Before entering the world of Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story, viewers should be aware that there is one obvious difference between that of the series that it will prequel, Bridgerton: the time period. Queen Charlotte takes place 40 years before the events of Bridgerton, when Charlotte is 17 years old and George is a new king learning how to rule his nation. As such, we’re no longer in Bridgerton’s Regency era — we’ve now entered what was historically known as the Georgian era of English history.

Because Bridgerton is a modern take on the Regency period, historian and Regency expert Hannah Greig was brought in to consult and ensure that key details for everything from the dress to the balls to the inner workings of society felt accurate. For Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story, creator Shonda Rhimes turned to Georgian royalty expert Polly Putnam. Putnam has worked for Historic Royal Palaces since 2012 as the collections curator and is also the King George and Queen Charlotte expert at Kew Palace, retelling the royal couple’s story on a near-daily basis to visitors. Such credentials were incredibly useful when building the Queen Charlotte world, but Putnam always knew that Rhimes wasn’t seeking to create an accurate historical drama. Even so, if the story isn’t period perfect, it’s no less useful historically.

“You accept as a historian that you’re in a wonderful fantasyland, but you also want to prevent things which people will pick up on that are obviously wrong,” says Putnam. “There are, of course, differing things to actual history, things like the timeline of the show that are slightly different to the timeline in history. And you just have to accept that as a historical adviser on a show like Queen Charlotte.”

Putnam worked with Rhimes to provide historical context for King George III and Queen Charlotte, their children, and George’s mother, Princess Augusta, giving direction and details of the intimate royal history of this family so that Rhimes could spin it all into the tale that is Queen Charlotte, which chronicles how the young queen ascended to the throne and, once atop the monarchy, found herself in a marriage that was as much a love story as it was a union that changed society forever. “Clearly, Shonda’s become such a fan of the history itself, and she’s doing her Shonda magic all over it to create a really great story,” Putnam says.

In the early stages of Rhimes’ scriptwriting, Putnam wrote detailed reports and full notes that served as a dossier of sorts as the story came together: “In her words,” Putnam says, “Shonda liked having a canon that she could work from and play off of. She’d done quite a lot of homework on George III beforehand, so for me, it was such a joy to [contribute].”

From both a historical and storytelling perspective, one facet of George III that Putnam feels is portrayed particularly well is the young king’s humble demeanor and also his interest in science and farming. It was during his reign that there was, spurred by industrial innovations of the time, a sea change in the urban and rural areas in the United Kingdom. As the population grew, more people flocked to cities from the countryside, and more mouths needed feeding, so agricultural improvement became top of mind not only for the country but also for King George, who wanted to make sure he could support his nation effectively and efficiently.

“For Shonda to pick up on the fact that the young George III was very interested in science and agriculture was a beautiful thing,” says Putnam, “because most other depictions of George are of him as a kind of sad, miserable, ill old man.”

But Putnam’s favorite note to Rhimes about George? She told her to feel free to do some topless, sexy farming scenes. Then, in the next script, there it was — some topless, sexy farming, which made Putnam quite happy.

“For me,” she adds, “the joy is that people will watch this and might want to come to Kew Palace to see the real history of George and Charlotte. We’re putting on a conference on the 18th-century Georgian era for another project that I’m doing, and one of the things that was really striking is that there are so few people of color doing 18th-century history. [These shows] are so important because I think it will get a better range of people to start studying this era, and that means we’ll get better and more interesting histories. I think that’s the real importance of it all.”

The history of the Georgian era

While we all know that Bridgerton, and Queen Charlotte by extension, are designed to be in a parallel universe to reality, there are some basic aspects that Putnam feels Queen Charlotte viewers might be interested to know about the Georgians.

The Georgian era is named after the Georgian kings. George I comes to reign in 1714, followed by George II in 1727. King George II’s eldest son and heir apparent, Frederick, marries Princess Augusta, but as it was a fraught marriage, Frederick treats his wife with much disdain and even hates their subsequent children, including the future King George III.

Luckily for Augusta, Frederick dies in 1751, possibly from pneumonia, or possibly from being hit in the chest by a cricket ball. C’est la vie, as they say. Frederick’s death has a profound effect on George III, who is about 13 years old at the time, and it’s at this moment when George III, the now future king, begins to feel the incredible pressure that he’ll endure throughout his reign to live up to his father’s legacy as a charismatic and strong-willed ruler.

King George III

After the death of her husband, Augusta hardens herself to court life. Before his death, Frederick had a large-scale political and personal fallout with his father, George II, and they were estranged for most of their adult lives. Political factions had formed around them both, however, with each boasting supporters and advisers. After Frederick dies, however, George II takes all of Augusta’s children from her to raise them in his house and under his tutelage. But Augusta, ever the clever and dedicated woman that she was, burns all of Frederick’s private political papers — guaranteeing that any incriminating documentation of Frederick or their marriage is destroyed — and then presents herself to King George II, literally falling upon her feet and pledging her loyalty to him. The king lets her keep her children, but the rest of Augusta’s life in the court — even after she was named regent of George III — isn’t without pressure. She is constantly surrounded by people like Lorde Bute, who was politically loyal to Frederick and his causes.

Less than a decade later, in 1760, King George II dies, and the pressure on George III as the new king to live up to his dead father begins to weigh on him mentally, with the inklings of a psychological decline being put in place.

King George III knows his father was a charismatic leader, but George III is written off as too simple and sensitive, which creates a larger rift between who he is and who he needs to be to become an effective leader — at least in the eyes of his mother and the court. For Putnam, this history, however simplified, helps to explain how and why George III had episodes of mental illness throughout his life that would eventually typify his rule in his older age. While there is debate among scholars, King George III is said to have died deaf, blind, and mad as a result of a metabolic disorder, porphyria; however, a hair sample was studied in 2005 and revealed that the king could have also suffered arsenic poisoning due to medicines and cosmetics.

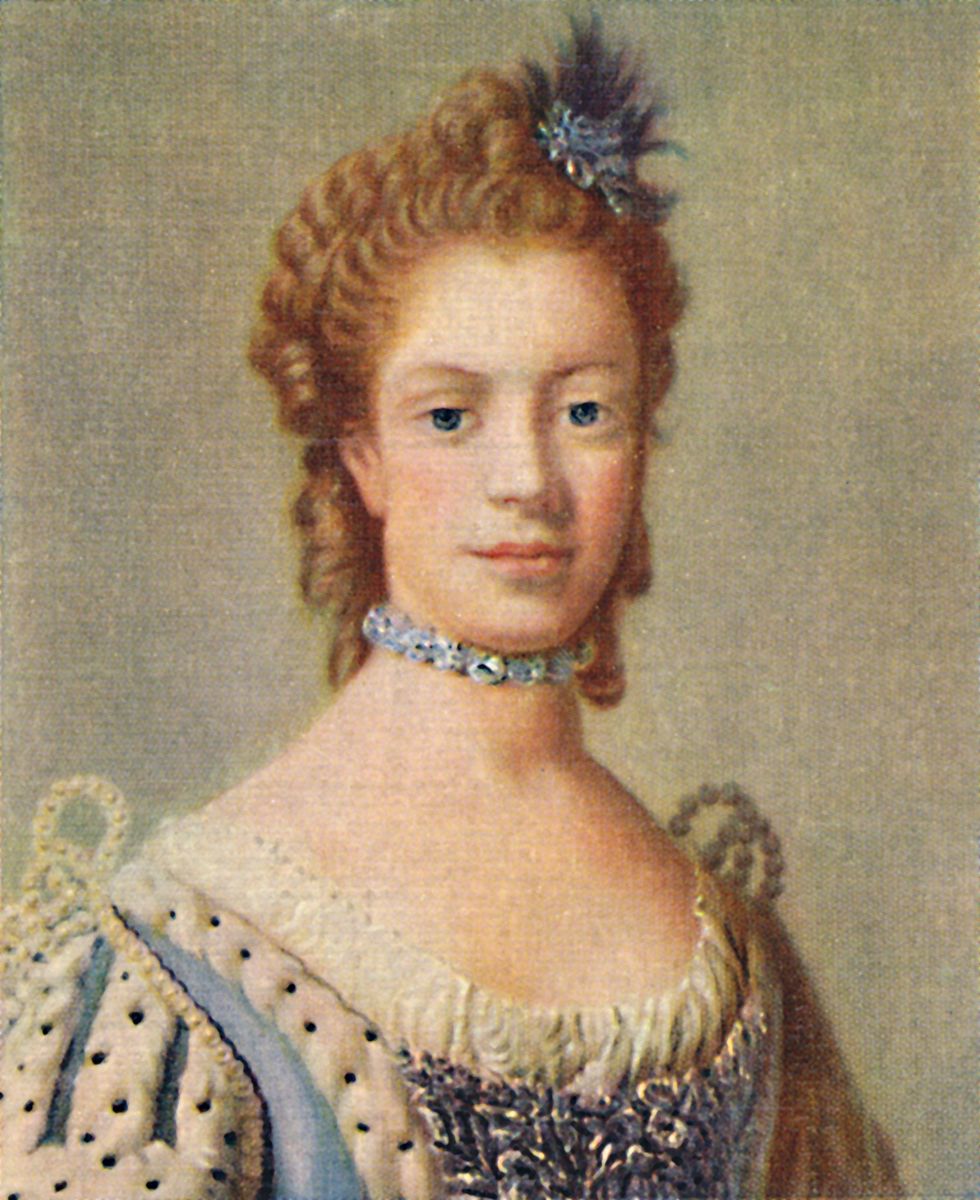

Queen Charlotte

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz was only 17 upon her betrothal to George III. She arrives — not of her own volition, it should be mentioned — from a rural estate in a minor German duchy and must come to terms very quickly with her imminent marriage to the king of one of the most powerful nations in the world.

In historical texts, Queen Charlotte’s portrayal is one that exemplified a woman who knew that in order for her to be excellent at her role, she had to give the appearance of being meek and mild, do what her husband told her, and be good with the 15 children she bore for him. But Putnam says that there are hints of her extreme cleverness, as well as her interest in science, botany, geology, and theology.

Of course, it isn’t appropriate for her to express any of this in any public way, but there is a historical note from Charlotte to her best friend and lady of the queen’s bedchamber, Lady Harcourt, which says that if women were afforded the same education as men, they could achieve the same things. It gives the hint that there’s more to Queen Charlotte than she could ever actually reveal, a notion Rhimes was happy to explore in Queen Charlotte.

Putnam adds, “In her portrayal in the show, Shonda has taken that glimmer that maybe there was something more to the kind, lovely queen who had 15 kids; what if Charlotte could’ve been the woman that she was quite capable of being?”

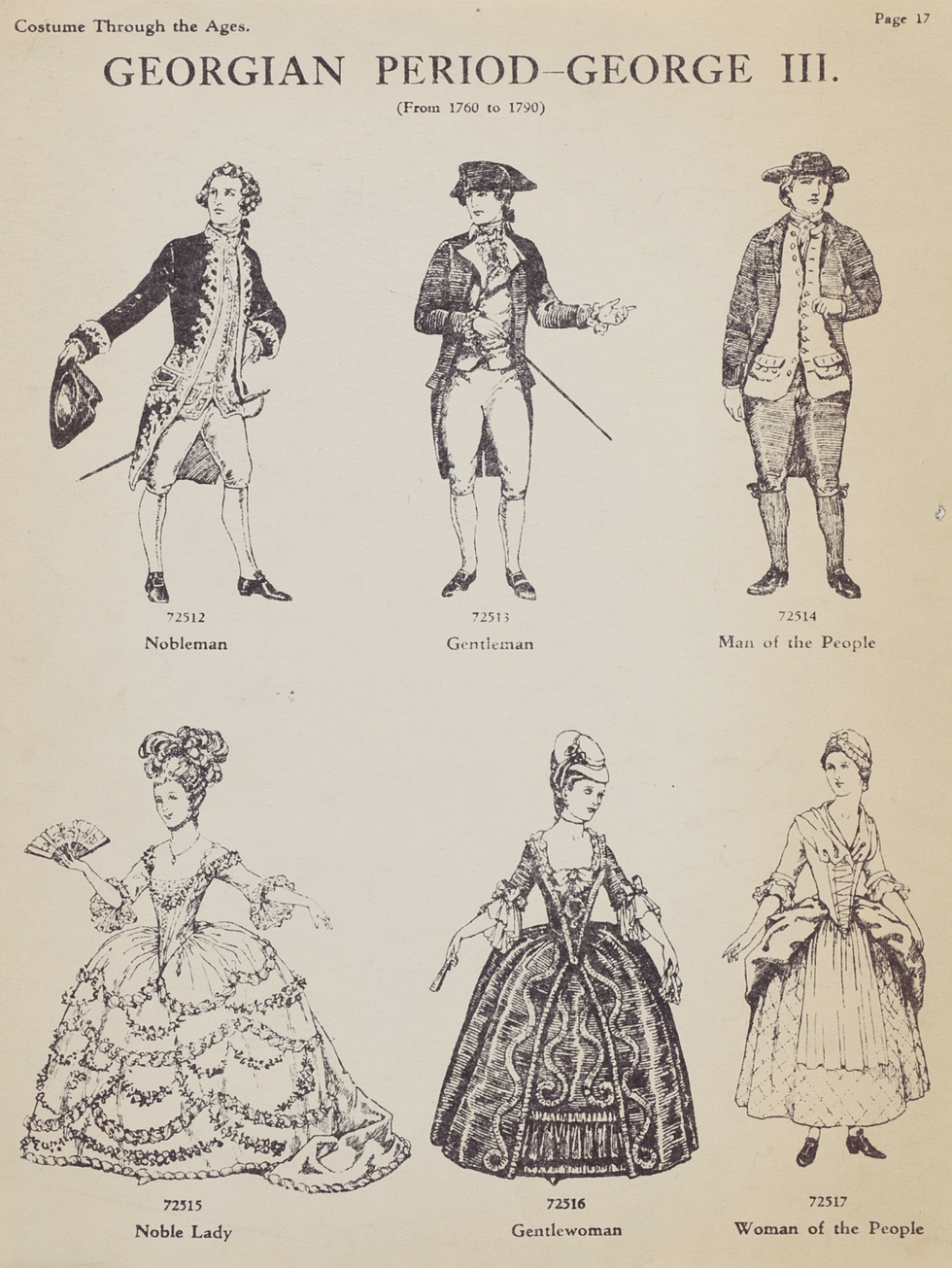

Fashion

The 1760s, which represents the first decade of George and Charlotte’s marriage, is probably the prettiest era of Georgian fashion, according to Putnam. As witty diplomat Lord Chesterfield said in 1745, “Dress is a very foolish thing, yet it is a very foolish thing for a man not to be well dressed.”

Costume designer Lyn Paolo dug into the Georgian era by reading Janice Hadlow’s 2014 masterpiece, The Strangest Family: The Private Lives of George III, Queen Charlotte and the Hanoverians. A long and fascinating read, it gave her and her team, including co-costume designer Laura Frecon, great insight into the royal family.

“I always start by looking at what was happening in the era,” says Paolo, who relished taking the historical and remaking it into a Shondaland fantasy. “We did intense research to understand the silhouette, the jewelry, and all this information about what they really wore. We went to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; we found portraits of [the royal family] from all over England. We went to a few museums in Spain. And we knew exactly what they did in 1761, and then we translated it to the world that [Bridgerton costume designer] Ellen Mirojnick created for Bridgerton.”

For women, corsets sucked in torsos and plumped up breasts, while wide hoop skirts disguised everything else underneath. Sleeves were three-quarters length, accompanied by cuffs often made of acres of frothy lace. Dresses were embellished with ruffles, floral braids, and ribbons — Georgians loved bows too. If silks were not plain, they were decorated with trailing patterns of lace and flowers.

When it came to the gowns, you wouldn’t be caught dead at a royal palace event or a ball without the widest of wide skirts. The more volume, the better — given how expensive fabric was, it exemplified your wealth while also making a statement on the greatest stage for sartorial display. In fact, it was in the 1760s that the notion of a fashion press developed. Like a red carpet today strewn with photographers, journalists would wait outside of palaces and stately homes to catch a glimpse of the glamorous attendees to report on what they wore.

Men were just as glamorous, says Putnam. Suits were made of embroidered silk and velvet in a wide variety of colors. Pink was a popular choice because, at the time, it represented virility. Men also wore jeweled cufflinks, jeweled pins, brooches, buttons, and buckles to embellish their outfits like women did.

“One aspect about this period that we weren’t so rigid about on the show was the women’s corsets,” says Paolo. “These women in whalebone corsets, they could hardly breathe. Their bodies were [molded] — corseted to train them to have that narrow waist — from a very young age.”

When Queen Charlotte dies in 1818, court fashions change. The wide hoop skirts with cinched mid-waists had already fallen out of fashion about 20 years earlier, but Charlotte preferred them and made it a stipulation for women to wear them in court. George IV, upon his rule, was known to be a spendthrift, but he also had loads of female friends and realized that they didn’t want to wear those big hoops anymore. That’s when the column silhouette and empire-line dresses we know so well from Bridgerton came into play.

Hair and makeup

Queen Charlotte hair and makeup designer Nichola Collins tells of a funny caricature print from the Georgian era where a young urchin boy reaches in through the back window of a horse-drawn carriage to grab the wig off some aristocrat. Aside from making her laugh, she says the depiction is perfectly indicative of how important hair was during that time.

“Everybody wore wigs,” says Collins. “No matter what area in society you were, you had a wig on your head. And if you couldn’t afford one, then you stole one. The higher, the better; the bigger, the better. With all the trimmings.”

Spanish and French royalty, namely Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, helped usher this hairstyle in to England and influenced an entire generation of British royals and their subjects. It was decadent, it was flashy, it was large-scale, and, like the dress, was a show of wealth because, of course, it cost a fortune to have the wigs made and maintained. One royal woman might have hundreds of wigs — one for each outfit, essentially. They’d also have wig dressers, all male at that time, tasked with keeping the wigs — usually made with horse, badger, or yak hair, and the most expensive made from human hair — in tip-top shape, including cleaning them of lice and fleas.

“This is not our world,” Collins assures, referring to the show. “Our world is beautiful. But the reality was that they’d have to be cleaned and kept hygienic; they’d be maned and repaired and then restyled. It was an endless job.”

And as fanciful as women’s hairstyles were, men’s were just as lavish. Since baldness was not in fashion, the only way to cover those patches was with wigs.

Collins’ first step in researching any period hair is to turn to the Richard Corson book Fashions in Hair: The First Five Thousand Years. Originally published in 1970 and now in its 16th edition, the text contains incredibly in-depth details of hairstyles from each decade, from ancient Egypt to today, for both men and women. It helps Collins not only to home in on a particular era but to also give context to the adjacent periods.

“No period [of fashion] just comes out of the blue,” says Collins. “There’s always cause and effect.”

After Corson’s book, Collins and her team use internet libraries, though she’s careful to parse through the overload of misinformation and will always turn back to the books for verification. They scroll through any site from which they can get images, including Pinterest. With Queen Charlotte, they were even looking for images that didn’t exist in the mainstream imagery archives because they hadn’t been represented. For that, they looked through family histories and diaries that could lead to any information that might be helpful. Collins also relies on the knowledge and references of Paolo’s research in costume design and production designer David Ingram’s work as well.

Makeup during the Georgian era was all about smooth, delicate, and powdered skin. Though for Queen Charlotte, Collins’ team never wanted to pale anyone down, so powder was not a part of her design. Instead, she represented flawless skin by accentuating each character’s natural skin tone.

In addition to powder, Georgians loved definition. Coal-based mascara and eyeliner were popular, and defined eyebrows were in. Women would supplement a skinny or thin brow with mouse hair — “Talk about microblading your eyes with a mouse!” says Collins. Another standout style was blush on the cheeks. They’d use any type of pigment from a plant, fruit, or vegetable mixed with an oil and would apply it on the apples of their cheeks and slightly below, where one would naturally flush. All in all, the Georgians loved makeup, and both men and women would have some sort of facial routine to go along with their dozens of wigs.

“It’s good to have a deep understanding of what led up to this period and where these fashions came from,” says Collins, “but we chose our own interpretation of the period. We were creating for character, for the actor, going into small details of the story. Who are they? What is their role? Where are they in society? Where did they come from, and what’s their journey?”

For the answers to these questions and so much more, be sure to watch Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story, premiering Thursday, May 4, 2023, on Netflix.

Valentina Valentini is a London-based entertainment, travel, and food writer and is also a senior contributor to Shondaland. Elsewhere, she has written for Vanity Fair, Vulture, Variety, Thrillist, Heated, and The Washington Post. Her personal essays can be read in the Los Angeles Times and Longreads, and her tangents and general complaints can be seen on Instagram at @ByValentinaV.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY