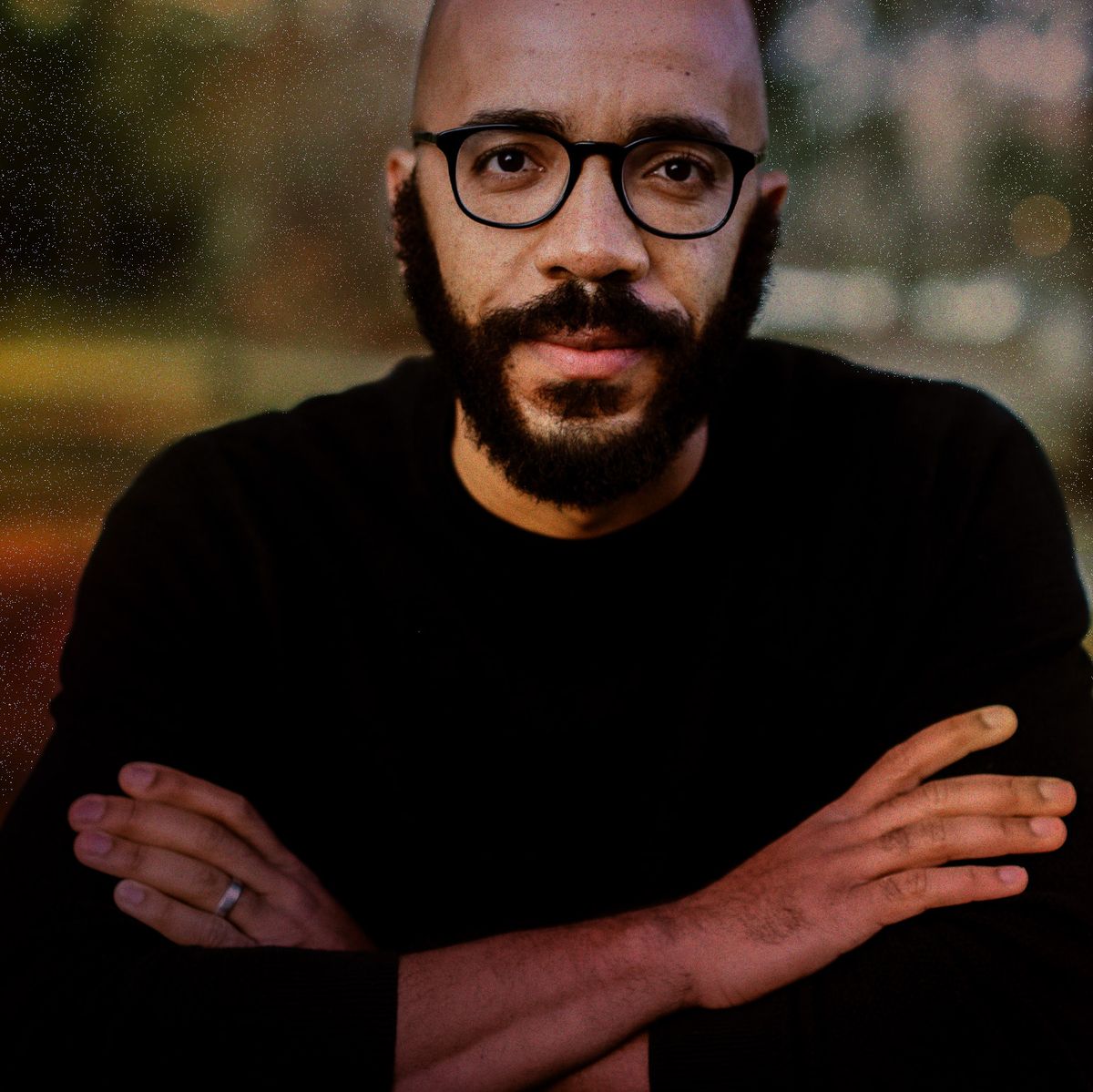

Author, poet, Ph.D., and The Atlantic staff writer Clint Smith has spent years studying the darkest episodes of history to better understand how we collectively atone for a violent and difficult past. The author of How the Word Is Passed has spent years digging deep into the collective mythology and the violent facts of slavery and racism. This week, he published a story in The Atlantic entitled “Monuments to the Unthinkable,” a piece that focuses on how people, communities, and nations account for the unimaginable crimes of the past. His piece expands on the work in his book, taking a closer look at what Americans might be able to learn about how best to atone for our history of slavery and endemic racism that continues to plague this country. His work looks to Germany’s efforts to memorialize the horrific crimes of the Holocaust as a possible blueprint for how the U.S. can publicly remember and atone for its own violent past.

“America has struggled in terms of public memory,” Smith tells me during a recent interview. “Part of what my book was attempting to do was to say, how do the different historical sites across this country — the museums, and monuments, the memorials, the plantations, the prison, the cemeteries — how do they account for and reckon with, or fail to reckon with, their relationship to the history of slavery? The more I went around talking about the book, the more Germany became invoked.”

Smith had never been to Germany prior to his reporting for his Atlantic story, so to better understand just how the German people and government incorporate remembrances of the atrocities of the Holocaust, and the systemic murder of more than 6 million Jews and millions of other people over a period of 12 years, into their daily lives, Smith traveled there. During his time in Germany, he visited government landmarks, concentration camps, museums, and the homes of those murdered by the Nazis. He spoke to everyone from Holocaust survivors to museum directors, authors, activists, and artists to better understand how Germany’s atonement for the Holocaust stands in stark contrast to the way that Americans acknowledge and grapple with our history of slavery and racism.

“We know that symbols and names and iconography aren’t just symbols. They’re reflective of the stories that people tell,” Smith said. “And those stories shape the narratives, and those narratives shape public policy, and public policy shapes the material conditions of people’s lives, which isn’t to say that you just take down a 60-foot-tall statue of Robert E. Lee and suddenly erase the racial wealth gap. But it does help us recognize the sort of ecosystem of ideas and stories and narratives that help ground us in a firmer and deeper understanding of American history and of the ways that certain communities have been disproportionately and intentionally harmed throughout American history.”

Understanding the Role That Racism and Hate Play in Modern America

Racism and hate are ingrained in American culture, industry, and infrastructure. The 2020 murder of George Floyd, the rising tide of hate and antisemitism in public culture, the hateful messages from conservative politicians and the Republican Party, and continuing racial violence are all examples of how racism and hatred are ingrained in American consciousness and culture. Denying these facts is dangerous and false, and it perpetuates hateful prejudices, policies, and culture. But as Smith points out, many of these hateful, racist, and patently false beliefs stem from stories that have been passed down for generations that are not based on any concrete facts.

“For so many people, history is not about primary-source documents or empirical evidence,” Smith says. “It’s a story that they’re told. It’s an heirloom that’s passed down across generations. It’s something where loyalty takes precedence over truth.”

During his research for his book, Smith visited a Confederate cemetery in Virginia with the Sons of Confederate Veterans during their Memorial Day celebration. “The stories that they are telling one another and that they’re perpetuating and that they’re celebrating, those are not stories that are grounded in empirical evidence; those are stories that are grounded in primary sources. They’re the stories that were told to them by their parents and their grandparents, by their community. But that also means that those are stories that are inextricably linked to people and to community and to love and to family. And so, when people are asked to accept a different set of stories, it can become difficult for them because if you tell somebody that the story his granddad was telling him is a lie and it’s false, then his whole entire childhood is not true. It threatens to crumble and disintegrate the foundation upon which his relationship with that person is built,” he says. “It is a threat to their very sense of self.”

Smith continues, “You look around the country, and you look around our society, and you understand that the reason one community looks one way, and another community looks another way is not because of the people in those communities. I think it’s important for any person in this country to be disabused of the idea that the country looks the way that it does because of any sort of natural cultural or social outcome. The landscape of inequality that exists in our country has been created by decisions that people have made that have extracted resources from certain communities and given them to others. It’s so important to ensure that we all understand why our country looks the way that it does.”

What Germany Can Teach the U.S. About Atonement and National Memory

Understanding the real, gruesome facts about why our country looks the way it does is a vital first step, but Smith argues that the U.S. needs to go beyond taking down Confederate statues and renaming streets. While his piece in The Atlantic focuses on questions about what the public memory and atonement might look like should the U.S. create memorials about slavery and racism — like artist Gunter Demnig’s Stolpersteine, or stumbling stones, that mark the homes of Jews murdered by the Nazis, or massive memorials like the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe — Smith says that atonement and national memory of slavery and racism must begin with individual people.

“What I learned in Germany, and I think what you see here, is that rarely do these initiatives begin from the government,” Smith says, “It is ordinary people who see a gap that exists and who recognize that the way that we remember something is inadequate, or is distorted, or is flawed. The stumbling stones weren’t started by the German government, saying we’re going to create the stumbling stones. It was started by one man, one artist who started putting these stones in the ground in his hometown of Cologne.”

Those stumbling stones are everywhere across Berlin, where people walk past them every single day on their way to work, to the store, or when they return home. The national memory of the murder of millions of people under the Nazi regime is integrated into the fabric of everyday life. It’s an unavoidable fact that is continually visible across Germany.

“Part of the lesson is that you don’t have to wait for anybody. Right? Part of the lesson is that you can begin things in your own community, in your own city, in your own county,” Smith says. “There’s an opportunity to create initiatives that can really transform your own community’s understanding of itself.”

What Happens if the U.S. Doesn’t Atone for Its Past?

Winston Churchill famously paraphrased Spanish philosopher George Santayana in 1948, saying, “Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.” It goes without saying that if the U.S. and its citizens refuse to acknowledge the violent history and current impact of slavery, racism, and hatred on our nation, we cannot learn from it, prevent it from happening in the future, or heal from it.

As the U.S. continues to grapple with everything from hate and systemic racism to antisemitism, racial violence, and the banning of books about the darkest points in our collective history, it’s high time that we all work to understand the violent bedrock that this country was built on. The questions that Smith raises in his piece offer a glimpse of hope and a possible blueprint for how the United States might appropriately and comprehensively begin to grapple with its violent and repressive past. While Smith doesn’t have the answer to this tremendous question, he offers up probing insight and hope for the future of America’s atonement.

“I think if you look across history, you see people with quite extreme views change over time for a variety of reasons. There are all sorts of different catalysts to shifts and people’s ideas and dispositions and sensibilities. I don’t subscribe to the belief that different groups of people can never recognize their interconnectedness to this history,” Smith says. “My hope with this article, my hope with my book, my hope with a lot of my work is to reach folks who simply might not have thought about it in these terms. And to maybe open up something inside of them that allows them to ask a new set of questions.”

For more at The Atlantic, visit www.theatlantic.com.

Abigail Bassett is an Emmy-winning journalist, writer and producer who covers wellness, tech, business, cars, travel, art and food. Abigail spent more than 10 years as a senior producer at CNN. She’s currently a freelance writer and yoga teacher in Los Angeles.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY