When Breonna Taylor went to bed on March 12, 2020, the last thing she expected would be to wake up to a war zone in her bedroom. Yet, that’s exactly what happened. And that’s how this promising 26-year-old woman was taken from this world.

What would follow in the months — and, now, year since — are global protests as Black, Latinx and Indigenous women all over the world identified with Breonna and were reminded of just how easy it would be for them to be gunned down in their own homes by our government under the guise of the “war on drugs.” What Breonna’s death shows us is that the so-called “war on drugs'' is really a war on low-income communities and people of color, with an especially damaging impact on Black, Latinx, and Indigenous women.

By no fault of her own, Breonna was targeted as part of an investigation related to her ex-boyfriend's alleged drug activities, and that was enough for the Louisville Police Department to be granted a no-knock warrant to search her home in the middle of the night.

Breonna wasn’t the first and, sadly, she most likely won’t be the last. No-knock warrants, like the one used that led to Breonna’s death, are used in far too many parts of the country (only three states have banned the practice) — and have resulted in the deaths of a number of Black women and girls before Breonna, including Tarika Wilson, 92-year-old Kathryn Johnston, Alberta Spruill and 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones.

But it’s important to remember these devastating events didn’t just happen randomly. And they aren’t just the result of “a few bad apples.”

They are the result of intentional policy choices.

Breonna Taylor’s death can be traced back to two defining events in the early 1970’s: Nixon’s declaration of the “war on drugs” and the escalated use of Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) teams. Back then, the federal government began incentivizing local police departments, such as the Louisville Metro Police Department, to increase drug arrests in order to access earmarked federal funding to fight this manufactured “war,” and to acquire free military equipment through the 1033 program. These programs incentivize increased drug arrests — by directly tieing the amount of federal funding and extent of military weapons transfers they were eligible for to the amount of drug law enforcement they were engaging in — while equipping local police departments with military-grade equipment and additional funding, often spent on military-style training, to essentially operate as if they were soldiers at war. Those targeted as the “enemy” were often Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities even though they did not use or sell drugs at higher rates than white communities.

Decades later, in 2002, the use of no-knock search warrants was deemed constitutional by the federal courts in the name of the drug war to supposedly prevent the disposal of evidence, dangerously eroding our 4th amendment rights and supporting racially-disparate enforcement tactics. Of the no-knock warrants granted to the Louisville Police Department between 2018-2020, 82 percent of the targets were Black and 68 percent were in predominantly Black neighborhoods in the western part of the city. And Louisville isn’t an anomaly. Research shows that 61 percent of SWAT raids target Black and Latinx people nationally — despite the fact that people of all races consume and sell drugs at similar rates. In the majority of cases, no drugs are even found.

Like Breonna Taylor, thousands of women of color are targeted by the drug war every year. They are strip searched and cavity searched at airports, schools, and on the streets, and they face criminalization and police violence as members of households where other people are — or are perceived to be — involved in the drug trade.

Police also target women who use or sell drugs in an attempt to get them to “flip” on drug sellers or suppliers. Like Breonna Taylor, many of these women are not involved in the drug trade or, in other cases, are minimally or unknowingly involved. Because of mandatory minimums, thousands of women have been given long drug-related prison sentences, and over the past four decades, the number of women in state and federal prisons has grown 800 percent due to practices like this. And as Breonna Taylor’s case so tragically illustrates, far too many have lost their lives at the hands of police.

Even now, attempts — such as the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act that was recently passed by the House — are heralded as “sweeping reforms,” yet do little more than continue to “sweep” these travesties under the rug. In fact, while the bill places restrictions on programs that facilitate the transfer of military equipment to local police departments, it does not outright put an end to such programs. While the bill bans no-knock warrants, it doesn’t outright ban quick-knock warrants — which allows law enforcement officers to knock and immediately enter a home without first getting a response from the occupant; these kinds of warrants can be just as deadly as no-knock warrants, especially if occurring during pre-dawn raids such as the one that killed Taylor and have become much more common in drug enforcement.

If you — like me — do not feel safe in your own bed, you are not alone. Millions of our Black, Latinx, and Indigenous sisters and daughters have had the same visceral reaction to Breonna Taylor’s tragic death. It’s time we take back the ability to get a good night’s sleep.

We deserve better. We deserve a world where we can thrive and, frankly, just be able to live another day — regardless of whether or not drugs are in the picture. For far too long, drug involvement, whether perceived or real, has provided a convenient cover for violent and often fatal law enforcement interactions to occur, and that must end.

Ending the failed war on drugs will not end racism and violence against Black, Latinx and Indigenous women, but it will disrupt a system that chips away daily at the very core of our humanity. We don’t need symbolic gestures, we need to strategize, organize, and build campaigns to ensure tragedies like Breonna Taylor’s death never happen again.

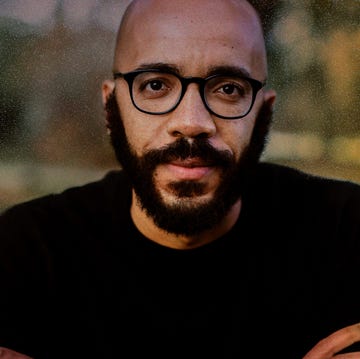

Kassandra Frederique is the executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance, a national nonprofit that works to end the war on drugs and build alternatives grounded in science, compassion, health, and human rights. During her time at DPA, Frederique has built and led innovative campaigns around policing, the overdose crisis, and marijuana legalization—each with a consistent racial justice focus. Follow her on Twitter @Kassandra_Fred.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY