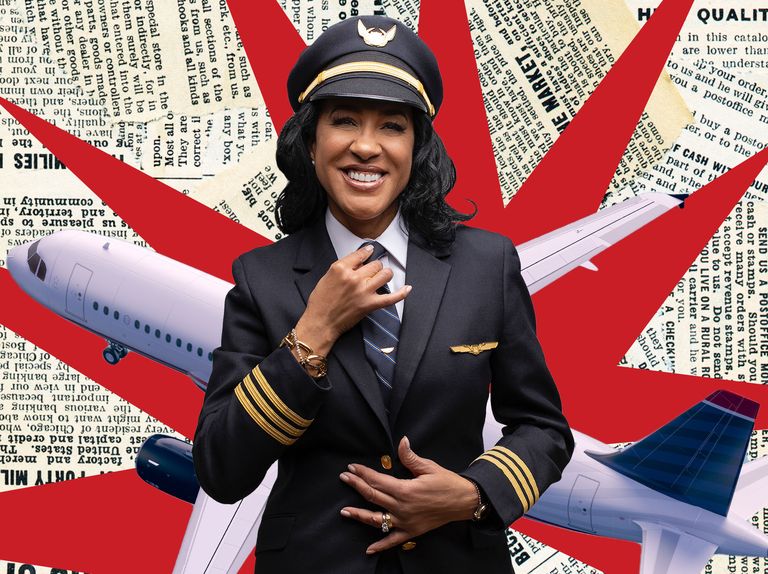

Pilot Carole Hopson flies a Boeing 737 for a living as a United Airlines first officer. But she often gets mistaken for someone else.

“I get confused with a flight attendant, or anybody — cabin crew, even a gate agent — anything but a pilot,” she says.

It happened to her the day before our conversation — twice. As a delightfully cheery person, Hopson was chatting with a stranger in the terminal before boarding a plane, as she does before many flights. But when she crossed the jetway, he asked her if flight attendants get to fly for free.

“Our flight attendants are amazing,” she says. “They know CPR. They know how to get people off the airplane in an emergency. They save lives. So, I never get upset about that. But here’s what I say: ‘I’m not a flight attendant. I’m a pilot.’ It’s just a statement. That’s it.”

Based in Newark, New Jersey, with her husband and two sons, the United Airlines first officer takes it all in stride. “The look on their faces ... I do wish I had a picture,” she laughs. “But to ridicule them, I don’t think they’d get it. And they’d walk away saying, ‘What a jerk.’ But instead, I think they walk away with this sense of wonder like, ‘Shoot … How did she … What in the world?’ A thousand questions that they almost wish they had asked while they were sitting next to me.”

When she began working at United Airlines as a first officer, she was one of two female pilots out of a class of 40 — and the only Black woman. “It is stunning,” she says, “and it makes you silent. Like, why?”

This is why Hopson is on a mission to diversify the flight deck and make her profession more accessible for underrepresented communities. More specifically, she’s on a mission to help more Black women become pilots.

Hopson says that this lack of representation and exposure is evident in many of the communities she enters — even right at home. “Take right here in Newark,” she says. “The airport is [about] 14 miles from the church that I used to attend. When I would go in there and talk about this, people had never been on airplanes. … They had been in the airport — maybe they cleaned planes or worked the concessions. But they certainly had never, ever thought of this as a career. How is that?”

According to the most recent Federal Aviation Administration statistics, about 720,000 people are employed as professional pilots, but fewer than 9 percent of them are women.

“That’s crazy,” she says. “When I get in the airplane and I look over my shoulder, more than [that percentage] of our passengers are women. Arguably, it’s half.”

African Americans account for even less of the profession at just above 3 percent, according to a 2022 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Advocacy organizations like Sisters of the Skies have gathered that there are fewer than 150 Black female pilots who fly for a living, or less than 1 percent overall, in the United States.

“How do we make history? How do we change the trajectories of women and our families? We shine light on an opportunity that they didn’t even know existed,” she says.

Hopson has wanted to fly a plane since she was a little girl. She used to lie in her nana’s backyard and look up at them, like stars, taking off from the Philadelphia International Airport down the street. Hopson recalls her grandmother Lorene’s wanderlust, which took her all the way to Russia as a Black woman in the 1970s, and how she brought back replicas of Fabergé eggs, nesting dolls, and paperweights.

“She stoked my imagination,” says Hopson, who made up stories about where the planes were going and traveling from, what the passengers were eating, and how the engines worked.

When she boarded a plane headed to Bermuda for a family vacation at 12, she remembers seeing these “beautiful Black pilots” and thinking, “Oh, my God, now that’s something I never thought of,” but they were men. “It just seemed so far away,” she recalls, as distant as putting on a pair of shoes and walking to the moon. “I just couldn’t get my arms around how I would get started.” So, she chose journalism.

After Hopson graduated from the University of Virginia, her first job was working for The Philadelphia Tribune and then as a police reporter for The Bergen Record in New Jersey. She reported on racial profiling in the densely packed state for five years. One day, a detective called to tell her they found the body of a young girl they were searching for.

“The sight of a teenager’s body just changed my life,” she says. “Something happened to me, and it revolved around a level of violence that I don’t think anyone should get used to seeing or being in. … So, I stopped being a reporter.”

She left journalism and started a career in media relations and human resources, first at the National Football League as the player programs coordinator and then as the vice president and director of training and development at Foot Locker. It was during this time that she went on a date with her then-boyfriend, now-husband, Michael, that changed her trajectory forever.

At the end of their date, Michael asked her what she wanted more than anything. Hopson recalls, “I said these words for the first time, getting very emotional: ‘I want to fly a plane.’” Two weeks later, she lifted up her place mat after dinner and saw an envelope with her name on it. It was a gift certificate for flight lessons at Teterboro Airport in New Jersey.

The experience didn’t just inspire her to fly; it made her want to become a pilot. She told Michael she wanted to leave her job to pursue this path, and they created an exit strategy together. They got married and moved closer to training academies, and Hopson took a job as the director of human resources at L’Oréal cosmetics to save up money for flight school and prepare for her transition. In eight months and at the age of 36, she went from being a full-time executive to a full-time flight student.

Getting that certificate changed everything. “It was like a genie uncorked the bottle. It was like toothpaste out of the tube. You can’t put it back in,” she says.

Hopson faced backlash from various people who said that it was too late to start a new career and foolish to leave a comfortable situation. But she was okay with being uncomfortable.

“There’s a sort of hunger that burns in people who were not born comfortable,” she says. “I wasn’t born comfortable. And by choice, I stay there.”

History is made by taking risks, and Hopson was willing to take a few. The quantum leap of faith as a Black woman into the aviation industry taught her that although we’re in the same room as everyone else, we’re not necessarily in the same row — especially when it comes to the cost to get in these rooms.

“What it does, to put someone in a role like this, is to change economics for our community,” she says. “There is power in economics. There is power in making this an opportunity that little girls think of.”

Hopson traded in her executive job making six figures a year to make $17 per hour at first as a flight instructor, but it paid off. “This is a lucrative career,” she says. “We have people at the airline who make $200, $300, $400 an hour,” and who only work between 12 to 18 days a month, giving pilots flexibility, work-life balance, and reproductive freedom.

Once Hopson realized how much of a difference it made in her life both personally and financially, she thought, “Where shall I cast my future? Because I don’t have a whole lot of time. So [with] the time that I have, how can I make every single day, every single flight, every single moment count?”

The aviation industry is currently facing a verified shortage of pilots. “That means that an essential service — the national backbone of our country which is our air transport — will be changed if we don’t get ahead of it,” says Hopson, who developed a personal interest in assembling the next generation to help reverse that.

“Every talk I give, I talk about the difference between a dream and a goal — it’s two words: a date.” By the year 2035, Hopson hopes to have 100 women of color enrolled in flight school through her nonprofit Jet Black Foundation, whose mission is to equip women with access to the education and training they need to earn their pair of wings. She’s calling it the 100 Pairs of Wings Project, and it would almost double the amount of licensed Black female pilots there are now.

At Luke Weathers Jr. Flight Academy in Memphis — named for the Tuskegee Airman who was also the first African American air traffic controller at Memphis International Airport — these 100 women will not only learn the necessary flying chops, but will have invaluable help navigating their certification journey.

Hopson knows firsthand how disorienting starting the process can be when one is unfamiliar with the world of aviation. “I didn’t know anything. It was like they dropped [me] off in Berlin and said, ‘Order your meal’ … but the language was different.”

When Hopson was new to the industry, she had a plethora of questions: Which licenses did she have to get, and what tests did she need to take? What was required to get them, and how should she prepare? From finding what flight schools existed to crafting a flying résumé — which is quite a departure from a traditional résumé — it wasn’t easy to figure out on her own. That’s what she hopes to make easier for the next generation.

More importantly, there are a number of nuances that bar people — especially people of color — from entry, including exposure, access, and financial feasibility. Pilot training costs as much as $100,000 to $150,000 per year at most for-profit flight schools. At Luke Weathers, which was founded by the Organization of Black Aerospace Professionals, flight school is about one-third of the cost at $55,000 to $75,000, thanks to it being a nonprofit that is located in Memphis, where it’s less expensive to fly. The Jet Black Foundation cuts the cost even more, providing two-thirds of the funding for each young woman.

“It is so important to change the economic path of Black women in this country,” she says, adding that the lack of money — and not having the economic freedom to pursue these types of opportunities or to learn through traveling — is one of the biggest barriers to success.

She recalls her own financial path and the three-plus years it took her to save up for training. “I was able to choose to go to flight school because I had the finances to do so,” she says. “It’s darn hard if you haven’t had the opportunities that I had.” To her, it cost time. “Other women, it’ll cost them in time and money. How do we change that?”

Hopson believes that to be it, it helps tremendously to see it. Every treasure is surrounded by dragons, she points out, but asks, “Why do we all have to go out and slay the same ones? Why can’t I go through this and just lead you? Bessie Coleman made a path. My job is to make it smoother.”

There is one day Hopson remembers vividly because it changed the course of her life. At the end of her first aviation convention, a woman named Captain Jenny Beatty — who would go on to be her mentor — presented Hopson with a mug that had a photo of Bessie Coleman on it.

“As I unwrapped it, something happened to me,” she says. “It was like a movie moment. Everything around me slowed down.” The photo on the mug would end up being on the cover of her book 24 years later.

A Pair of Wings, Hopson’s historical-fiction novel inspired by the life of the pioneering aviatrix Coleman, came out on June 11, 2021 — almost 100 years to the day after Coleman became the first Black and Native American woman to earn her pilot’s license.

Hopson — who graduated with a degree in literature from University of Virginia and a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University — says that until that day at the convention, she “didn’t know who Bessie Coleman was.” She asks the question again: “How is that?”

In school, Hopson learned about white pilots such as Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh but never heard the name Bessie Coleman until she was an adult. “When she died, she was 34 years old. When I learned who she was, I was 34 years old,” she says. “Bessie Coleman was peerless. Amelia Earhart was two years after her.”

Throughout our three hours together, Hopson talks passionately about Coleman’s story. She tells me Coleman was the daughter of an enslaved person who grew up working as a maid alongside her mother and that she was the first in her family to attend college — all while casting the characters of Coleman’s life along the way (Will Smith would be good in the role of the Black self-made banker who helped her travel to get her license).

Hopson was, and is, deeply inspired by Coleman’s life. When Coleman was 26, she decided to spend three years learning French and raising the funds to get her wings. Then, at 29, she traveled to France so she could learn how to fly — as no one in the U.S. would give a Black woman flight lessons.

While researching for the book, which was dubbed an Oprah Daily pick a month after its release, Hopson traveled to every destination Coleman flew with the exception of Berlin. She wanted to experience the tremendous things Coleman did, including learning her famous flight stunts that earned her the nicknames “Brave Bessie” and “Daredevil” through biplane lessons and even walking nine miles in the same style of leather shoes Coleman wore (the same two hours and 15 minutes Coleman walked to her flight lessons in France).

“In so many ways, we have to reach back 100 years to look forward into the next 100 years,” Hopson says. As Coleman did for her one century ago, Hopson wants to continue blazing a path for those coming behind her. Coleman carved out a path where there wasn’t one, and Hopson hopes to make that path even wider.

The pilot and author visits high schools to talk to students from underrepresented communities about flying as a viable career path. She also actively raises money on her own to reduce and remove the financial burden of flight training. All of her speaking fees go straight to the Jet Black Foundation, as do 20 percent of the proceeds from her book. She plans to raise a total of 7 million dollars through the Jet Black Foundation to help pay the way for each of the 100 young women.

At the thought of making history, particularly Black history, Hopson gets emotional. “I don’t think I ever set out to create any history. I did not,” she says. “I set out to fix something that’s broken. I set out to right what I see as a wrong. It’s wrong that little Black girls don’t see themselves in positions that can change their lives, that can change their finances.”

The 100 Pairs of Wings Project aims to launch its first class by January 2023. “We want 10 [classes] every year,” she says. “Every time I say it, I get a little shiver, and I get a little chill because it is so thrilling.” And every time she flies, it’s more of the same thrill and playful joy she so effortlessly exudes, the same knowing that it’s where she’s meant to be.

Mia Brabham is a staff writer at Shondaland. Follow her on Twitter @hotmessmia.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY