Celebrating the contributions of Black people in America is an important part of our country's story. But too often reflections on Black History Month focus on a few iconic figures, and not the myriad of unsung heroes who've influenced our lives. This year, we're highlighting some of the women making Black History NOW, from a chief economist and a woman fighting to expand voting rights, to a trailblazing Attorney General working to protect the rights of others, this group of groundbreaking women are making the world better today.

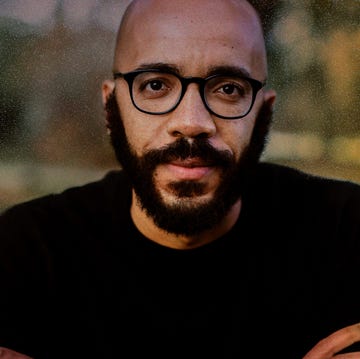

Mary Annaïse Heglar is one of the most influential women in the climate movement, but she’s not a scientist. As the co-host of "Hot Take" and the 2020 inaugural writer in residence at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, Mary doesn’t spend her time analyzing data or poring over policy proposals. Instead, she tells stories.

“I started looking at the story of the climate crisis — realizing it was incomplete and it was incomplete at the beginning, the end, and the middle. The most vulnerable people — who look like me — were missing,” she says. “To me, that felt like an injustice. So I started listening. I knew that there were things that needed to be said and I kept listening for them, and kept listening to them. But I never heard people in power say them. So I started saying them myself.”

While the hard sciences and government action are invaluable in the existential fight for our planet, she has proven to tens of thousands of people that storytelling — which serves as both salve and sword — is a critical tool in saving the world, even if it’s not easy.

“To write about this horrifying thing, I have to be willing to go really far into myself,” she says. “It's like performing open-heart surgery on yourself every single time you sit down to write.”

Along with co-host Amy Westervelt, “Hot Take,” which they describe as a “holistic, irreverent, no-bullshit look at the climate crisis” puts race and gender politics at the forefront. Online, she also spends time “cyberbullying fossil fuel companies” and talking about her love for bats, flying mammals that she’s obsessed with because they’re “cute and unfairly maligned.”

But at her core, the Oberlin College alum is a climate essayist, and her work has been a quaking force in the climate world, forcing people to reckon with the gruesome relationship between our dying planet and the cruelty inflicted on Black, indigenous, and other people of color.

Black and indigenous people, the colonized and the oppressed, have long suffered the worst impacts of the climate crisis — disease, polluted neighborhoods, the destruction of homelands, and death by natural disasters. Because environmental racism negatively affects communities of color, the driving force behind Mary's work is saving Black people. But, she admits, that comes with a lot of handholding and teaching some white people how to put aside their biases to save themselves.

“We’ll all die if nothing changes. So, it’s not like I can wipe my hands and walk away. This is the climate crisis, this is the potential end of life on Earth,” Mary says. “There have definitely been times where I've been like, ‘You know what? F—k it. I'm just gonna work on my own community. But white people hold all the power and I can't leave them with that type of power. So they’ve got to get to work.”

Because of her large social media following, people have continually tried to make her something she is not — a leader of the climate movement, a scientific expert, or a token.

“It is a struggle because people try to make me all sorts of things,” she admits. “There are so many assumptions about what a climate activist is or what a climate advocate is or what a climate expert is. I ain't never claimed to be an expert on this. I just write, and I write for Black people.”

In this, her conviction is reminiscent of one of her literary heroes, James Baldwin, who once said, “I know I can’t drink a truck. And I can’t run a bank… And I can’t lead a movement. But I can f—k up your mind.” It’s Heglar’s refusal to be a token, and her centering of Black people in the fight against environmental racism, that does just that: changes minds.

In her essay, “Climate Change Isn’t the First Existential Threat,” Mary argued that people of color have been in existential danger for years, thanks to America’s penchant for racist violence. Alongside graphic images of lynchings, she invited white environmental activists to imagine a different kind of existential threat — the terrorism of the Jim Crow South.

“Lynching was not some abstract threat or a one-time event. It was omnipresent. It hung in the air like humidity. Or the stench of burning flesh,” she wrote in the essay. After its release, she received much verbal abuse, death threats, and ostracization.

But many white people in the environmental movement did internalize her message — and her essay was a kind of a reckoning that some of them simply could not abide.

“There was way more love than hate. I can't emphasize that enough,” she says. “But the hate was really, really hateful. The day I published it was very rough for me.”

That essay was also a reckoning that drew more Black, indigenous, and other people of color to her work as they continued to assert themselves in the environmental movement. And that, she says, is why she does it.

“Nothing makes me happier than hearing from Black people who say ‘You’ve made me feel like I can speak up in this space and I can be a part of this movement, too,” she says.

For her, the heightened visibility is worth it if she can just get “one Black person to see themselves. To see this planet as belonging to them.”

A daughter of the South — born in Alabama and coming of age in Mississippi — Mary feels that communing with nature is “a very deep form of rebellion.”

“We were taught on penalty of death that being in the South is like always being at the scene of the crime,” she says. “But we also love nature; nature wasn't the thing that harmed us. Like the trees were not things that harmed us. The magnolias, the okra, the deer… all of that is not what harmed us.”

It was, she stresses, white people who “weaponized the Southern landscape” against Black people — by forcing Black folks to work the land to build this country, or by using the land to kill us.

“If you look up pictures of Black people with trees, they're usually hanging from them,” she says. “But no, these white folks don't get to have my planet.”

Although she currently resides in the city, it is the people and the soil of the South that is the pulse of her writing, especially the Black South’s literary tradition of a deep, eternal feeling of the majesty of the land. The authors who shaped her own writing include James Baldwin, of course. But also Margaret Walker, Toni Morrison, and Octavia Butler, to name a few. When I mention that the South — particularly Mississippi — is one of the overlooked meridians of literature, and her face lights up.

“Yes. Mississippi has produced like half the canon of great Southern literature. Southern and Mississippi writers, in particular, are very good at nature personification,” she says. “You can't look at a tree in Mississippi and think you're better than it. You have to see it as a sibling. You can’t look at the Mississippi river and not see that as a living, majestic being.”

“I feel like Mississippi is where the English language goes to be broken down and made whole, into a language that like nowhere else in the world,” she continues. “I’ve been reading a lot of Mississippi literature this winter because I’m homesick.”

Then she laughs, “If my Alabama family reads this, they’re gonna be like, ‘Really?’”

For Mary, the climate movement begins and ends with Black and indigenous people. Not just their oppression, but in their power to rise up. But she won’t be holding anyone’s hand as she writes, and she certainly won’t consent to sanitizing her message about Black people, and our place on this earth, and in the Climate Change movement. “Y’all can handle it, or you can find somebody else to listen to,” she says. “I won’t cower to those criticisms.”

Nylah Burton is a Washington D.C. based writer. Follow her on Twitter @yumcoconutmilk.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY