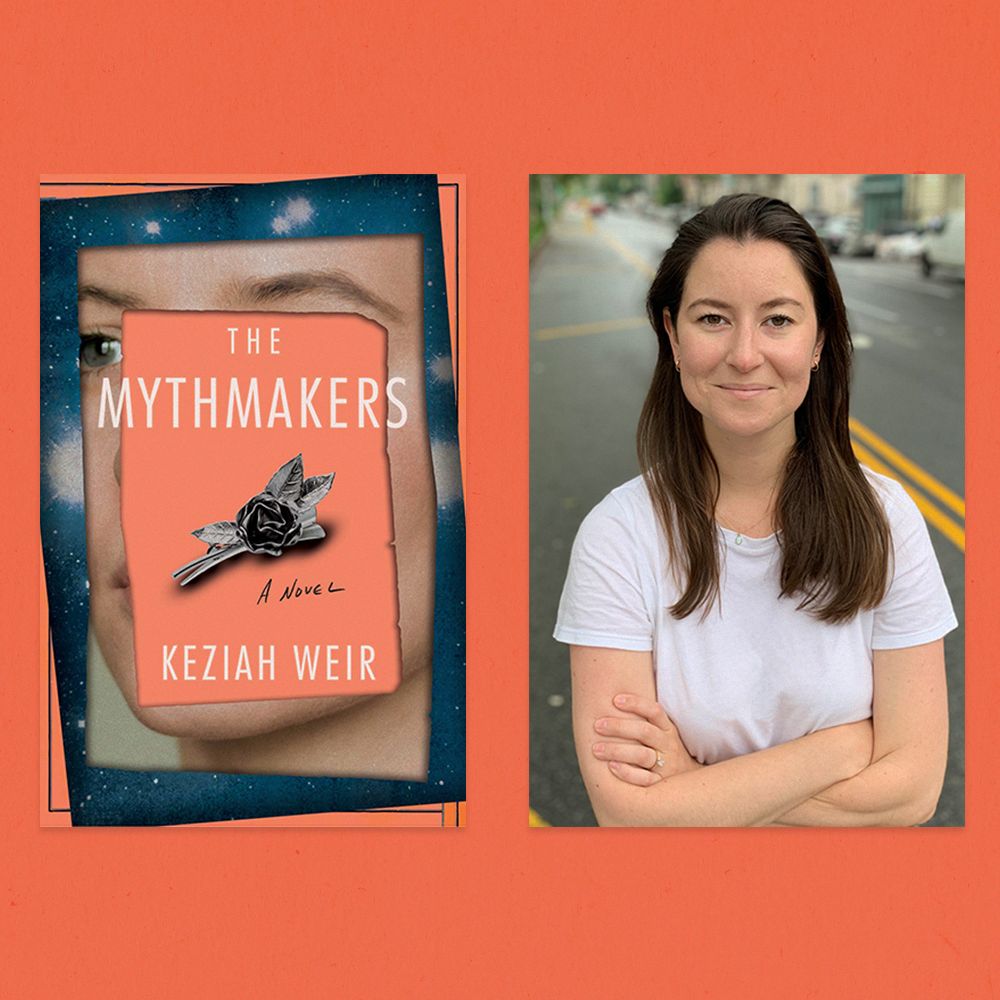

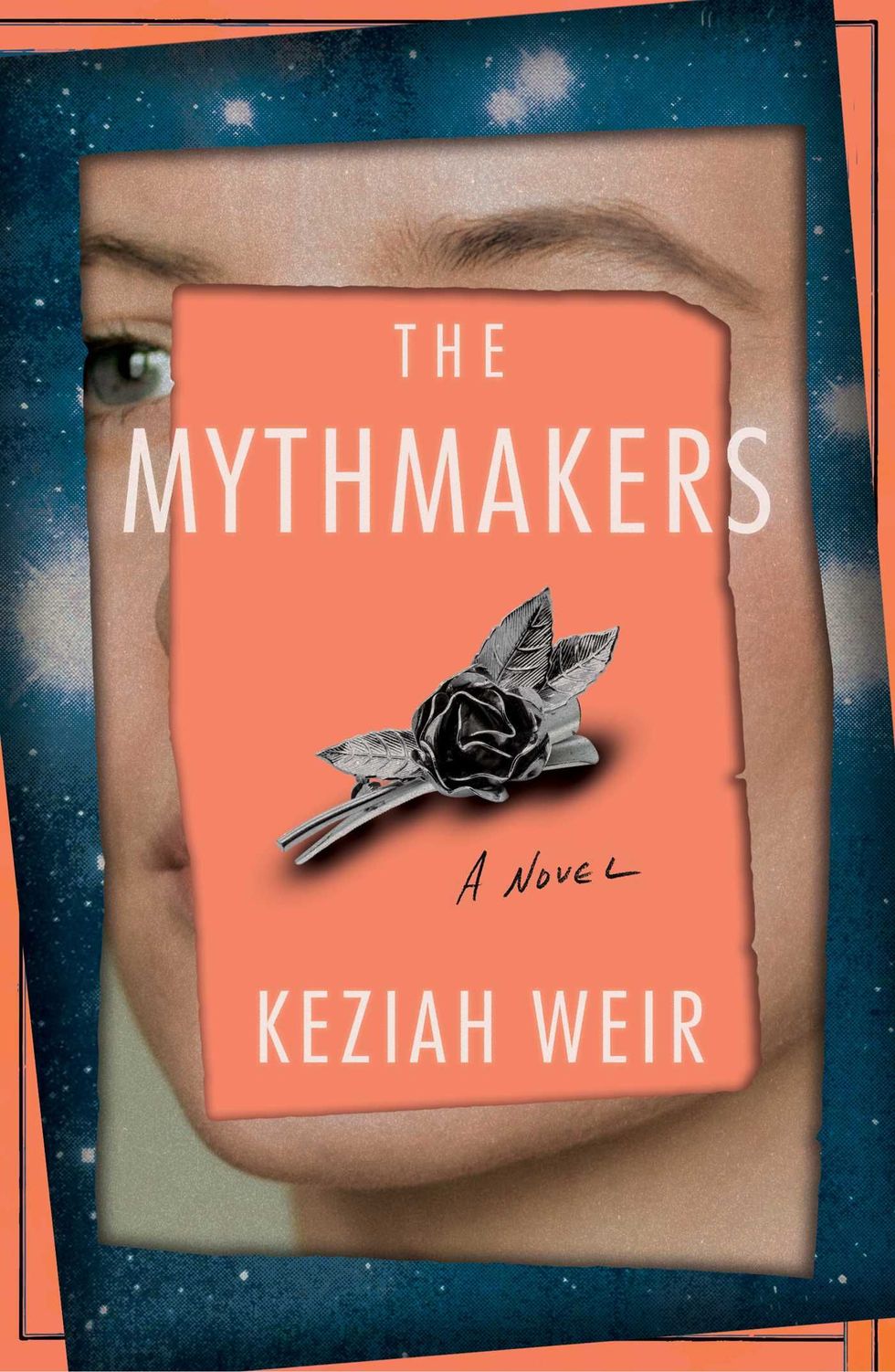

Vanity Fair editor Keziah Weir didn’t talk to anyone in the publishing industry while she was working on her debut novel, The Mythmakers. It’s understandable. After all, she was writing about their shared industry in a way that might make them pause. Weir’s novel follows Sal Cannon, a writer for a hot magazine and a happily partnered New Yorker. It’s tough to keep up with her life, but Sal is making it work. Until, that is, she loses her job due to some sloppy reporting and, potentially, her boyfriend to an even sloppier night out.

But Sal sees a lifeline in the form of a new story by a famous older writer that she thinks might be about her. The story recounts the night he and Sal met at a reading at the New York Public Library, and she thinks she can redeem her career with a rigorously reported investigation into the writer himself. When she finds out the story was published posthumously, Sal decides to continue with the investigation anyway by piecing the man together based on recollections from his friends and family. Informed by her experience as a journalist, Weir’s The Mythmakers is a poignant look at storytelling and the ownership of said stories.

Shondaland sat down with Weir to talk about journalism versus fiction, her experience in the magazine world, and getting duped by a subject you thought you knew.

SHELBI POLK: Where did this story come from?

KEZIAH WEIR: There were various aspects that had been percolating for a long time, as far back as stories that I was writing as an undergraduate. But I think the clearest germ of the novel sprung up when I attended a reading at the New York Public Library in 2014. I had a really wonderful undergrad fiction professor who was a big champion and mentor to a lot of his students. And sometimes when he was in the city, he would let me know about readings that he was attending. I was working as an editorial assistant at Elle, and I think he knew that I was wanting to be writing fiction but not finding the time or motivation amid having a day job and just being 21 and 22 in the playground that is New York. One [reading] that he invited me to was at the Coleman Center. It was a conversation between Karen Russell and Rivka Galchen. And it was incredibly wonderful and inspiring, and it made me want to go home and write. But after the reading, we went into the next room for the reception. This older man who was maybe in his 70s started talking to me, and he was very flattering. He made all kinds of pronouncements about my life. And at one point, he really did say, “Your life will only become more beautiful than it is now.” Then he left, and my professor came up to me and said, “Do you know who that was?” I had no idea, but it turned out that he was this cult screenwriter who had written this beloved cult classic ’80s science fiction movie. That stuck in my mind but also very quickly started morphing into the idea of “What if you’re at a point in your life when you’re searching for something, and you meet someone who has already done the thing that you’re wanting to do and tells you that all your dreams and desires are a possibility and maybe even an inevitability?” And then, for the next seven or eight years I worked on turning that into a bigger story, and it sort of spun out from there.

SP: I love that. That interaction felt extremely plausible.

KW: Yeah, that’s the only part of the book that is lifted from my life, but it is very much lifted.

SP: Especially given the power dynamics and the money in journalism right now, one poorly researched article knocking you out of a career really is every writer’s worst fear, isn’t it?

KW: Yes, very much. And I think around that time, there had been a few instances of writers being duped by subjects. And of course, there are instances of the writers doing the duping, but I think that was very much on my mind and an anxiety that I was holding.

SP: It seems like one of the questions you’re mulling over here is how does anybody decide who has ownership over a story? That seems very connected to your work as a writer. Where does that question pop up for you?

KW: Well, it’s funny. You know, I think there is a little bit to that truism that you can go back to your kindergarten self and see what you’re still interested in now. And even when I was little, I loved stories where the big reveal at the end is like, “The story that you’ve been hearing about the werewolf eating all of the townspeople is actually being told by the werewolf himself.” Then when I was in college, I was reading a lot of Philip Roth and Nabokov. And so much of their writing revolved around how to tell a story, who’s telling a story, and the fairness or unfairness of that. And then I think, being in journalism and magazine journalism and starting to tell other people’s stories, I think just increasingly you realize what a difficult practice that is and the responsibility of it. It takes the idea of “How can anyone really know somebody else?” to such an extreme level. How can anybody know anybody else after a few hours or even many sessions over a year? And how can you know someone enough to write them down? I love profile writing. I love reading them. But it’s such a complicated business. So, I think I’ve always thought about it, but as I started doing it myself, you just start thinking about it in different ways.

SP: We talk about the legacy of writers, especially dead male writers, all the time. The Mythmakers is about the legacy of a dead male writer, but almost every single voice in this story was a woman. Tell me about the choice to contextualize it like that.

KW: For a really long time, the writers who I admired so much were men, and a lot of my literary and writing mentors were men. Then, I was working at this women’s magazine and starting to read a lot of contemporary fiction by these incredible women authors. A lot of the male authors who I was reading, who I really admired, whose books I adore, write women in interesting ways and sometimes have big blind spots. So, I thought, maybe there can be a young woman writer who’s very entrenched in the white male canon who then starts thinking about that for the first time. I think that Sal, she’s maybe like a bit of a late bloomer in certain ways, which I also identify with. And she is just starting to think about what it means to be trying to do something that for so long has been dominated by white men.

SP: It’s hard to think critically when everything’s going well for you.

KW: Yes, yes, exactly.

SP: You just don’t even know what you don’t know.

KW: Which I am reminded of every day.

SP: Curiosity as a discipline felt like a big piece of your story too. You do have to keep asking questions to get to the story behind the story.

KW: Right, right. And sometimes you don’t even know what questions to ask. I think curiosity, that’s very much an idea that’s important to the story. And lack of curiosity and how that can blind you to things and cut you off from people.

SP: Have you ever gotten duped by a subject like Sal did in the book?

KW: Yes, I will be very careful. … I wrote a short piece about the author A.J. Finn for The New York Times. And then a year later, The New Yorker published a long exposé about A.J. Finn. His pen name is A.J. Finn. His name is Daniel Mallory. And maybe that’s enough.

SP: Yep, absolutely. I remember all of that.

KW: And what’s interesting is that that happened well into writing the book. Of course, that experience did inform certain aspects.

SP: It’s hard to know as a news consumer what’s a mistake and what is bad faith these days.

KW: Yes, exactly. And the thing is, any time you talk to anybody, especially when it’s celebrities or people who are really heavily in the public eye, they are often lying to the person who’s talking to them. They’re saying they’re not dating the person who they’re dating. People can withhold whatever they want to when they’re talking to somebody who’s going to be telling their stories. So, I think there are different grades to that.

SP: I would love to hear about the difference in writing when it comes to fiction versus nonfiction. It looks like you’ve been doing fiction alongside a journalism career the whole time.

KW: I started working at magazines in 2013. And I started this book a year later, and I was also writing stories throughout. So, I think it’s a really nice balance. When I’m working at magazines, it’s not like I’m just sitting around writing long-form projects all day. I do a lot of other things. And so, sneaking in an hour or two at 6 a.m. to just work on fiction. Anything that I’m writing or editing for the magazine, the ultimate aim is that it will be read by other people and pretty soon. Writing fiction, especially when I was writing this book because it was the first, you can sort of live in the illusion or the delusion that you’re just doing it for yourself. For so many years, I was just alone with the book, which felt really fun. And it felt like the stakes were high, but I kept them purposefully low by not telling anybody other than my husband and close friends that I was working on it for a really long time. And that was really nice.

And then, it’s just a different mechanism when you’re getting to make up everything. But it is funny what parts of the book I would get stuck on because I’d want some weather pattern to be happening. And then I would go back and look at the year and the date and think, “Oh, it wasn’t raining on that day.” And then I realized that you could make it up! It was raining on that day because it’s fiction. But for a long time, that book was very true to the moon cycle and weather patterns. In some ways, because I do so much nonfiction writing, it’s helpful to ground the fiction in certain realities. But it is really nice to be able to just diverge in a way that you could never do when you’re writing nonfiction.

SP: How does it feel to be on the other side of the interview process? That has to be weird.

KW: It’s, honestly, extremely terrifying. I’m in general a pretty anxious person. And I don’t tend to get hugely anxious before I interview people at this point because I feel so prepared for it. But definitely relinquishing control, being on the other side, and going into it having no idea where the conversation will go is an interesting new perspective to be inhabiting. And everybody who I have talked to about this says, “But you’ve been doing this, so you’ll know the kinds of questions coming!” I have no idea what people think of this book! I have absolutely no objective understanding of how this book is going to be received. I can’t begin to guess what I’m going to say about it.

SP: It’s almost like the difference between writing fiction and nonfiction. I get to sit here with my scaffolding of questions and my understanding of exactly how many words are going to end up on the page.

KW: Yeah. And that’s part of what I was trying to do with the book, just trying to empathize or imagine what it’s like to be on the other side. And I think the various characters that Sal encounters or seeks out react differently to being interviewed. There are some people who just love to tell their story and have been waiting for a long time for somebody to ask them to tell their story. And then there are other people who are very content to just be seen for the work that they’re doing and not have further comments than that. So, that was fun to work with different characters who feel differently about that.

Shelbi Polk is a Durham, North Carolina, based writer who just might read too much. Find her online at @shelbipolk on Twitter.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY