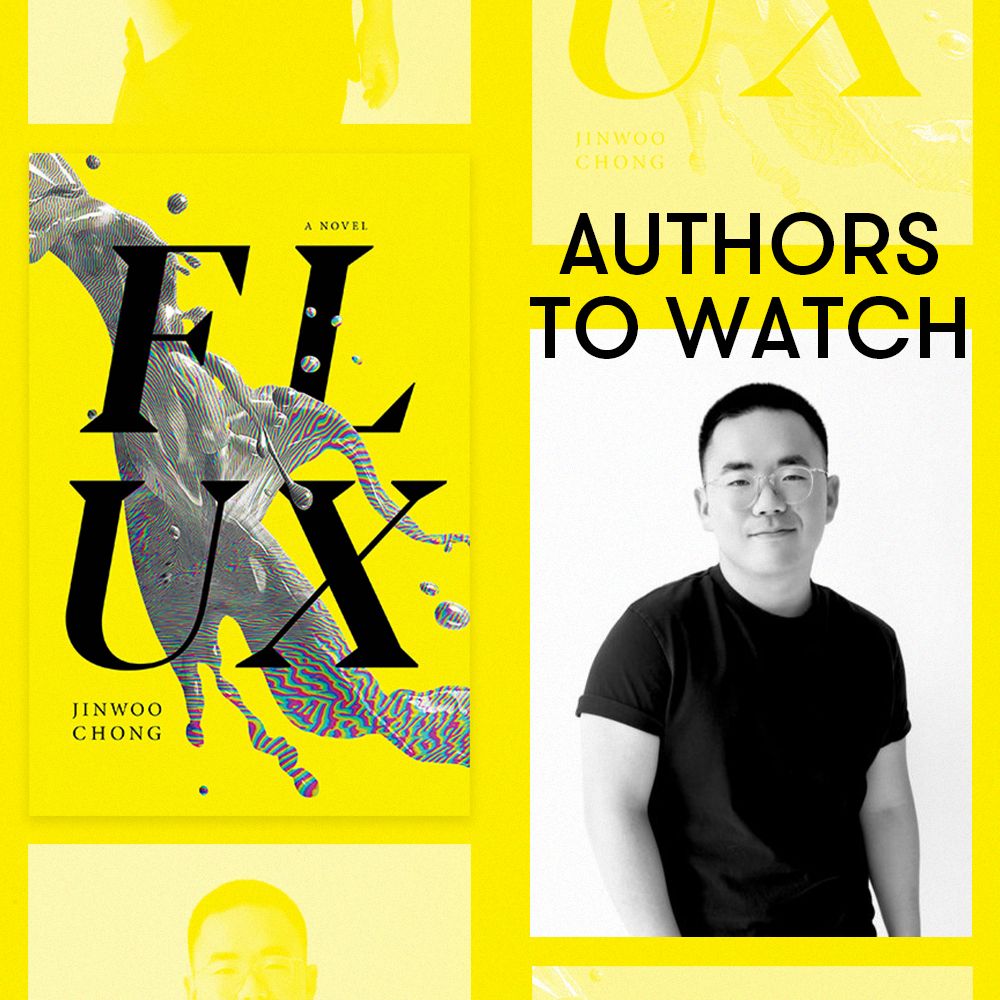

Writing a book is no small feat, especially as a new author. The late nights, the revisions, the self-doubt — all for the glory of seeing your book in the hands of enthusiastic readers. With that in mind, each month Shondaland’s Authors to Watch series highlights an exciting debut writer whose work we want to recognize. Let’s welcome these new voices on the literary horizon together.

There are three characters at the center of Jinwoo Chong’s cinematic debut novel, Flux, all dealing with different degrees of loss. Bo, age 8, loses his mother; Brandon, age 28, loses his job at a magazine, only to be offered a mysterious new position at a tech startup; and Blue, age 48, has lost his voice but gets a temporary voice implant in order to be part of a documentary about a failed company called Flux.

The book alternates through Bo’s, Brandon’s, and Blue’s perspectives until these three threads ultimately converge, revealing secrets and layers of a newfound technology that has life-altering consequences. Interwoven in the story is Brandon’s obsession with and analysis of an iconic character from a fictional ’80s detective show called Raider, who was played by an actor embroiled in a MeToo scandal. Flux is aptly titled, and Chong’s ability to tell a nuanced, intricate, and page-turning story shines in this immersive novel.

Shondaland spoke with Chong over Zoom about scams and scammers, identifying with pop culture, masculinity and queerness, and the unexpected joy of architecture.

SARAH NEILSON: Was there any seed or specific inspiration behind this story?

JINWOO CHONG: The seed was Bad Blood by John Carreyrou. I read it right when it came out in 2018, and I was spellbound. The idea of the life cycle of a lie and the weight that it takes on, and all the hot air that gets blown into it by hype and exacerbated by the media, and then the spectacular implosion of it — that was really interesting for me to track on a plot level. I was fascinated by Elizabeth Holmes because the sense that I got from her was that she sincerely believed in her own mission. She actually thought she was doing good work and making it happen. I wanted to convey a fictional sort of retelling of that. I was working on this novel while in my MFA at Columbia, where in a workshop environment I feel like the usual push is toward the literary and to be more highbrow about things. Within that sort of incubation environment, I started adding more elements of pop culture and sociology and all of the different kinds of questions that arise about celebrity and our consumption of celebrity. Along with that was the ’80s television show that is a through line through this novel. It felt natural by the end to have some timeline of celebrity that develops parallel to each of the characters. So, there’s a lot of different jumping-off points that began with Theranos and has ended now in this complicated story, but [it’s] the story that I wanted most to tell.

SN: I love how you approach writing about pop culture, especially that aspect of lodging a part of your identity in something outside of yourself. It’s really interesting how you render the betrayal and the loss of that piece of identity, piece of self, when something breaks it. Brandon speaks to the character in the second person as separate from the actor who played him. What felt important to you to explore about trying to sever the bad part while keeping the good part intact as a way of self-preservation, and about pop culture and parasocial relationships?

JC: I think that’s totally right, that Brandon’s reflex is to separate the two in reaction to pain and loss that he feels at having been severed from this character that is such an integral part of his life. And I think that that happens with a lot of fans of problematic people. I feel that way about Call Me by Your Name because the movie made me very emotional and is a focal point of my own embrace of who I was back when I was a young adult watching this movie for the first time. And now I feel that in some ways it’s not right to watch it anymore because I can’t look at Armie Hammer’s face without associating him with all of the real-world parts of it. So, I feel like the journey that Brandon takes with this is something that happens to a lot of people who are fans of something that just turns sour or that becomes poisoned or infected by things that wouldn’t matter if we’re really separating art from the artists. But that’s impossible to do, and it’s ultimately just this messy thing that is inevitable, but everyone has a different way of coping with it.

SN: How does the book grapple with trauma with these three characters?

JC: The fun part was to deal with three characters — Bo, Brandon, and Blue — who kind of negotiate their own grief in different ways, even though [there’s a twist to it]. That was a lot of fun to try and parse through, especially because Bo deals with his grief by sort of begging people to acknowledge it. And in a very childlike way, reaching out for someone else to do this lifting for him or to absorb some of his pain for him. Brandon, on the other hand, is completely pushed away from everybody and labors to make that happen in every interpersonal relationship in his life, including with his family. And Blue has reached a point in his life where all that he’s fixated on now is this trauma of decades ago. It consumes him so much that he doesn’t really live in the present anymore.

SN: How did you approach playing with and exploring time and the nature of time — nonlinear time, cyclical time, and looping time — in this story?

JC: With Tylenol, I guess, because it gave me headaches constantly. This was a very complicated thing to try and tackle, especially because what I wanted to be able to say about this book is that the lives of characters interact with and touch each other as Brandon’s grip on reality kind of disintegrates and his use of Flux turns into abuse of that same technology. I got really lucky with how it all came together. Even in writing it, it was surprising the connections I was able to make. It was a very improvisational process when I was outlining this novel. It kind of spoke to what I was trying to say about time because we’re thinking creatures and we kind of exist in multiple planes at all times — it’s tough to follow one track at any given moment. A thought can speed you in a separate direction into something else, and suddenly you’re 10 years old again, or you’re imagining a future in which you’re 55 years old. At least, that’s the experience I have when I become introspective and think about the course of my life. Putting it to paper was a difficult process, but it was really fulfilling to do because I could see a lot of myself in how Brandon views the world and how each of the other characters view themselves.

SN: Circling back to the idea of the scam that you said was your inspiration for the book — it’s not just the one scam of this tech company but also the scam of capitalism, the scam of a silver bullet like a lifetime battery existing, and the scam of an idol or a hero. What felt important for you to explore about the idea of a scam?

JC: I feel alarmed and concerned and nervous about the way that people are so quick in their thinking and their conclusions about things, like even now we’re still fighting off the idea that the election was stolen, just because one guy said something, and then it gets swirled around in a social media vortex. People are so quick to align themselves wholly around something with very little to back it up or without doing any kind of introspection themselves about what it is. That feels scary because I do it too. I think I was also playing into the idea that the scam story is really in vogue right now, and every story has this center to it that is all about people receiving just a hint that their lives could change in a miraculous way. And they put everything into it without thinking, and then more often than not, it just collapses because there was no standing with it to begin with. We see that time and again now with people like Anna Delvey and George Santos. But the scary part is no one seems to care. After the scam implodes, people say, “Well, that was iconic.”

SN: Speaking of writing from a place of concern, anybody who writes now is writing in the face of climate change and the slowpocalypse, where a lot of things seem like they’re collapsing, and there’s this sense of doom. How does climate change and late-stage capitalism inform your thinking and writing?

JC: I think about the novel Severance by Ling Ma a lot when I think of this question, and in her collection Bliss Montage as well. A lot of her characters deal with a changed world or an ending world with utter apathy — the dissolution of everything they know. It doesn’t register to a lot of her characters, and they kind of trudge on. I feel like that’s something that everybody from ages 18 to 40 has been conditioned to do now with decades of one side screaming, “We’re headed for disaster,” and the other side’s saying, “No, we’re not. What are you talking about?” I think the push and pull of that creates a lot of weariness and a lot of inability to compute after a while. I recognize that in myself even, and in the book, when the blackouts keep happening, they barely talk about it. I wanted to capture what that feels like and to maybe capture the kind of revulsion that someone might feel in themselves seeing that happen. Because I feel repulsed by recognizing that in myself and how I react to the world as well. It’s just a lot of self-hate and a lot of depression and a lot of nihilism that keeps us all healthy.

SN: In what ways is this a story of family and heritage? And what felt important for you to dig into about that line of the story?

JC: It seems to be the heart of the book, which is Brandon’s inability to connect with any part of himself. I think the effect that that has on people with that same background is not that they belong everywhere, but they belong nowhere. I feel that as an Asian American person, as a child of immigrants — both of my parents immigrated here at pretty young ages, and as a result, I have trouble relating to being American but also trouble relating to being Korean. I think that has been done in books a lot and way better than I could ever do it. What I wanted to try to do was make it a more literal interpretation, which is probably why I made Brandon half white. And the opportunity to show the ambiguity of his character physically on his face and for people to not know what he was or whether he understands English or Korean ... I wanted it to be a callback to books that I treasure like Invisible Man and The Sympathizer, both of which are narrated by characters who are just unknown, faceless, nameless, and occupy this liminal space. I was really inspired by that, and I wanted to show that literally in Brandon’s character just when you look at him.

SN: Speaking of aspects of identity, can you talk about the masculinity — its cultural limitations, its possibilities — that you explore in the book or that you thought about while you were writing?

JC: There is an interesting evolution now of masculinity that has arisen thanks to social media and people like Andrew Tate, and to a less extreme extent just like male influencers who care a lot about fashion. Also, the fact that Drake has, like, a $100,000 mattress that’s made of fur, you know — these are not things that men in the ’50s ascribed to masculinity but are now engulfed in. And part of the breeding ground for that kind of identity appears to be tech and Silicon Valley. I think it intersects with queerness as well. And the fact that Brandon, aside from having a lot of ambiguity over his racial identity, he also has some over his sexual identity. And to see him struggle with that and to not understand and feel pressured to adhere to a lot of antiquated notions of it, that felt like something very relatable to a lot of queer people — queer men, cis men, and also trans men — who kind of have to define their own place in that conversation.

SN: Is there a work of art or culture that you identify strongly with?

JC: I feel very inspired by architecture. It was very fun to kind of design in my mind the Flux headquarters, which is called F1. And for it to be an amalgamation of what I know about the Apple spaceship and the Amazon spheres, but also have it be kind of edgy, like a Williamsburg warehouse, and have all of that nonsense tied up in it. And then also have it also be like Kim Kardashian’s house. I’m really inspired by it because interior design and architecture is really just your personal preference. That was a lot of fun to think through, and I looked through a lot of modernist American architecture as inspiration for a lot of the different places that you see there. It was an unexpected thing that I found myself getting sucked into every time I started researching for this novel. It turned into a very happy surprise because I like architecture, and I like looking at it and studying it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sarah Neilson is a freelance culture writer and interviewer whose work regularly appears in The Seattle Times, Them, and Shondaland, among other outlets. They are an alum of the Tin House craft intensive, and their memoir writing has been published in Catapult and Ligeia.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY