because it was really cool to hear about a successful writer who struggled with a project.

SI: Selfishly — and this is the drawback of sharing things — I had spent so many years on the script, revising and writing new scripts, writing 700 versions of the same 22 minutes of television. I do not like to work that hard and waste it. If I write a long thing for somewhere and they don’t want it, it’s going in a book. If I wrote something for my newsletter and never sent it, I have to figure out a way to make money off it. I had this script, and I was like, this is getting me paid, somehow, someway. That coupled with “Hey, Sam, I checked Comedy Central, and I don’t see your show on the docket!” [and]

“Hey, Sam, when can I watch your show?” I wanted to shut those people up. I don’t think I’m mad about this — it just is … something — but no one tells you it can take seven unpaid years of your life to still end up with no show. Someone could use that lesson. Someone can use the demystifying of the Hollywood development process from someone who lived it. I have no reason to sugarcoat any of it, so I was like, this is going in the book.

My first official TV writing job — I’m going to go ahead and thank Lindy West, who gave me my first Hollywood writing job. She got to bring one person of her choice into the room [on Shrill], and it was me, and it was an incredible experience. I was a staff writer on that show. My first time in a writers’ room was incredible. Trying to make my own show, which was a process I started in the Paleolithic age, obviously did not pan out for me. But getting to work on Shrill then kicked down a lot of doors for me, and it’s been cool. I’m so grateful for that opportunity.

VMS: What do you know about business now that you wish you could have told yourself when you first started?

SI: Honestly, books have been a dream. I have literally no complaints. I have the best editors. With books, I would say it’s much more of a collaborative effort. It’s not just me and my editor. It’s me, my editor, my editor’s assistant, the copywriter, the sensitivity reader, the marketing people. I don’t choose my own titles, I don’t pick what order the essays go in, and I don’t decide what gets thrown out. It is amazing to be able to trust that it’s going to be good. I don’t have to keep a gorilla grip on things. Joan [Wong], who designs my covers, these are as much her books as they are my books. I didn’t realize how supported your book will be by other people.

With TV, the thing I wish I had known was it is 99 percent rejection. And I’m realistic, right? I never quit my job because I believe in getting paid. I never threw away any opportunities because I believed my show was going to blow up. So, I feel almost sensible in hindsight, but I wish I had known that they’re okay wasting your time or optioning your show because they have another show that’s like it, and they don’t want you to make that at another network.

But you know what I really wish I had known? Just because people seem to like you, that doesn’t guarantee that they like you, and it definitely doesn’t guarantee that they want to buy what you’re selling. As I said in the piece, I have never had a bad Hollywood meeting. Everyone was so great! I thought I was going to marry every single person behind every desk. Years and years ago, I figured that if people didn’t want something, they’d be honest and tell you, and not tell you you’re a genius. I wish someone had said, “FYI, not real. They’re being nice.” That would’ve saved me not even disappointment, but confusion. I guess the big lesson is, it’s really easy to think it’s you. It’s not. It’s what the market wants; it’s what people want. If gross-out comedy isn’t selling right now, stuff they already have on the docket — there are so many factors that have nothing to do with my being terrible. Because I just assumed that I’m f--king horrible.

Vivian Manning-Schaffel is a multifaceted storyteller whose work has been featured in The Cut, NBC News Better, Time Out New York, Medium, and The Week. Follow her on Twitter @soapboxdirty.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY