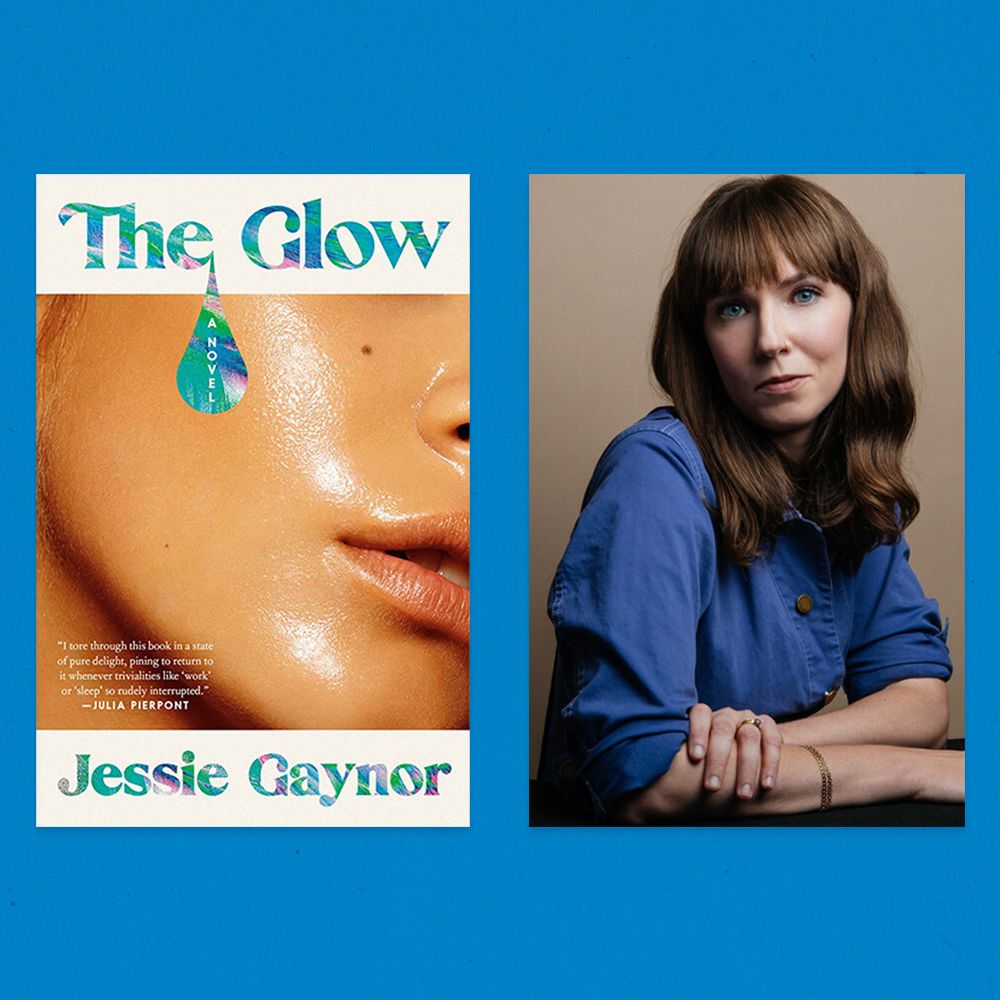

Living in a society where even our basic needs are treated like a commodity, it’s hard not to be influenced by companies seeking to exploit both people’s needs and insecurities. Who hasn’t fallen prey to a targeted ad promoting a hundred-dollar product that claims it will give your skin a youthful, dewy glow or a $60 bottle of pills that will turn your hair into an even more illustrious Rapunzel? No one is a stranger to this type of influence, and neither is debut author Jessie Gaynor. So, she crafted a whole novel examining the predilections of this elite group pushing these very products.

In Gaynor’s first novel, The Glow, we are introduced to Jane Dorner, a PR assistant who is drowning in debt, suffering through a breakup, and is on the verge of losing her job. Her saving grace comes in the form of FortPath, a wellness retreat with a jaw-dropping beauty, Cass, acting as its face. Jane views Cass and her partner, Tom, as nothing more than an opportunity to save herself from poverty, but sooner than she realizes, she gets wrapped up in the world and philosophy of the influencer entirely.

A senior editor at LitHub, Gaynor is also a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her work has been featured in WSJ Magazine, The New Yorker, and McSweeney’s. She spoke with Shondaland about the farce of wellness, how influencing can be akin to leading cults, and the importance of laughing through heartbreak.

CHANNLER TWYMAN: How did your own experiences with beauty and influencer culture inspire the creation of this book?

JESSIE GAYNOR: The most interesting and enviable thing about influencers is just how certain they seem about things. I recently read an interview with Alison Roman where she was like, “And obviously, I nap naked,” and it’s so wild to me that you can be so sure of a thing you do. Whenever I recommend something to someone, I feel like I have to qualify it 80 different times: “I like this, but you might not like it. I don’t know, you know? This is just the kind of food I like. I’m not saying my experience is universal but …” Meanwhile, influencers are just like, “This is the thing you must do, and it will work for you, and it’s just great.”

I really envy that complete certainty because that is not something I feel often in my life, and Jane — similar to me — struggles with uncertainty and what her path should be. I think there’s something really alluring about a person who says, “If you live this way, your life will be better.” I don’t want to say that influencers are religious figures, but I do think that’s something they have in common with them because that’s what’s also alluring about religion: someone telling you how to live.

The one-sentence germination of this project was “What if someone really wanted to join a cult?” Because they wanted to cede control of their decisions and have someone tell them what to do.

CT: Why the emphasis on beauty and wellness specifically?

JG: Beauty is me constantly trying to figure out what thing I can put on my face that makes me look like I haven’t lived for 37 years. In the influencer space, people are constantly saying, “Here is the thing that will work for you.” I’m not apt to believe in a lot of things, but skincare I will.

As far as wellness goes, something to me that’s interesting about wellness is that I’m Type 1 diabetic, and Type 1 diabetes is an interesting disease in that if you have access to insulin, you can live a pretty normal life, and if you don’t, you’ll die within weeks. It’s a disease that no one is trying to say they can cure with more “wellnessy” cures. Even with cancer, people will say, “Just drink this tea.” With Type 1 diabetes, everyone is on the same page that insulin is the only way to cure it. I feel like that has made me unsusceptible to wellness speak because those things can’t do anything for me; I just need insulin.

CT: Can you talk about the research that went into crafting the context of the novel? What are some things that surprised you?

JG: I worked at a space where I was doing affiliate marketing, like “100 Things You Should Buy on Amazon,” because I got a lot of PR. I didn’t want to denigrate that work, but I did want to show how silly the language around selling wellness can be. I wanted to differentiate selling wellness through a PR perspective and Cass’ perspective. Wellness-wise, it was a lot of Instagram and a lot of Reddit. I do have a ton of friends who are way more into wellness than I am. I talked to them about why they feel so sure about the products and activities they swear by. When I started writing the novel, I wanted Cass to be a little more dishonest, but later I found it far more interesting to write about a person who honestly believes in something. That was a turning point in writing it. I just think a lot of influencers really believe in themselves. Looking at that motivation is much more interesting to me than someone looking to trick people and make money.

CT: What about Jane’s character made it important for you to station the narrative through her POV?

JG: I love an unlikable protagonist. I think of myself as an unlikable protagonist sometimes. I’m not like Jane, but it was liberating to give voice to something about the unlikable things about me and put them in Jane and then amp them up. The idea of acknowledging the privilege of those around you but not your own is very internet culture in a nutshell. I think she’s someone that would love to watch a Twitter pile-on, but the moment that someone questions something she said, she’d crumble. I think that’s human, but it is something we should examine within ourselves. I do think it’s more fun to write the more villainous parts of people.

I actually found it more humorous to write in her perspective. In the first draft, I had written half of it through Tom’s POV, which was really interesting to write and definitely less barbed and funny, and Jane was such a great conduit for humor. All of my favorite books have a lot of humor in them. That’s what I want to read and write too.

CT: What does Cass’ character represent? She’s such a presence in the novel, at least in Jane’s eyes, but it seems like she goes through life generally having everything handed to her. What were you trying to say about influencers, and how so many of us desperately feel the need to be influenced by them, when their so-called magnetism boils down to superficial traits (in Cass’ case, her beauty)?

JG: I’m always trying to talk to people about “hot privilege.” Sometimes you’ll meet a person and think that they’re so interesting, and you’ll think it’s strange how you found them so interesting, and then you realize that it was because they were really attractive. If a less-attractive person had unusual interests, I’d think they were weird.

It’s interesting for a reader who can’t see Cass to be like, “What’s the appeal?” But it is interesting to think about how willing you’d be to give someone the benefit of the doubt when they say something interesting or wise or say something unexpectedly intelligent, all because of how they look. You don’t expect someone to be beautiful and intelligent. They have a leg up in your mind. Creating a character that wasn’t attractive wouldn’t have worked because no one would want to talk to them. We don’t think about how someone’s physical appearance influences our opinion of them.

CT: Tom seems to be one of the first to be influenced by Cass, so much so that he marries her despite their minimal sexual and intimate connection. How does their relationship set the precedence for Cass’ relationship with her followers?

JG: Cass’ relationship with Tom is where I did want to humanize her and show that she is someone who genuinely cares about people. I wanted her relationship with Tom to be rooted in something that’s real. Tom didn’t have warmth in his home, and Cass is the one who encourages him to be honest about his sexuality, whereas his family would rather deny it and not talk about it. Marrying Cass is the only way he can be honest about being gay. In the moments of Tom and Cass as children, despite most of Cass’ allure being based on appearance, we see a seed of her genuine ability to read people and tell them what they need to hear.

There is also something gross — though I hope it’s less prevalent now, despite it still being present — about Cass taking advantage of Tom in a way that shows she doesn’t see him as a whole sexual person.

CT: What is “the glow” that attendees of Cass’ retreat get by the time they leave? Is it imagined, metaphorical, or physically tangible? What does it represent as far as the story is concerned?

JG: Some things about wellness are true. If you drink more water, you probably will feel better, and the same with vegetables, but it’s not magic. It’s not sustainable for most people. If you are rich enough to be able to eat carefully prepared meals of all vegetables, or not have to sit in front of the screen, or work in the sun, or do a lot of tasks that are necessary for people who do not have a small army attending to them, you probably will look and feel amazing. That’s the privilege.

If I had Tom as my chef and I could do yoga for three hours a day, I’d probably glow, but I have to work and take care of kids, so I throw a handful of cashews in my mouth. “Glow” is the [word] used when describing skincare. It’s also something that can reflect on other people. A glow invites people in. It’s something that can be shared. A lot of the language around wellness is about sharing and inclusion, when in fact, it is pretty solitary. It’s about oneself — very autonomous. So, the false promise of a glow being something that can be shared is what drew me to that word specifically.

CT: There are parts in the novel that are tough to read, but there are others that had me in hysterics! Tell me about the process of writing this novel with so much humor despite its characters rebounding from so much suffering.

JG: Some of my favorite books are those that tackle darker themes with humor, and that’s how I deal with bad s--t in my own life. My mom has Parkinson’s, and joking about it with my siblings has helped us all cope. Joking is often seen as a deflection, but I actually think it’s a way to sit with something. When you’re laughing about something, you’re in it. Humor is so much a part of how I deal with the world, and it just made sense to put it in these characters. Even in the midst of something terrible, I think about how absurd it’s going to seem later. I don’t think that’s me trying to minimize it, but doing my best to sit with it.

CT: Is there anything else you’d like to share about your book?

JG: I’m genuinely so grateful to those who take the time to read this book. I used to hate when celebrities would say things like, “Winning an award is humbling,” but I do think there’s something to be said about people taking time to read this because it makes me think about how much else there is to be doing and reading, and I want to thank anyone who reads my book. I know it sounds cheesy, but I’m feeling very cheesy these days.

Channler Twyman is an emerging queer writer from Atlanta, Georgia. He has been published both online and in print through various publishers, journals, and creative sites and was recently named a Tin House YA Scholar.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY